More Malaysians will turn to public hospitals if they are priced out by exorbitant insurance premiums. (Photo by Low Yen Yeing/The Edge)

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 31, 2025 - April 6, 2025

THE ultra-rich do not need medical insurance. The well-heeled can afford all the healthcare, wellness and aesthetic packages they want. Then, who are the people who have signed up for medical insurance that allows coverage of a whopping RM8 million (US$1.8 million) a year and without a lifetime claim limit?

“Medical and health insurance or takaful (MHIT) products with high utilisation limits of up to RM8 million annually, and without lifetime claim limits, are generally associated with higher healthcare utilisation,” Bank Negara Malaysia wrote in the feature article, “Securing Sustainable Access to Medical and Health Insurance or Takaful Protection” in its 2024 annual report released on March 24.

Is Bank Negara blaming consumers, insurers or both when it says “the design of MHIT products also plays a role in this issue” while discussing runaway medical inflation in Malaysia?

Are consumers to blame for buying an insurance package that allows them to claim for probably any type of medical treatment — necessary or “just in case” — that their MHIT product provides cover for since they probably need to pay next to nothing out of pocket to the hospital? After all, that peace of mind that comes from not having to worry about the hospital bill is what the MHIT premium is for, right?

Private healthcare providers would, of course, roll out the red carpet for MHIT holders, especially those with such high claim limits.

Did the insurers complain when taking commissions and fees for selling those MHIT products with high claim limits, only to say now that MHIT premiums needed to go up due to high medical inflation post-Covid-19?

Was there oversight on the part of Bank Negara, which regulates insurers, for allowing such MHIT products to be sold? Were insurers caught unawares by this runaway spiralling healthcare charges-claims cycle that had snowballed beyond the expectations of the actuarial experts who priced the MHIT products for their employers’ benefit?

Were MHIT products adequately checked for any under-pricing for market share gains? (See accompanying story for Bank Negara’s replies to questions from The Edge.)

Solutions, reforms for sustainability

Whether it is the fault of one or two parties or there is blame to be shared, the chickens have come home to roost and it is likely that consumers and taxpayers will need to pay the price should more people have no choice but to turn to public hospitals if they can no longer afford private healthcare or their medical insurance premiums.

This will weigh on public finances as well as already strained government-funded healthcare facilities, causing consternation at the Ministry of Finance. It is little wonder that the Ministry of Health (MoH) is working alongside Bank Negara and the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) to expedite the necessary healthcare reforms and put in place longer-term solutions to address the high private healthcare charges and rein in medical inflation. This only covers part of the populace, given that about half of the labour force are EPF members. Membership is on a voluntary basis for those who are not salaried.

