This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 10, 2025 - March 16, 2025

AHMAD Zulqarnain Onn, CEO of the Employees Provident Fund, smiles when asked whether he will be celebrating his first full year at Malaysia’s largest institutional fund with 6% dividends for its 16.2 million members, of which 8.8 million are still actively contributing.

When met at EPF’s headquarters in Kwasa Damansara, the 2024 dividend of 6.3% had yet to be announced. “It takes a little bit of time [from year-end] because it is a very complex portfolio, and data has to come in from external managers. There is also the process of fair valuing the assets and making sure any necessary impairments are done. We do it on a judicious basis ... so, even if I wanted to tell you, I cannot [just yet],” says Ahmad Zulqarnain, who was president and group CEO of Permodalan Nasional Bhd (PNB) before taking the helm at EPF on Feb 19, 2024, succeeding Datuk Seri Amir Hamzah Azizan, now Finance Minister II.

In the absence of pandemic-related special withdrawals, which saw more than RM145 billion prematurely taken out from the statutory retirement kitty and resulted in rare net outflows from the provident fund in 2021 and 2022, EPF is seeing some RM4 billion in monthly net inflows in 2024.

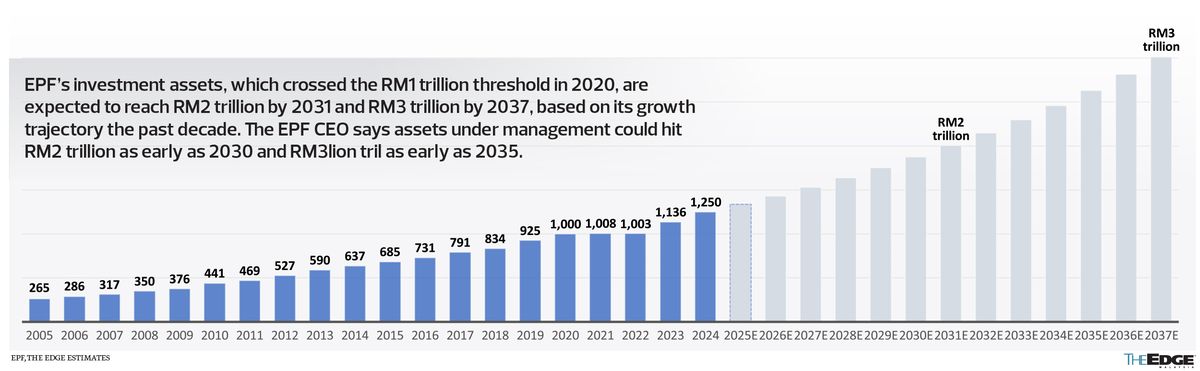

So, coupled with a strong financial performance, it is little wonder that EPF’s fund size, which crossed RM1 trillion in 2020, is set to double every 10 years. It is already the 13th largest pension fund in the world, and the fifth largest in Asia.

According to Ahmad Zulqarnain, 2024 was a “record year for inflows”, with gross contributions reaching RM118 billion, shored up by incentives such as i-Saraan to get non-salaried workers to also save for retirement with EPF and its people actively reaching out to get members and non-members to save more for their old age.

“Of the RM68 billion that came out, RM12 billion was from [Flexible] Account 3. Our original estimate for Account 3 was RM25 billion [44% of the RM57 billion that could have been withdrawn if every member aged below 55 opted in by Aug 31, 2024] and the actual amount withdrawn for 2024 was RM12 billion; so, it’s around half,” he elaborates, noting that net inflows into EPF was around RM50 billion in 2024.

Citing the fact that 70%, or nine million members aged below 55, made no withdrawals from Flexible Account 3 — which allows for any-time withdrawals with no questions asked — Ahmad Zulqarnain reckons that more Malaysians are aware of the need to save for retirement and the power of compounding interest with EPF.

“We’re quite happy that it is only about half of what we expected… the next question is, how come it was lower? Generally, the economy was strong in 2024 … Bursa Malaysia also performed well in 2024; so, a rising tide lifts many ships,” he says.

That 75% of statutory contributions are locked up in Retirement Account 1, as opposed to only 70% before the introduction of Account 3, Ahmad Zulqarnain says it is still a small win towards better retirement.

He concedes, however, that more reforms need to happen faster to ensure more Malaysians have a better chance at a dignified retirement.

