This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on February 10, 2025 - February 16, 2025

PLEDGING the current administration’s commitment to achieving holistic growth that benefits every Malaysian, Minister of Economy Datuk Seri Rafizi Ramli last Wednesday (Feb 5) talked about how his working-class parents, who left school at 12, benefited from early state intervention. This support enabled him to receive quality education at a boarding school, broadening his perspective and opening his eyes to new possibilities for his future.

“Had I not had that opportunity, I would have been confined to the rural area, seeing only what my parents had seen. But early intervention — and the opportunities that came with it — allowed people like me of the previous generation to understand that you can escape [low income]. The challenge for this government is to extend the same opportunity [to others] in a much more challenging fiscal and economic situation,” Rafizi said in his opening address ahead of a panel discussion marking the official release of the latest World Bank report titled “A fresh take on reducing inequality and enhancing mobility in Malaysia”.

While Malaysia has reduced poverty and fostered success stories like that of Rafizi, 47, and Tan Sri Abdul Wahid Omar, 60, an accountant who was president and CEO of Maybank before being appointed Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department in charge of the Economic Planning Unit (2013 to 2016), findings in a World Bank report under discussion have raised questions about the effectiveness of Malaysia’s affirmative action policy — 55 years since the New Economic Policy (NEP) was introduced in 1970 to eradicate poverty and remove the identification of race with economic functions and geographical locations.

This was reflected in the top-voted question from the audience for the panel discussion, which was ultimately skipped because of time constraints.

“Even with the bumiputera affirmative action, the Malay group still has the biggest inequality? Is the bumiputera affirmative policy still relevant? The inequality between the rich and poor bumiputera is wide and stark. This policy has also had an impact on Malaysia’s economic competitiveness,” reads the question, posted anonymously over a digital platform and voted up by attendees of the report launch.

