Lending to non-depository financial institutions offers the prospect of additional revenue for banks, many of whom have been squeezed amid heightened competition for deposits.

(March 27): One of American banks’ fastest-growing businesses is lending to the very companies trying to grab their market share.

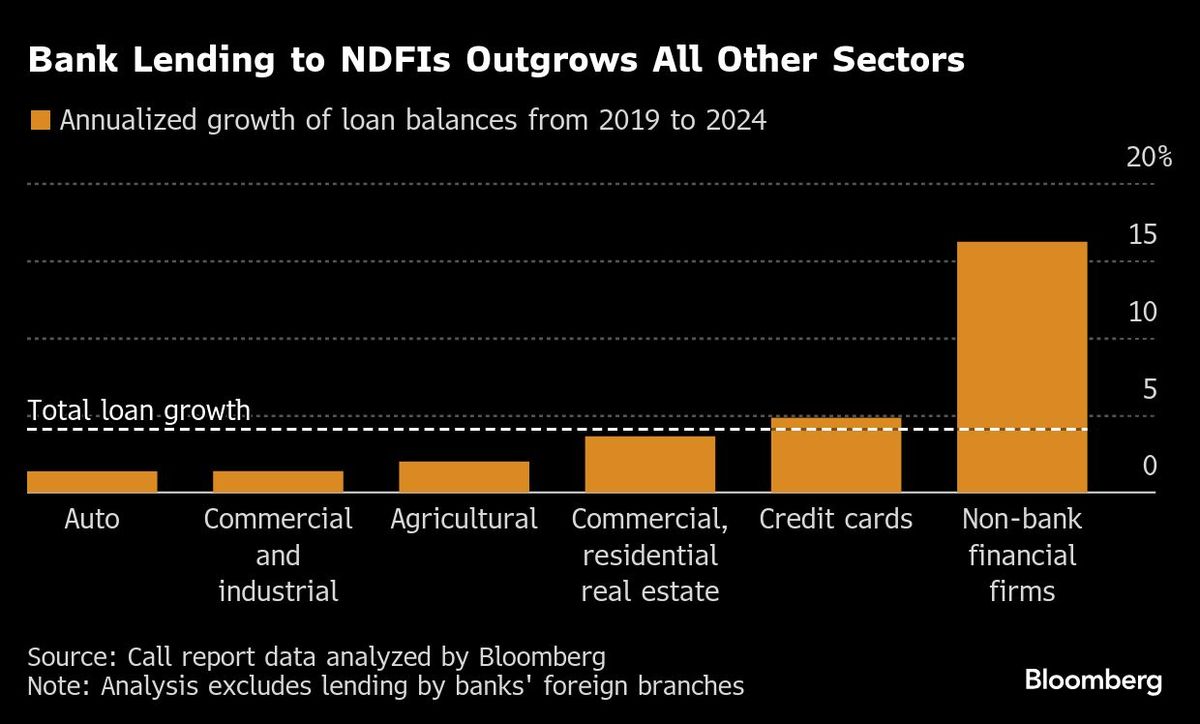

Traditional bank lending to non-bank financial institutions like private equity firms, hedge funds and private credit shops more than doubled in the past five years, according to data analysed by Bloomberg. That 16% annualised rate far surpassed their lending to categories including agriculture, credit cards, commercial and industrial companies as well as foreign governments, the data show.