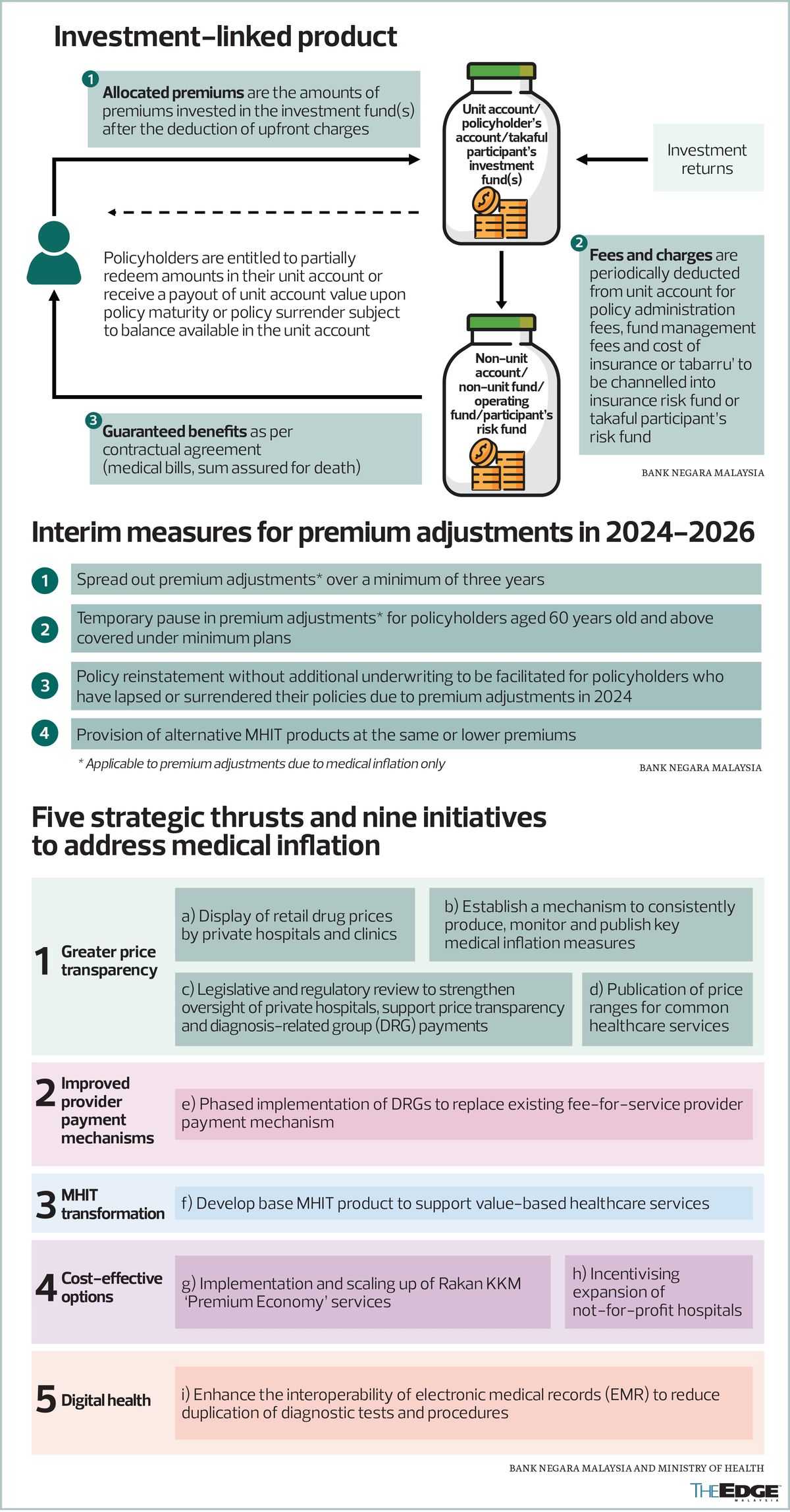

This is on top of other measures such as a phased implementation of a diagnosis-related group (DRG) system to replace the existing fee-for-service payment mechanism, as well as greater price transparency by disclosing the price range of common healthcare services and displaying the retail prices of medicines sold by private hospitals and clinics. Implementation will likely require legislative and regulatory review to strengthen the government’s oversight on private hospitals and to support price transparency and DRG implementation (see “Five strategic thrusts and nine initiatives to address medical inflation”).

It is understood that the details are being worked out, by year end, for a basic MHIT product that will ensure more equitable access to medical treatment that can be paid for with EPF savings in either Account 2 or Account 3. It is not immediately certain if this is meant to be expanded into a national basic insurance plan, given that all Malaysians aged 14 and above can sign up to be an EPF member.

It is understood that this solution should provide a more sustainable alternative MHIT product to consumers and is different from the existing i-Lindung facility, for which more than 153,618 EPF members had withdrawn RM51 million between July 2022 and December 2024 to pay for life insurance and critical illness coverage.

When proposing nine measures to address the escalating healthcare costs, Malaysia’s insurance and takaful players called for greater transparency in the pricing of healthcare services and said they intend to collaborate with Bank Negara in developing a basic, long-term, sustainable insurance and takaful product that allows top-ups by those seeking additional coverage.

Back to that very high MHIT package Bank Negara mentioned. For perspective, the RM8 million a year claim limit works out to around RM22,000 a day or RM666,666 a month. Bank Negara did not mention the monthly premium, but it is likely that the monthly insurance premium is a mere fraction of that very high claim limit. Even an annual limit of RM1 million would work out to RM83,333 a month, if there is no lifetime cap on claims.

It would be interesting to know the changes to the premiums as well as the annual insurance charges for that MHIT package with the RM8 million a year claims limit, given the upward repricing of the MHIT product premium on the back of high healthcare costs from last year. As the coverage is high, it is probably an investment-linked MHIT product.