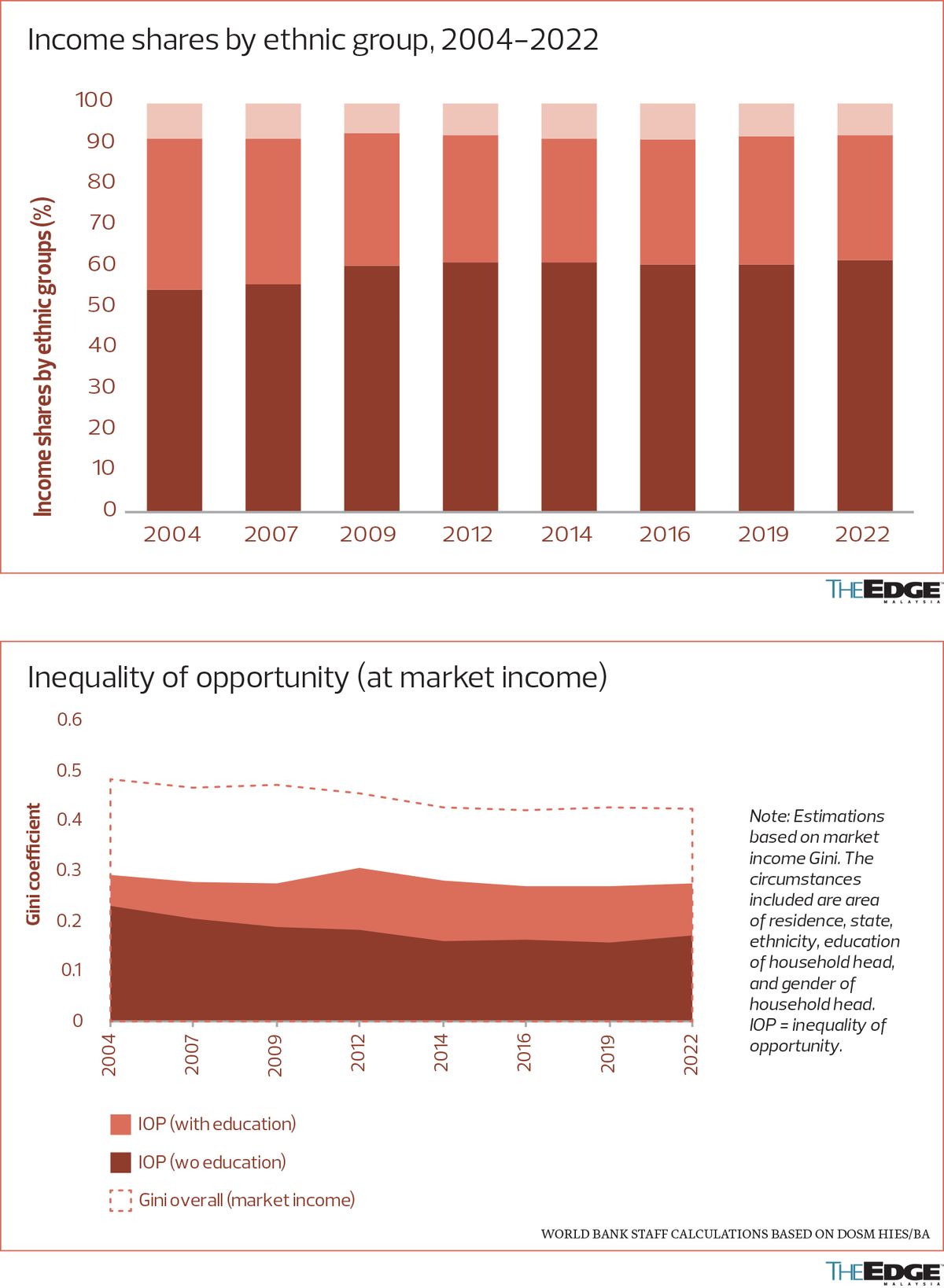

Among other things, the World Bank report said inequality of opportunity — arising from predetermined life circumstances rather than individual effort — accounted for 65% of total market income inequality in 2022, up from 61% in 2004.

Even excluding education, inequality of opportunity still accounts for 40% of total market income inequality, researchers note, without providing a specific breakdown on contributions from each factor (area of residence, state, ethnicity, education and gender of household head) that begin shaping the accumulation of human capital early in life.

In other words, the derivation of the 65% figure for inequality of opportunity remains unclear, although the World Bank stated that its calculations are based on the Department of Statistics of Malaysia (DoSM) Household Income, Expenditure and Basic Amenities (HIES/BA) survey, with estimations derived from market income Gini.

Assuming the researchers are correct about the 65%, it would justify intervention to level the playing field. However, the findings also suggest a need to rethink the approach to such interventions.

