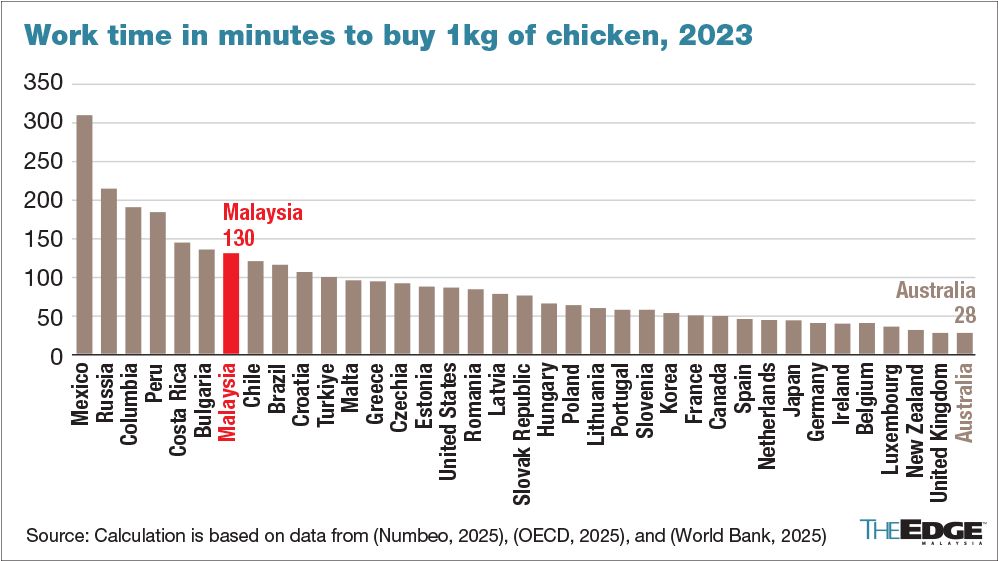

KUALA LUMPUR (March 11): A study by University Malaya’s Social Wellbeing Research Centre (SWRC) reveals that a minimum-wage worker in Malaysia must work four times longer than their Australian counterpart to afford 1kg of chicken.

The working paper entitled Food Affordability in Malaysia: When Markets and Money Decide What to Eat found that a minimum wage earner needs to labour more than two hours or 130 minutes to afford 1kg of chicken, while in Australia, it takes only 28 minutes.

The report states that Malaysia's minimum wage was below US$500 (RM2,207.40) in 2023 while Australia's minimum wage was close to US$2,500.

“Food affordability in Malaysia is increasingly shaped by urbanisation, wage structures and market dynamics. With nearly 80% of Malaysians now residing in urban areas, access to food is no longer determined by availability but by affordability,” the study said.

Authored by visiting expert social security economist Dr Amjad Rabi and SWRC director Professor Datuk Norma Mansor, the report found that despite food prices being lower than the global average in Malaysia, income inequality and low wages continue to restrict access to essential nutrition for a significant portion of the population.

According to the World Bank, Malaysia’s food price level stands at 83.08% of the world average, indicating that food remains relatively inexpensive compared to global standards.

International comparisons, however, highlight Malaysia’s income challenge — minimum wages that are lower than those of peer countries.