Investment-linked MHIT products constitute about 70% of the total individual MHIT business, as measured by the number of covered or insured persons in 2023, according to Bank Negara.

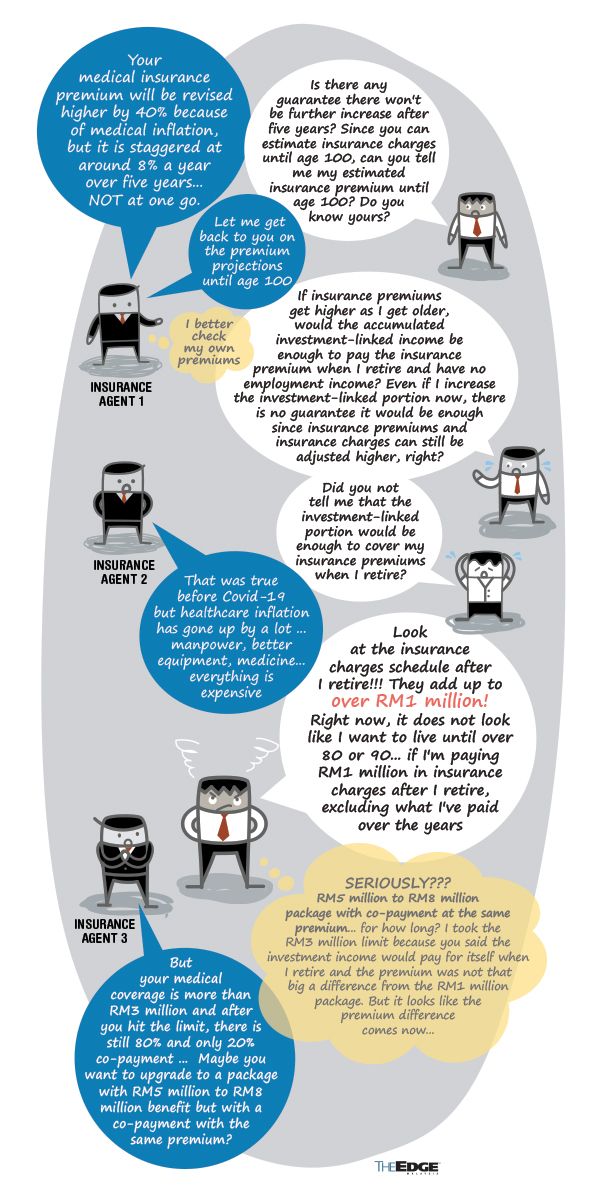

Check future premiums, insurance charges

Most consumers are familiar with insurance premiums, which is what they pay the insurer monthly, quarterly or annually for medical coverage and upfront charges for insurance expenses. Premiums also cover the purchase of units in investment-linked funds for investment-linked MHIT products.

Insurance charges, meanwhile, are a sum deducted by insurers from the value of your investment-linked funds account. The layman may think of this account that holds the cumulative value of investment units as the “cash value” of your insurance policy.

At the risk of oversimplification, if you have been told that your insurance premium will “pay for itself” when you retire, the monthly premium will probably come out of this “reserves” account where the balances should have grown over the years, assuming that the investment returns are positive and greater than the insurance charges. If you started young, they should, given that insurance charges generally increase as you get older — even more so after the retirement age of 60.

Given the spike in medical inflation, especially post-pandemic, consumers with investment-linked products should check to see if the investment returns on the premiums they pay can realistically grow reserves big enough to cover the insurance charges that will generally be higher when one is older. This is to avoid discovering severe shortfalls when they are retired or old and are more likely to need medical insurance coverage.

Consumers who have carefully read the schedules appended in the letters informing them of their MHIT premium increase in the next three to five years would have noticed a schedule of annual insurance charges from their current age until they are 100. Consumers, especially those with high MHIT coverage, would probably have noticed a huge spike in insurance charges after the age of 60, 70, 80 and 90.

These insurance charges are not the same as one’s future insurance premium.

Many might not have noticed the schedule of insurance charges at all, given that the letter is to tell them how much their MHIT premium will go up in 2025, 2026 and 2027, if not for the next five years.

