(Photo by Mohd Izwan Mohd Nazam/The Edge)

This article first appeared in Forum, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 31, 2025 - April 6, 2025

Malaysia has long trumpeted its trade prowess, with total trade numbers going beyond RM1 trillion in several years. Magnificent achievement, no doubt. Yet, with such stellar numbers, the man on the street is often wondering how that translates into what goes into their wallet.

The background for this is simple: Malaysia, where manufacturing is concerned, is primarily an intermediate goods producer. Unlike most other economies, Malaysia doesn’t have many of its own final products and branded items. My heart would sing for joy if Malaysia were an exporter of electric vehicles or supercomputers or tool and die machinery, or a maker of ships and aircraft, all wholly owned by Malaysians. Instead, we have grown too dependent on foreign direct investment, and the story there is well known.

How does this relate to exports, imports, gross domestic product (GDP) and the man in the street’s wallet?

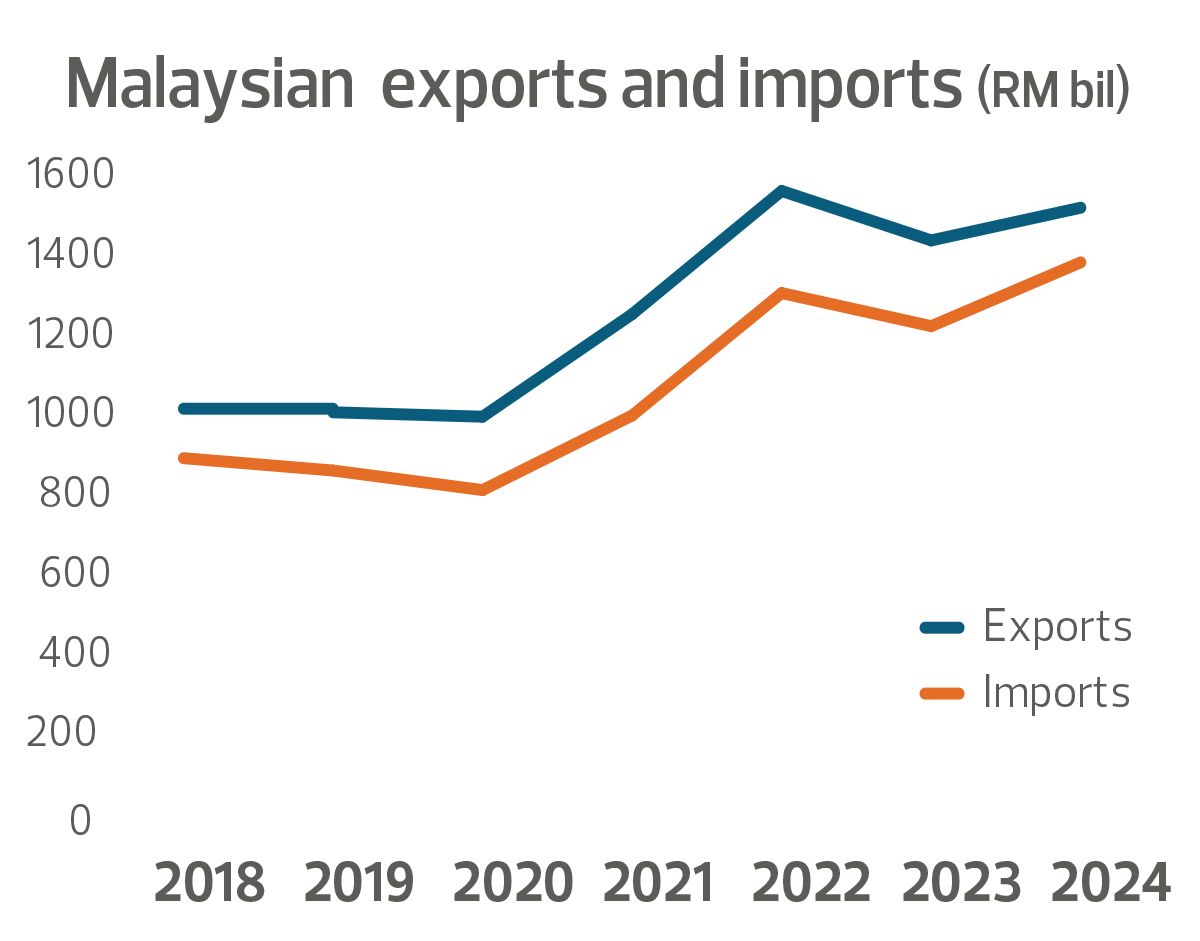

Malaysia’s exports are quite stellar, reaching RM1.5 trillion in 2024 (all numbers are from the Department of Statistics Malaysia), for the fourth year in a row. Imports kept pace, at 2024’s RM1.3 trillion for the third year in a row.