Look within, not between, groups first

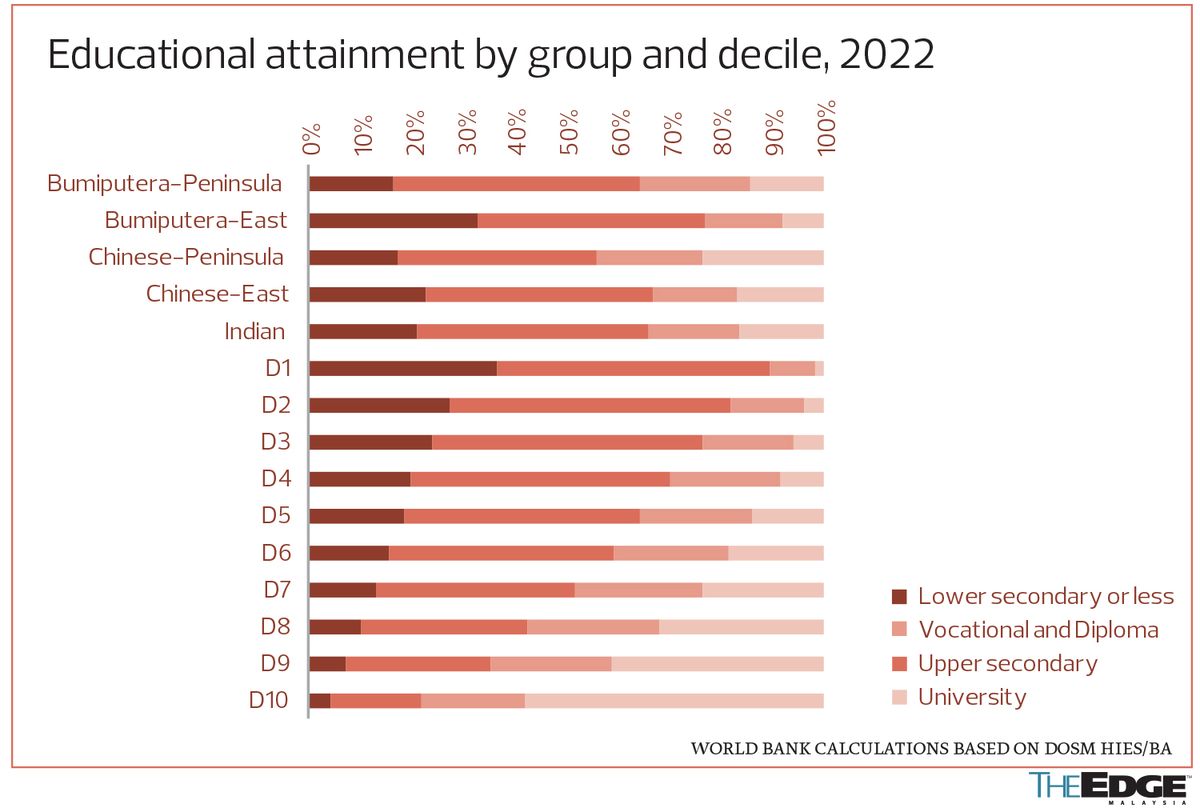

More than two generations after affirmative action was introduced in Malaysia, researchers found “the differences between poor and rich bumiputera are much larger than the differences between the average bumiputera and the average non-bumiputera”, noting that a comparison of the average income between different ethnic groups or between different states “masks differences within groups”, which are far more significant because the “economic differences within ethnic groups and locations are far more important than differences between them”.

In 2022, for instance, “only 13% of total income inequality in Malaysia was explained by differences in average income across ethnicities”, the World Bank researchers say in the report, flagging the fact that 87% of total income inequality reflected differences within each ethnic group.

Similarly, researchers found that 86% of total inequality reflects differences within rather than between states.

Only 20% of total income inequality can be explained by the average income differences between state and ethnic groups combined, the report says, noting that income gains among bumiputera in East Malaysia (Sabah, Sarawak and Labuan) “have been much lower than those of bumiputera on the peninsula”, compounded partly by inequality in access to good-quality health and education services.

Separately, in making policy recommendations, researchers noted that current policies to promote access to public sector employment by bumiputera “miss the fact that these jobs are accessible only to a select few, often better-off bumiputera”.

“Given the limited scope for the public sector to absorb qualified graduates, researchers recommend that policymakers broaden ‘the availability of and access to productive private sector employment by all Malaysians, including less well-off bumiputera and those in East Malaysia’,” recommendations read.