Those taking multimillion-ringgit MHIT packages might not even flinch at the staggered hike in MHIT premiums over the next five years, thanks to interim measures introduced by Bank Negara in December 2024.

At least 80% of policyholders are expected to see less than a 10% increase in their premium a year, according to Bank Negara. (Scan or click the QR code to read “Cover Story: Who pays the price of runaway healthcare inflation?” published on Dec 23, 2024).

But there is really no assurance that premiums for MHIT packages will not be revised higher again after three or five years, is there? How sure are you if you will be able to afford your insurance premium, not just at this time, but five or 10 years from now — especially in post-retirement when insurance charges are likely to be higher?

“If I’m not sure if I can afford future insurance premiums, will I be better off saving for my medical bills instead of paying for an insurance medical card?” one observer asks, noting that private hospital bills for self-paying patients are almost certain to be lower than those with MHIT coverage.

The risk of more people who thought they had adequate insurance coverage, but may not actually in their old age — when they are more likely to need medical treatment and MHIT premiums are likely to be more expensive — is real as insurance premiums generally increase with age.

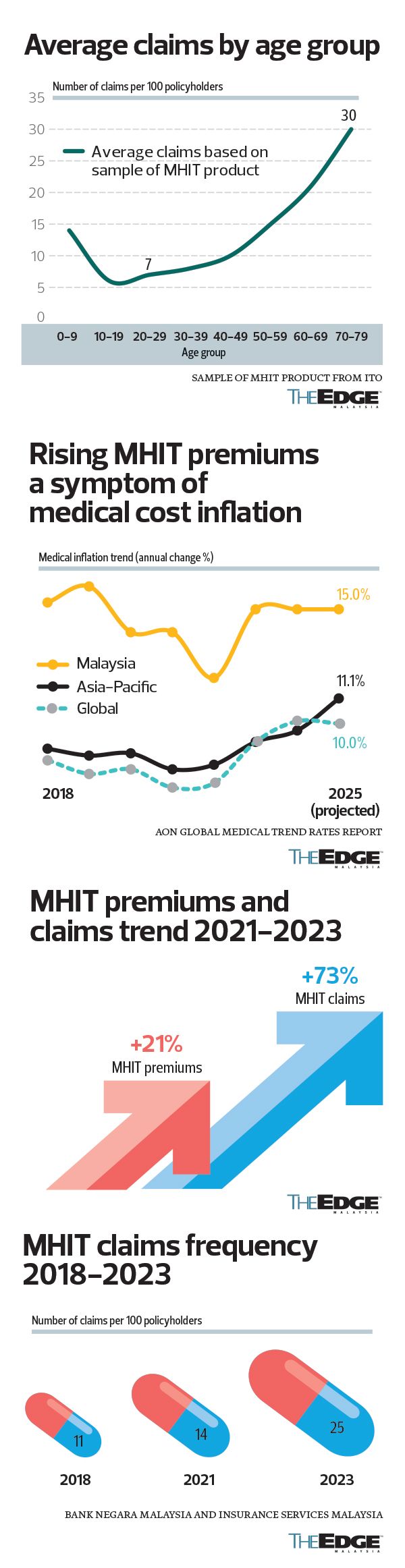

Data from a sampled product show that there are 30 claims for every 100 policyholders aged 70 to 79 — significantly higher than the seven claims per every 100 for policyholders aged 20 to 29, says Bank Negara (see chart on average claims by age group).

As at 2023, there were 7.7 million individuals covered under MHIT products, says Bank Negara.

How many can continue to afford an annual increase in premiums even if the increases are capped at 10% a year?

Bank Negara’s interim measures in place from end-2024 until end-2026 — capping near-term insurance premium hikes by staggering them over at least three years, and stopping MHIT premium increases for policyholders aged 60 and above for a year from their policy anniversary, and mandating the reinstatement of MHIT policies surrendered or lapsed in 2024 due to the repricing without additional underwriting — provided temporary respite to MHIT holders, buying time for the implementation of critical broader health reforms to contain medical inflation.

“The interim measures cannot be sustained if high medical inflation persists,” Bank Negara said in that same article in its 2024 annual report. “In 2024, some of the premium adjustments were quite significant. While 61% of affected policies experienced less than 20% premium increase, about 9% of affected policies experienced more than 40% premium increase.”