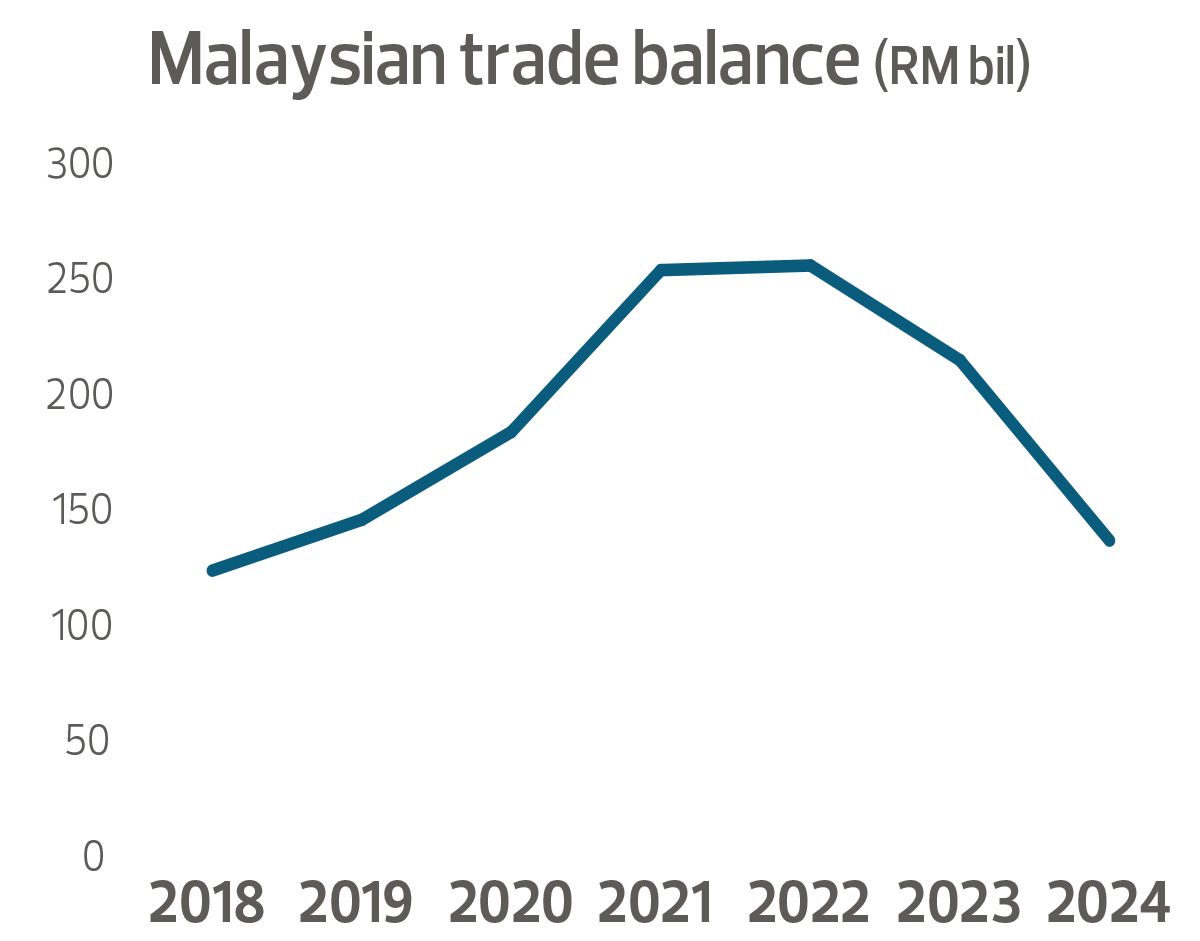

The trade balance remains positive, at RM137 billion.

The chart below shows the export and import numbers from 2018:

The trade balance is as follows:

Immediately it is obvious that the trade balance, a number that is not properly emphasised in announcements, has peaked and is falling despite exports and imports rising.

This is also reflected in the trade balance as a percentage of total trade as per below:

What is puzzling is why the trade balance keeps falling as total trade rises. This certainly fits into the economic theorem of diminishing returns; that is, the more you try to sell, the lower the returns you get out of it. Think of it as a food stall seller; the more fried koay teow he wants to sell, the cheaper he has to offer it. His costs (imports herein) remain the same as he prepares more for sale, but what goes down are his margins (trade balance). This, of course, is a very simplistic view representing an economic system as there are substantial categories in imports, for example, pure consumption goods, that are being overlooked in this case.

How does this fit into what should enter a citizen’s wallet?

Remember the basic GDP equation? GDP = consumption (C) + investment (I) + government spending (G) + net exports (X–M), where X = exports and M = imports.

Clearly from the above, what matters to an economy is the “profit margin” of trade, or the trade balance (X–M). As it increases, GDP increases and, hence, has a good chance of improving the layman’s quality of life via his wallet, among others (through smart policy choices, needless to say). If the trade balance is zero irrespective of exports or total trade being huge, like 50 times that of GDP, then there is no impact upon GDP.

Now, to reiterate, Malaysia is primarily an intermediate goods exporter, and that has its drawbacks, already well known. Far better that the country segues itself into a final goods producer and exporter so as to grab the income that comes from an entire value chain, rather than just profiting from a small part of the chain. Hence, aiming for Malaysian-manufactured goods’ final products and brands is the way to go. It can be protected in its infancy — until it can compete regionally — via tariffs.

Indeed, in the light of ongoing world affairs, it must be pointed out that such tariffs must be applied evenly to the world and not targeted against some countries (or three, like US President Donald Trump has done). What America has done is quite rightly attack three countries. It’s a war via trade. It’s hard to see how local US companies would benefit under such an umbrella.

Thus, before a positive trade balance becomes a trade deficit, a situation Malaysia just cannot afford, reindustrialisation of the country is a must policy move to make.

Huzaime Hamid is the chairman and CEO of Ingenium Advisors, Malaysia’s financial macroeconomics advisory, and the author of two economics books, with another being worked on

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Indonesia detains judge for alleged bribery in palm oil case involving Wilmar's unit

- Former Seberang Jaya assemblyman Dr Radin Muhamad Amin passes away

- Trump says he will provide more info on chips tariffs on Monday

- Malaysia to champion smallholder inclusion, sustainable trade at inaugural FACT 2025 Forum — plantation minister

- Japan doesn’t plan to use US Treasuries as tariff talk leverage