Without sharing confidential information, Ahmad Zulqarnain says “there is definitely movement in government about [putting] ageing high up on the agenda” in the 13th Malaysia Plan (2026-2030) framework.

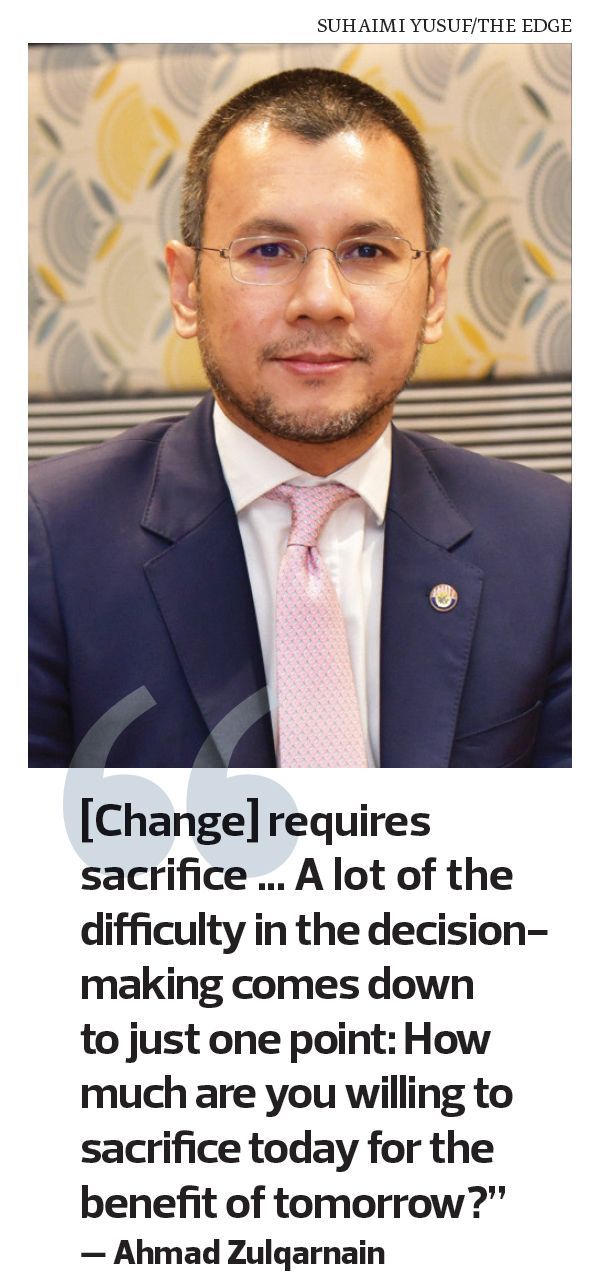

“We need to have a nationwide conversation on the things that we want to change, and are willing to change. Many of these changes, at the end of the day, require sacrifice. Pensions are very complex. I don’t want to diminish the complexity of pensions and the retirement policy … but a lot of the difficulty in the decision-making comes down to just one point: How much are you willing to sacrifice today for the benefit of tomorrow?” he says, calling for nationwide dialogue on necessary reforms for better retirement.

Ahmad Zulqarnain says EPF is a firm believer in its Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA). “We believe 80% of the returns that you get over a sustained period of time is derived from your asset allocation decision-making. And that is very consistent with how many large global pension funds operate as well. We take a lot of care in making sure we are at asset allocation at all points in time. And we also review the asset allocation every three years. So, 2025 is a fresh asset allocation … our investment panel is intimately involved in the process. That’s where the expected returns are discussed, the risk tolerances are discussed, what assets are available and not available for us or that we don’t want to invest in. All this is thrown into the mix to arrive at the SAA, and this rigour around asset allocation is what has been driving EPF’s returns for almost two decades,” he says, adding that the investment teams at EPF then do their best to find possible investments within each asset class.

The discipline is very important, given that EPF expects to grow its assets under management (AUM) about 8% per year for 20 to 30 years.

“Despite being an ageing nation, the mathematics or the demographics are such that we will continue to grow for long periods of time. If you’re growing at 8% [nett] per year, you are basically doubling your fund size every nine years. So, we anticipate that EPF will be a RM2 trillion fund by 2030 and a RM3 trillion fund by 2035; so, the growth is quite rapid. The challenge for us, despite being pretty good at delivering returns in the past, is that as the fund size gets bigger, [so does the need to increase] our level of efficiency and sophistication to also deal with a much more complex world. This is something we think very hard about.”