At least three holders of investment-linked MHIT products with a claims limit of more than RM1 million, who had been notified of the more than 30% hike in insurance premiums over the next three to five years, told The Edge that if one were to add up the annual insurance charges from age 55 to 100, the amount would “easily be more than RM500,000” and even close to RM1 million. And they are not holders of that MHIT package with a claims limit of RM8 million mentioned by Bank Negara. They have asked for a projection of insurance premiums beyond five years but have yet to receive details at press time.

New guidelines by Bank Negara on MHIT product disclosure sheets require insurance and takaful operators to provide a projection of premiums to show clients if they can afford the premium increases over time.

In Singapore, where healthcare and retirement reforms have incorporated healthcare insurance premiums under the Central Provident Fund (CPF) with the creation of a national basic health insurance plan called MediShield Life, an online tool has just been launched to allow Singaporeans to compare key features and cost of their long-term MediSave savings and project up to 30 years of healthcare insurance premiums for their chosen Integrated Shield Plans (IPs) and preferred hospital ward type.

Overall, Malaysia spent RM84.2 billion on healthcare in 2023, including total expenditure paid by MoH, out-of-pocket expenditure by households, MHIT, other ministries, agencies and local authorities, private corporations and non-profit institutions. The expenses included cost of curative, rehabilitative, and long-term nursing care, health promotion and prevention, medical goods and health programme administration. MoH’s budget allocation was RM36.85 billion in 2023, RM41.22 billion in 2024 and RM45.27 billion in 2025.

According to Bank Negara, the amount of healthcare spending funded by MHIT has grown six times over the past two decades, from RM0.96 billion in 2003 to RM6.75 billion in 2023.

Between 2021 and 2023, the total cost of MHIT claims increased by 73%, far surpassing the 21% growth in MHIT premiums collected. Apart from higher average cost of treatments, Bank Negara says this was also driven by more frequent utilisation of medical services, as seen by the increase in claims frequency. In 2018, 11 claims were made for every 100 policyholders. But by 2023, this number had more than doubled to 25 claims. This is further compounded by the high cost of hospital supplies and services, such as pharmaceuticals, laboratory fees and consumables (such as gloves), which are currently unregulated and constitute 59% to 70% of overall private hospital bills, depending on the type of treatment and can have a significant impact on the overall claims cost.

A private healthcare expert tells The Edge that the seemingly high charges for gloves and the like are a way for private hospitals to, for the lack of a better word, “creatively bill” the medical expenses in a way that allows the patient to maximise the claimable amount from insurance.

“Otherwise, the patient may not be able to afford the room they stayed in on just RM200 or RM300 board a day. Our hospital beds are well equipped with medical equipment and specialised care on call. Does it make sense for VIP room fees per day to be cheaper than a hotel?” says the healthcare practitioner, noting that hospitals in certain countries can file the difference under miscellaneous “hospital fees” so the price of gloves can be more reflective of actual prices.

Whether it is for the convenience of their patient with MHIT coverage or the bottom line, it is clear that Malaysia’s medical inflation, projected at 15% in 2025, is higher than the global and Asia-Pacific averages of 10% and 11% respectively. The longer holders of MHIT products take to make sure they can afford their premiums, the shorter the time frame they may have to switch to a more sustainable product. Without broader healthcare reforms, more consumers may find themselves priced out. Let this be a wake-up call, not just for consumers and policymakers, but for all.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Trump says he is reluctant to keep raising tariffs on China

- US stock rebound fizzles as Trump goes on offensive

- Court orders preacher to pay RM2.5m to KJ for defamatory statements on Covid vaccines

- Chinese tea chain’s US shares rise 43% as IPO defies volatility

- CIMB Securities widens WCT's discount as order book challenges mount, keeps 'hold' call

- US will abandon Ukraine peace efforts if no progress made soon, Rubio says

- China dismisses Zelenskiy's claim it is supplying weapons to Russia

- Apple CEO spoke with Lutnick about tariff impact on iPhone prices — Washington Post

- Indonesia weighs costly US arms purchases to curb tariff threat

- Trump says he is 100% confident on Europe trade deal, 'everybody' on his priority list