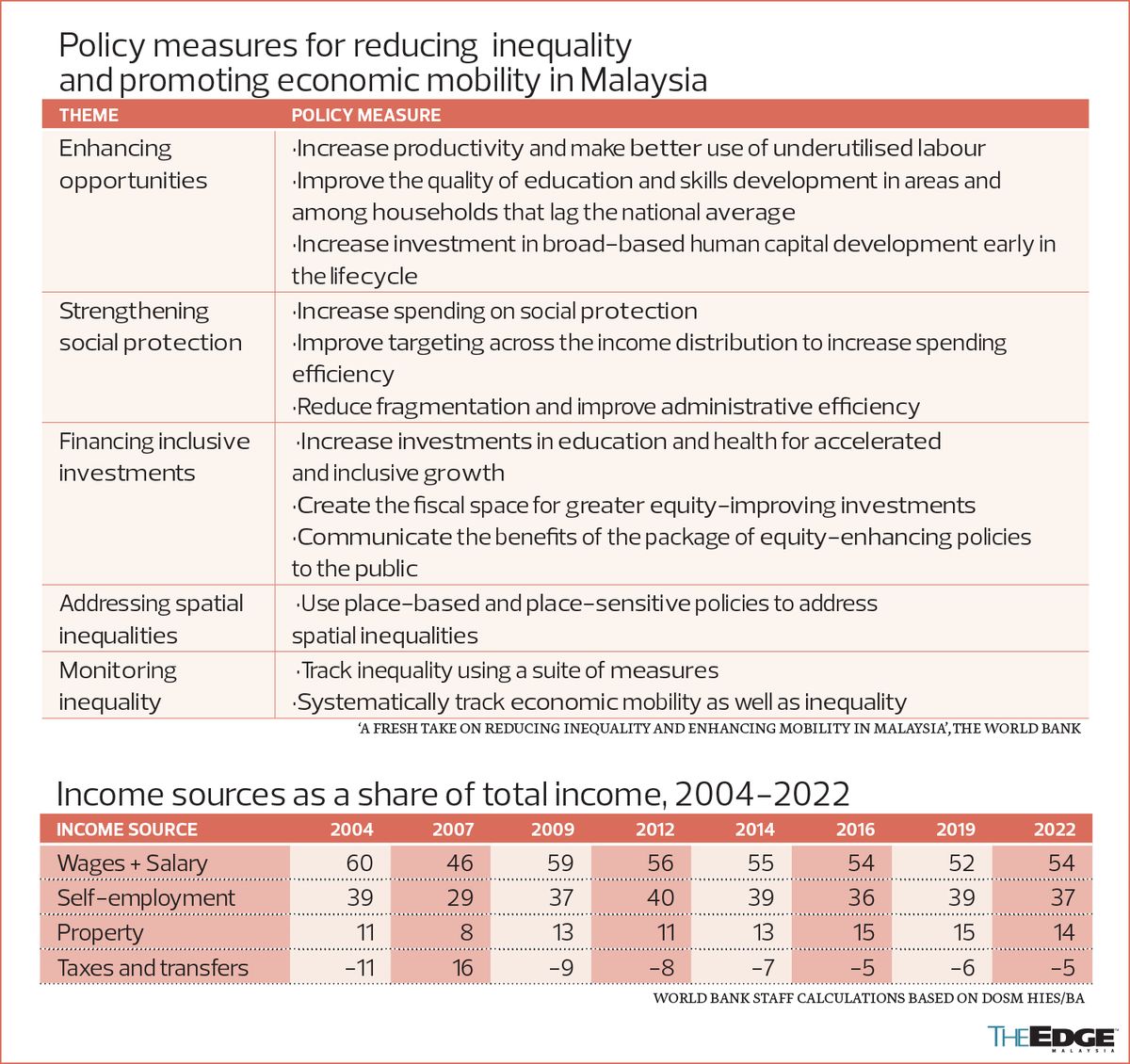

Other policy recommendations in the World Bank report include the need to enhance opportunities to increase productivity and make better use of underutilised labour, noting that many Malaysians have jobs that do not make full use of their education and skills.

It is crucial for the new progressive wage policy to be backed by improvement in productivity, researchers say, also noting the need for improvements in the education system to position the next generation for more productive and remunerative high-skilled employment. To ensure effectiveness, there is a need to track student learning outcomes and teachers’ performance to better understand why some children and young people perform worse than others, both across and within ethnicities and states.

“For Malaysia, improving the quality of education would raise GDP per capita by 0.53 points; universal enrolment at the current quality would do so by only 0.18 points. This points to the importance of rising skills and education quality for both growth and for inequality, since the quality [scores] are lower for poorer children,” researchers say, noting that Malaysia’s journey towards high-income status needs GDP per capita to grow at 5% annually, which in turn requires roughly twice the growth in worker productivity compared to the achievements of the past three decades.

Wealth inequality, rent-thick activities

Even as the people’s perception of a widening gap between the rich and poor grows amid the stalling of inequality reduction (statistics-wise), the World Bank researchers said inequality “would be even higher if the incomes of the richest Malaysians were accounted for” in the household income and expenditure surveys done by DoSM, which cover mostly income from wages but likely could not fully capture wealth from financial assets, investments and savings over time that are “highly concentrated” among the wealthy few. Moreover, taxes on wages or labour are often higher than taxes on capital income that are more easily evaded.