Asked about the Ministry of Finance-led GEAR-uP programme, where EPF is tasked to direct investments into high-growth, high-value industries such as AI and advanced manufacturing, Ahmad Zulqarnain assures members that EPF “remains asset allocation-driven” and will allocate capital only in areas that fit its investment parameters.

“Bear in mind, EPF is, has always been and will continue to be a relatively prudent investor. We are not going to throw that away, because that is the backbone of our success,” he says, noting that there are opportunities in Malaysia in areas such as infrastructure, including digital infrastructure such as data centres or mechanisms to facilitate the movement of data, as well as energy and energy transition.

While EPF works on growing members’ savings, Ahmad Zulqarnain says Malaysia needs to face up to the realities that come with a greying society. Below are excerpts from the interview.

The Edge: EPF is proof that policy for forced savings for retirement is necessary. Yet, it seems rather ironic that policymakers are legislating mandatory contributions for foreign workers instead of for Malaysian gig workers.

Ahmad Zulqarnain Onn: I don’t think ‘ironic’ is the word I will use. It’s a question of what is the timing for the introduction of these policies. These things are debatable, and they should be debated on what should come first.

Obviously, as the practitioner in the pension space, we want everything to come all at once. We have a whole checklist of what we would like to see happen and, ideally, everything is implemented immediately. But I don’t think that is practical [or] feasible, politically. And when I say politically, it is not so much whether politicians will make the right decisions; it’s also acceptance of the public, because politicians also react to what the public feels is right or wrong and what their own desires are. They are wakil rakyat. They’re representing the public.

Because it’s such an important topic, I do advocate that that conversation with the rakyat happens. It’s incredibly important, because the world has also changed, where maybe 50 years ago, it was very easy. Just [decide] everything top down. There are certain societies or countries where that’s easier than others. But society has also changed, and therefore we need to engage, we need to have town halls. Town halls shouldn’t be in companies, town halls should be in towns.

If you had a sequencing list or wish list for pension-related reforms, what would it be like?

High priority would be aligning the withdrawal age with the retirement age. It is only logical for it to be the same. If the retirement age changes, the withdrawal age also changes.

The best pension systems have streams of income over a long period of time. They also protect against longevity risk; so, you don’t have to worry about running out of money if you live to 95 or 99. And that will be sort of what is technically called an annuity, where, irrespective of how long you live, that is the stream of income you have. We don’t have that today.

Starting points matter in these things. We started off as a provident fund, similar to Singapore’s Central Provident Fund (CPF), similar to EPF in India. The commonality of this is, of course, it was set up by the British. And provident funds traditionally allow you to have lump-sum withdrawals, which we still allow. But over time, we do see these systems transitioning, because with experience, they realise that members tend to exhaust their funds very quickly, that they then change it into streams of income.

CPF has shifted over time, over two phases, where initially it was a certain portion of your savings that can be withdrawn on a schedule, not with a lump sum. Subsequently, they introduced something called CPF Life, which is the annuity. So, irrespective of how long you live, you get that stream.

Transitioning is not so easy but we have to figure out how we can transition. The easy way is you start with a new cohort. When we test with the public, starting with new cohorts, no one has any problems. And it’s quite interesting how psychology works. If you ask a typical parent, would you like this for your children? They will say: ‘Yes, I want my children to be protected for life. I want the streams of income.’

But asked whether they would like it for themselves — the exact same thing — and the same person would say ‘no’. And that, I think, illustrates the policy challenge that we have. You know that it is good for you, but just do it for my children, not for me.

Would giving a higher guaranteed return in the letter of the law from the current 2.5% [for conventional savings] make mandatory contributions more palatable?

I don’t think so, and I would not advocate for that because, number one, I wouldn’t want to increase the contingent liability of the government. It may seem invisible, but it is a contingent liability, and I think we can manage the fund in a way that we don’t need to increase that contingent liability.

There are other techniques available for us to be able to do this. If we introduce this for the next generation, what we call ‘income drawdown’, in the sense that a certain amount cannot be withdrawn lump sum but be drawn monthly, we will give the same option to others as well. And how we may then incentivise doing that is something [that is to be worked out].

Just as a general principle, the thing about Social Security or pensions, when you make it voluntary … voluntary is best with some matching incentive. That incentive could be in many different forms, similar to i-Saraan, where there’s a matching incentive that introduces people to try it and test it, and then we try to make it sticky so that it continues over time.

