(Photo by Suhaimi Yusuf/The Edge)

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 30, 2024 - January 12, 2025

All kinds of targets have been made by countries and companies to cut emissions, protect forests or increase renewable energy penetration.

But there is also scrutiny on these targets and whether it is greenwashing. In this section, ESG explores this topic from three different angles.

Making commitments that count

Malaysia has set two climate targets. However, there is little available information on how the country will achieve these goals.

One of these is the nationally determined contribution (NDC), which is required of all signatories to the Paris Agreement. Malaysia’s NDC is to reduce its economy-wide carbon intensity, measured against its GDP (2005 baseline), by 45% by 2030. An updated target, however, has to be submitted by February 2025.

The other climate target was confirmed this year, which is to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

The Long-term Low Emissions Development Strategy (LT-LEDS), which the government has said is being prepared for several years now, should have more information on what the country has to do to achieve these targets.

But where is Malaysia now? The best official source of information is from the Fourth National Communications report that Malaysia submitted to the United Nations (UN) earlier this year and the fourth biennial update report (BUR4) in 2022.

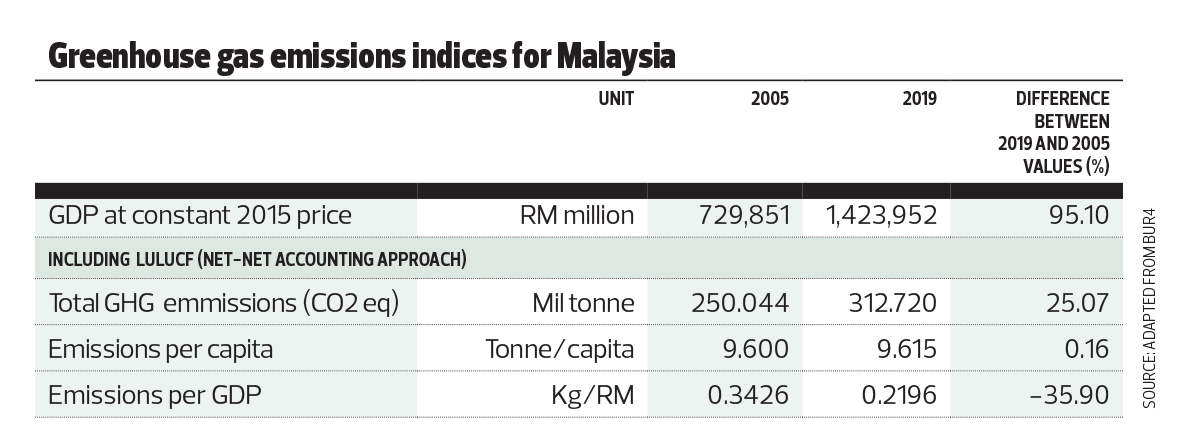

In a table nestled in the more than 300 pages of the BUR4 (refer to table), it shows that emissions per GDP fell 35.9% in 2019, which is the latest data available.

More information can be expected from the Biennial Transparency Report, which should be submitted by Malaysia to the UN at the end of this month, says Ahmad Afandi, fellow at the Institute of Strategic & International Studies Malaysia.

But since Malaysia’s NDC is an intensity target, it is likely to be met. Pieter E Stek, senior lecturer at the Asia School of Business, cites data from the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) showing that globally, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have been rising at a slower rate than GDP growth.

GHG emissions have increased over the past decade, reaching a record high of 53 GtCO2eq in 2023. However, GHG emissions per unit of GDP PPP (purchasing power parity) fell in general from 1990 to 2023, according to EDGAR.

A concern for Malaysia is the recent surge of investments in power-hungry activities like data centres, which might spike energy consumption, Ahmad Afandi observes.

Harder to tell for the net zero target

Malaysia’s ambition to reach net zero emissions by 2050 is the same as countries like the UK, the US and Singapore, and relatively early compared with neighbouring countries. Is Malaysia being too ambitious or relying too much on its forest as a carbon sink to offset the increase in emissions?

Malaysia was accused of over-claiming the ability of its forests to absorb carbon in a Washington Post report three years ago. In response, the Malaysian government defended its data and processes, which were according to the UN’s guidelines.

Regardless, Ahmad Afandi says it must be noted that developed countries like the US and the UK, which are responsible for historical emissions, should be more ambitious.

But it is unclear how Malaysia aims to achieve the net zero target. The only mention of how current policies will support the target is from the National Energy Transition Roadmap (NETR), which projects that the actions will deliver a 32% reduction in GHG emissions in the energy sector by 2050 (2019 baseline).

This is assuming that the total primary energy source will become majority natural gas (56%), with renewable energy (RE) contributing 23% by then. The NETR’s 50 initiatives cover hydrogen, green mobility and carbon capture, utilisation and storage, among other things.

More clarity is needed on how these can be achieved, and how the NETR can support the net zero target. Minister of Economy Rafizi Ramli recently said Malaysia should consider nuclear power as well, but this was not mentioned in the NETR.

“My colleague and I have expressed concern about plans to increase power generation from natural gas in the NETR, not least because the government has said there are insufficient domestic natural gas reserves to meet projected demand. Increasing the use of natural gas poses risks for Malaysia’s energy security, and is likely more expensive than RE alternatives, especially given the continually falling cost of solar panels,” says Stek.