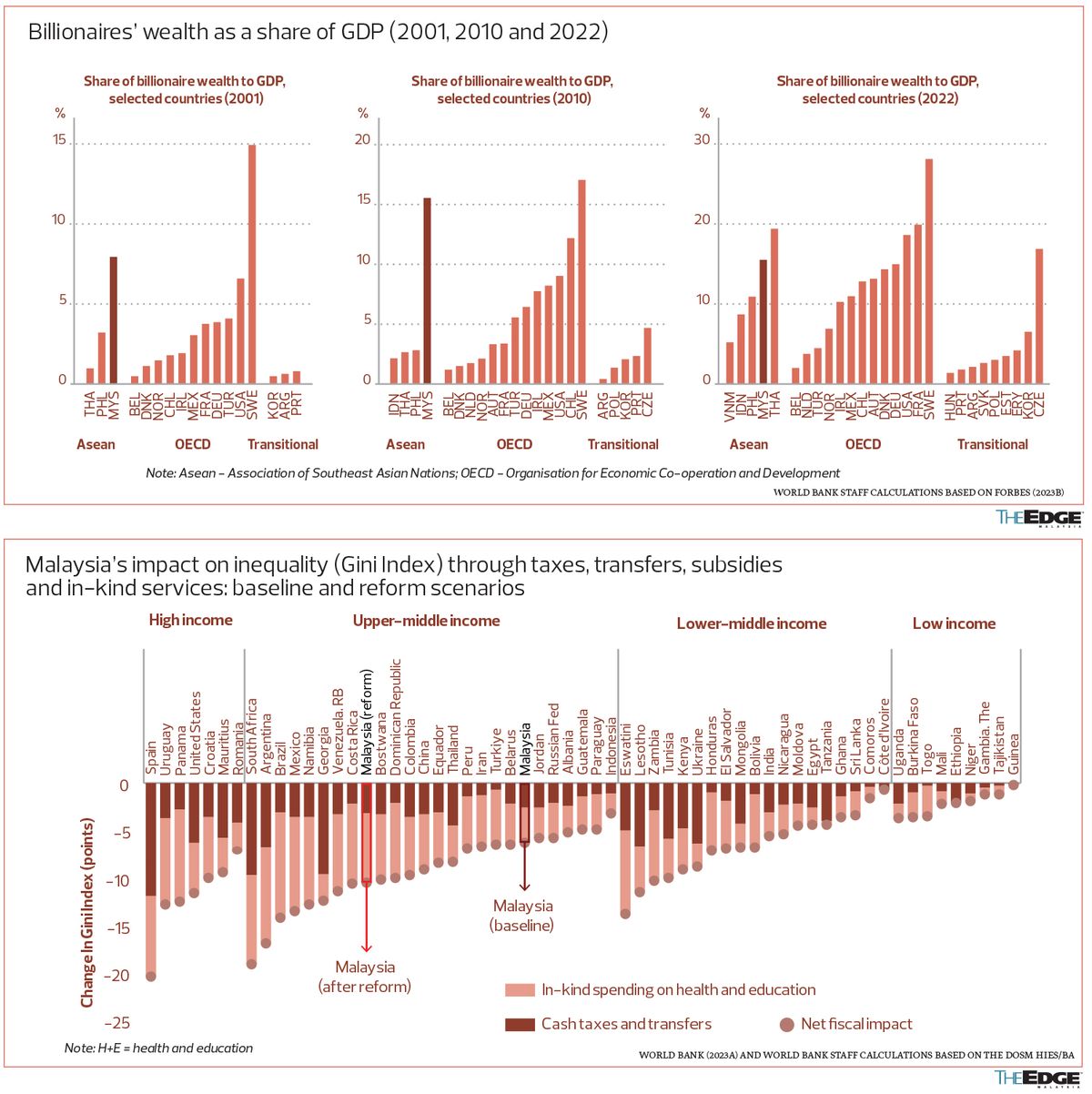

The World Bank report provides less insight into wealth inequality, which may well be more entrenched than income inequality, but does provide some observations, citing third-party data.