In 2018, EPF encouraged ride-sharing driver-partners to save for retirement via voluntary contribution. Singapore, however, passed legislation so that Grab has to make employers’ contributions to gig riders who also have to make their own contributions to CPF. Is that not an example of Malaysia losing out?

I don’t think it’s a competition [but] I think you will see these reforms come through. It’s a question of speed and timing. We are in engagement with policymakers about what we think the reforms [should be], the timing of those reforms and how it should take place.

Do you see mandatory contributions for gig workers happening this year or next year?

I think eventually it will happen. The ideal state is that all occupations, whether formal or informal, are covered. Countries that do it, tie it with tax. I’m simplifying a little bit. You are self-employed, an Instagram influencer making RM200,000 a year. The tax people know your income. When you file your taxes, you also pay your own contribution. That’s generally how it works. It’s quite different from salaried employees — where it’s just deducted — because [for the self-employed,] there’s no central point to deduct from. You have to use different mechanisms for the payment to happen; and to make sure that the payment happens just like tax, there are ramifications if you don’t pay tax and if you don’t contribute to your pension fund. But there is some complexity in it, and there’s a lot of inter-agency requirements, but the most important thing is there has to be public buy-in for this.

What other reforms should happen quickly?

Converting at least basic savings to an income stream is a high priority [as is] expanding coverage to informal or categories of workers who are not today contributing to EPF. It’s about expanding coverage from the 60% covered right now to a higher number, [and] making sure that when people retire, whatever they have saved goes a little bit longer, and eventually protecting them on longevity risk as well.

We are trying to push on financial literacy surrounding retirement adequacy as well, encouraging people not to withdraw, and encouraging people to save early to take advantage of the power of compounding, in particular. In Budget 2024, intergenerational transfers were announced, where parents with a little bit of extra money can transfer it to their children so that they then start to benefit from this compounding earlier as well.

At a recent EPF conference, several speakers said if savings are not forced, people just don’t save. Why do we still choose to be voluntary?

I think the forced-saving mechanism has been very beneficial not just for Malaysian society in general, but also the Malaysian economy in general, because it also forms a large part of the savings pool of the country. And this pot of savings eventually finds its way into the real economy through purchases of bonds, equity, real estate infrastructure and so on. That’s why, generally, Malaysia, especially in its early years, had a relatively high savings rate, because there was this forced-savings mechanism, and the World Bank and others have acknowledged that huge benefit that we have.

But you cannot underestimate the complexity once we move away from formal employment, and you cannot underestimate the enforcement that’s required if we make it mandatory. For example, if we made it mandatory for the pisang goreng seller who is self-employed and doesn’t currently contribute to EPF, are we going to enforce against that individual? That is a policy question that we need to think about. Right now, it’s very easy to enforce against a company’s board of directors that have these obligations. But when you move away from that, there are added complexities and societal issues that you need to think about.

EPF has tried to raise awareness on the importance of delaying withdrawals. Yet, public backlash against delaying withdrawals remains strong. One narrative is that EPF is asking to delay withdrawals because it ‘does not have money to give back to members’ rather than ‘ensuring financial security for longer, if not for life’. Is there a way to counter this narrative so that we can move forward?

We manage the portfolio in such a way that we always have liquidity. If you look at our asset allocation, more than 47% is in low-risk assets. A large part of that is highly liquid in the form of Malaysian government securities. So, there is really no issue surrounding EPF raising liquidity at any point in time. The issue really is about understanding. Every single debate around pensions boils down to this one simple question: ‘How much am I willing to give up today for the benefit of tomorrow?’ There is a lot of debate surrounding it, and rightfully so. I will be the first to advocate that any policy change should be debated robustly, but we should be very clear that it boils down to this one point.

If the pisang goreng seller or politician asks you, ‘Why should I decide to give away today for tomorrow?’, what would you say?

I will give the same answer I give to my children, that savings is a virtue. You must put away money for a rainy day and you must put away money for your future. The act of saving, in itself, is a virtue.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Making a bold move in Kota Kinabalu

- Ukraine to seek more US investments in talks over economic deal — Bloomberg

- Businessman with 'Tan Sri' title, said to be O&G industry veteran, arrested for RM10m scam

- Indonesian Muslims to celebrate Eid on Monday

- Myanmar hit by fresh 5.1 aftershock, tremors felt in neighbouring countries