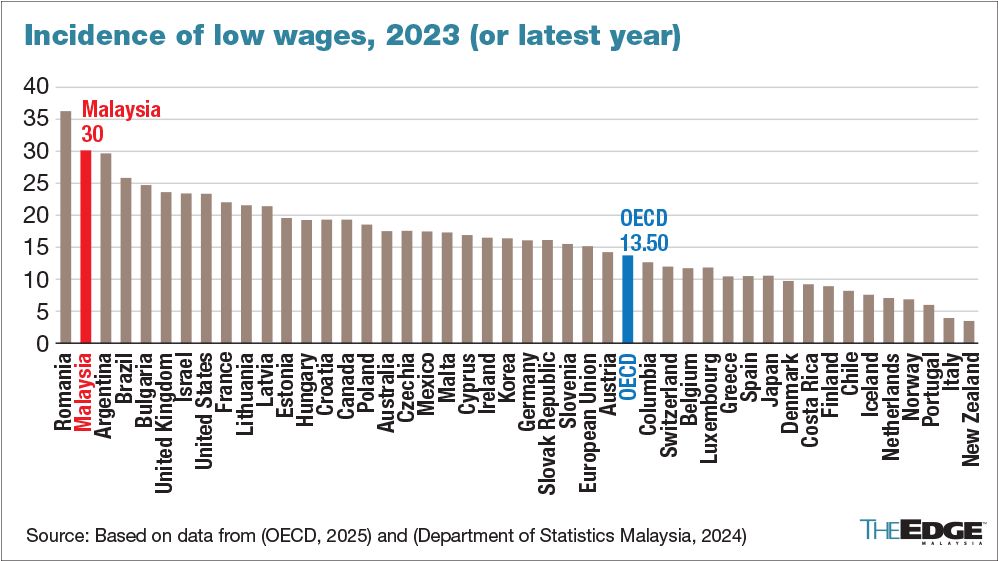

In Malaysia, a large portion of the workforce earns low wages, with over 30% of workers earning less than two-thirds of the median wage, more than double the 14% rate seen in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

This widespread issue of low pay, both in absolute terms and the number of affected workers, exacerbates financial strain and limits many households' ability to consistently afford a nutritious diet.

This affordability gap forces many households to turn to cheaper, calorie-dense foods like instant noodles and fried foods.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation, such dietary shifts contribute to rising rates of malnutrition, including both undernutrition and obesity, particularly among low-income urban populations with limited access to fresh, healthy food.

The study proposes three key policy interventions to improve the purchasing power of low-income households: a comprehensive social protection floor, expanding and strengthening the school feeding programme, and implementing automatic minimum wage adjustments.

1. A comprehensive social protection floor

A comprehensive social protection floor is essential for ensuring income security and food affordability, particularly at critical stages of vulnerability such as childhood, old age, unemployment and disability.

In Malaysia, gaps in social protection leave many, especially in the informal sector or low-wage jobs, without financial security.

The report said strengthening child benefits and income support for the elderly and disabled can help prevent food insecurity during economic hardship.

Adopting a life-cycle approach can reduce poverty and improve health and development, particularly for children and the elderly, who are most vulnerable to nutritional deficiencies and economic instability.

2. Expanding and strengthening the school feeding programme

Malaysia's school feeding programmes are limited in coverage and quality, according to the study.

Expanding access to all primary and secondary students, especially in low-income areas, would improve nutrition and economic security for vulnerable households.

International evidence shows that well-designed school feeding programmes lead to better education, employment outcomes and public health.

3. Automatic minimum wage adjustments

Malaysia's minimum wage system lacks an automatic adjustment mechanism, leading to stagnant wages that don’t keep up with inflation, eroding the purchasing power of low-wage workers.

Although the government raised the minimum wage to RM1,500 in 2023 and plans to increase it to RM1,700 for all workers by July 2025, these adjustments are sporadic and reactive.

The study recommends introducing an automatic adjustment mechanism, linking the minimum wage to two-thirds of the median wage, similar to systems in countries like France, the Netherlands and Poland.

This would ensure wages keep pace with living costs, improve income stability, reduce reliance on unhealthy food options and help alleviate food insecurity, benefiting both urban and rural populations.

- China warns nations not to cut US trade deals at its expense

- Three banks underwrite the entire retail portion of Main Market-bound Paradigm REIT

- Crude palm oil's discount to soybean likely until 3Q, may spur Indian demand — analysts

- Taiwan's TSMC warns of limits of ability to keep its AI chips from China

- RHB IB turns bearish on Malaysian banks amid tariff worries and slowing growth

- Four Pan Borneo Sabah Phase 1A packages completed — Nanta

- NEWS: ACE Market-bound PEOPLElogy in M&A talks

- China-owned supertankers face US$5.2m in fees per US call

- US investor Cameron offers US$5 bil for Kazakh mining giant ERG, letter shows

- Pulau Kapas Ventures distributes 15% Time stake to Khazanah, Global Transit International