“While data are scarce (and existing data have limitations), the available evidence indicates that wealth inequality is even more highly concentrated than incomes in Malaysia, as in other Southeast Asian countries. The richest 10% of Malaysian households held 70% of wealth (in 2014), meaning that this outsized income share benefits the richer few,” the World Bank researchers say, citing data from Credit Suisse.

“Further, data from Forbes magazine shows that the aggregate net worth of Malaysia’s billionaires as a share of GDP has steadily increased in the past two decades, reaching 13% of GDP in 2023, and is high relative to that in Asean, OECD and transitional countries.

“And wealth is concentrated in sectors considered ‘rent-thick’,” the researchers note, describing ‘rent-thick’ economic activity and sectors as those in which “there is a pervasive role of the state in providing licences, a reputation of illegality or potential monopolistic practices”. In contrast, non-rent-thick sectors have more limited interaction with the state, the regulator has a good reputation and there is little anecdotal evidence of illegal practices.

“Of Malaysia’s 50 richest individuals in 2024, 28 made their wealth from sectors considered rent-thick (real estate, construction, infrastructure or ports sector, media, cement and mining). Similarly, wealth from rent-thick sectors accounts for 72% of the aggregate net wealth of these individuals,” the World Bank report says.

New ways, new outcomes

Researchers consider that Malaysia’s system of taxes and transfers — which can help mitigate shocks and support vulnerable and targeted households through the income-generating process — is progressive and reduces inequality, but it trails many upper-middle-income country (UMIC) peers and even some lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) in the inequality reduction that it achieves.

“Taxes, cash transfers and subsidies in Malaysia reduce inequality by 2.4 points from the pre-fiscal level, which is close to the UMIC average. When non-cash health and education benefits are included, Malaysia’s inequality reduction is 4.1 points higher, for a total of 6.5 points. While the fiscal system achieves some inequality reduction and is progressive, it trails many UMIC peers. It ranks 18th out of 25 UMICs with 10 LMICs performing better than Malaysia,” the researchers note.

They concur that phased fiscal reforms could generate new revenues, allow increased development spending, and reduce poverty and inequality. “The first phase would be to remove fuel subsidies and compensate poorer households with increased social assistance.

“Phase 2 would significantly increase long-term revenues through both indirect and direct taxation. Malaysia’s indirect tax collection, at 3% of GDP, is particularly low, below even the low-income countries’ (LIC) average. Thus, in the short term at least, increased revenue collection can be achieved through indirect taxation,” researchers say, again recommending the reintroduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) or Value-Added Tax (VAT), “since it is widely regarded as one of the most efficient taxes in a country’s toolkit and can be implemented widely and swiftly”.

“A simulation exercise shows that replacing the current sales and services tax (SST) with a GST that has a 10% base rate with few exemptions or preferential rates would generate additional revenues constituting about 1% of GDP, with relatively little impact on inequality. Moreover, the estimated impact of consumption taxes may be even more progressive because poor households have a higher degree of informal consumption, which attracts less tax.” The report notes that the burden on poorer households can be alleviated by better-targeted transfers and the introduction of a targeted GST rebate.

“Better targeting of social assistance towards the poorest households in the bottom 40%, along with a tax rebate, would offset the impact of a GST increase on poverty, have no impact on inequality and still leave additional fiscal savings equivalent to 2% of GDP.”

Stressing the need to fit today’s needs, researchers say emphasis on access gap closure in Malaysia’s major planning and strategy documents, including the 12th Malaysia Plan and Madani Economy framework, “may have contributed to inequality reduction in the past, but it may not be sufficient to address the gaps that remain today”.

“Past policies may have helped narrow access gaps, especially in terms of increased tertiary educational attainment, but that may not be sufficient or appropriate going forward for Malaysia as a high-income and developed economy,” the World Bank reiterates.

“Further research is needed to understand why there is an income disparity between some bumiputera workers and others who have similar education and other attributes. Any complementary policies that do focus on the reasons for any further ethnic gaps need to ensure they benefit the disadvantaged bumiputera rather than those who are already succeeding. Because inequality of outcomes has roots early in life, addressing inequality for future generations must emphasise increasing these opportunities for all Malaysians.”

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.