The intermittency of sources like solar will have to be tackled with battery technology, which are not yet economically feasible. If more Large Scale Solar projects were to be built, land requirements would be an issue, Ahmad Afandi observes.

“Malaysia may need to rely on sources from a cross-border energy system, such as the Asean power grid. But ironically, we intend to sell our RE to other countries,” he says.

The energy needs of data centres, which are power hungry, will need to be considered as well, since the NETR was launched before these investments poured in this year.

Additionally, Malaysia will introduce a carbon tax by 2026 on the iron, steel and energy sectors. But it is unclear how this will contribute to the net zero target.

As for carbon sinks, if Malaysia were to bank on forests to absorb the increase in GHG emissions, climate targets must be aligned with forestry and biodiversity targets.

“For instance, a certain percentage of forests need to be kept in certain areas to conserve a targeted million tonnes of GHG by 2050. We should go into more granular details and specify habitat types to conserve,” says Ahmad Afandi.

This can be difficult to do because forests are a state matter, but he believes it can be more acceptable if there are “fair share contributions” from each state to achieve national targets pertinent to forest conservation, depending on state circumstances.

There must also be consideration on how many carbon credits generated from Malaysian forests that can be claimed by entities outside of the country, lest it threatens Malaysia’s climate targets.

“There is understandably a lot of attention on the energy sector but it’s impossible for Malaysia to achieve net zero and its NDC without conserving its forest and biodiversity, since more than 65% of our annual emissions is offset by forests,” says Ahmad Afandi.

“Even the NETR made a strong assumption that our forests will stand as it is up to 2050 to meet its net zero aspirations. The government recognises this through various statements from the ministry, but it has not been matched with equal actions.”

The ecological fiscal transfer is not enough, he opines, so more innovative financing schemes beyond the carbon market, biodiversity credits and compensation are needed.

Specific pathways and strong policy instruments needed

The long-awaited LT-LEDS should have information highlighting the emissions-reduction pathways for the country based on various scenario planning projections, with sector-specific targets and policy measures, among other things.

Ahmad Afandi believes that is needed, as current policy measures and plans, such as the NETR, are sectoral and not explicitly linked to a quantified emissions reduction target.

“For instance, there are no emissions policy targets associated with the transport sector, although there is a target on public transport modal share and share of electric vehicles. For forestry, although there is a 50% forest cover pledge, there is no GHG target associated with this, such as how much carbon stock Malaysia has to conserve to be net zero or meet its NDC,” says Ahmad Afandi.

Stronger policy instruments, whether regulatory or market-based, are needed, as is financing, to achieve these strategies. The policies must be harmonised as well. For instance, the goal to increase the use of public transport cannot clash with another national target to increase private vehicle ownership.

These actions should not be framed as a challenge but also as an opportunity, says Stek. For instance, adopting RE is an opportunity to create a less-polluting energy system, the circular economy can increase the lifetime value of products and reducing car use and emissions increases the walkability and liveability of cities.

“Governments should also avoid a kind of ‘climate austerity’ where ordinary people feel they are sacrificing, while the elite continue to drive, jet set and overconsume. A good climate policy is one that delivers tangible benefits in addition to helping reduce climate change. In that sense, Malaysia should adopt a climate bill, but it should be part of a broader technical- and socio-economic transformation agenda,” he says.

It must be noted that there is more global scrutiny on net zero targets now, with entities like the ISO and the Taskforce on Net Zero Policy working on guidelines for credible net zero targets.

According to the Net Zero Stocktake 2024 report, although net zero target-setting has increased, 5% of less of entities across companies, states and regions, and cities meet the minimum procedural and substantive integrity criteria.

“The elements most lacking are clarity on the use of offsets, coverage of all emission scopes, and specifying what greenhouse gases are in scope. You could add clarity on the intended use of fossil fuels to that list,” says John Lang, project lead at Net Zero Tracker, which prepared the report.

Malaysia’s net zero target is not enshrined in law at the moment. In the Net Zero Tracker website, it is noted that Malaysia’s net zero plan is incomplete, with unspecified formal accountability mechanisms and plans to use external offset credits.

Lang suggests Malaysia could commit to further phase out oil and gas exploration and enshrine the net zero target in legislation.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- China amplifies rebuke of Li Ka-shing’s Panama Port deal with BlackRock

- Batik Air throws support behind Subang Airport's expansion, urges faster slot allocation following AirAsia’s departure

- Forest City expands transportation infrastructure to support SFZ and JS-SEZ

- Gold counters on Bursa Malaysia surge as safe haven demand rises amid concerns over US economy

- Donald Trump makes Chinese stocks great again

- FBM KLCI up 0.14% to 1,512.15 on March 14, 2025

- Putin, Saudi Crown Prince discuss Opec+ agreements and Ukraine crisis in call

- Pertama Digital acquires 80% stakes in two companies for RM106m as part of its regularisation plan

- BNM names Aznan Abdul Aziz as deputy governor as Jessica Chew retires

- China, Russia back Iran as Trump presses Tehran for nuclear talks

Level 3, Menara KLK, 1 Jalan PJU 7/6, Mutiara Damansara, 47810 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

Copyright © 1999-2025 The Edge Communications Sdn. Bhd. 199301012242 (266980-X). All rights reserved