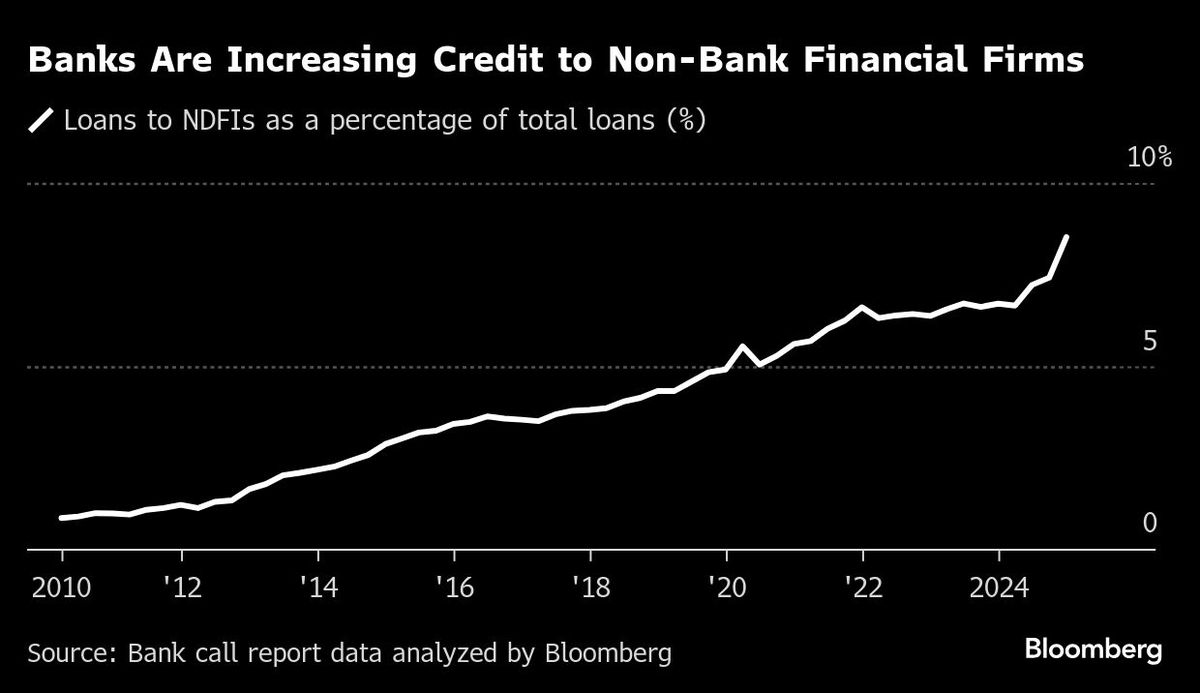

The phenomenon underscores the seismic shift taking hold in US finance, where less-regulated lenders have stepped into a void opened up after the financial crisis prompted banks to slow certain types of lending. As those firms proliferated, traditional banks eager to capture the spoils have gotten in on the action, with lending to companies often dubbed shadow banks hitting US$1 trillion (RM4.43 trillion) last year.

“The banks are caught in a weird dance,” said Brian Foran, who covers bank stocks at Truist Securities Inc. “In effect, banks are financing their own competition.”

Lending to non-depository financial institutions (NDFIs) — which also include mortgage lenders, student loan providers and real estate investment trusts — offers the prospect of additional revenue for banks, many of whom have been squeezed amid heightened competition for deposits. In theory, lending to such intermediaries partially shields the banks from the risk of any default by individual companies.

One Providence, Rhode Island-based lender says it’s benefitting from the shift. Citizens Financial Group Inc has more than doubled its roster of private equity customers to 175 since 2014, according to chief executive officer Bruce van Saun. Many of those clients expanded into private credit using financing from Citizens, which they lent to their portfolio companies, he said in an interview.

“We’re making more money from the growth in private credit than we’re losing in direct head-to-head competition with them,” Van Saun said.

Still, the increase in bank loans to NDFIs has long worried industry watchdogs. They’ve tried to get a better grasp on the risks, amid fears the deepening relationship could make banks more vulnerable to liquidity or credit shocks.

A report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston offers one glimpse into the rapid expansion. The 31 large banks that were stress tested last year committed about US$300 billion of loans to private credit and private equity funds in 2023, up from US$10 billion in 2013, the research shows.

In a recent step, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp (FDIC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Reserve started requiring banks to break out their exposure to NDFIs in more detail, citing the fast growth and heightened risks. Reporting methods “do not provide granularity on specific NDFI exposure, such as direct and off-balance sheet exposure,” among other information, the agencies said in a 2023 proposal seeking comment from the industry. Banks had to comply with the new rules for the first time earlier this year.

Bloomberg’s analysis of that data, gathered from the call reports of approximately 4,500 FDIC-regulated banks, showed their lending to NDFIs accounted for 8.5% of all their loans at the end of last year, up from less than 1% in 2010.

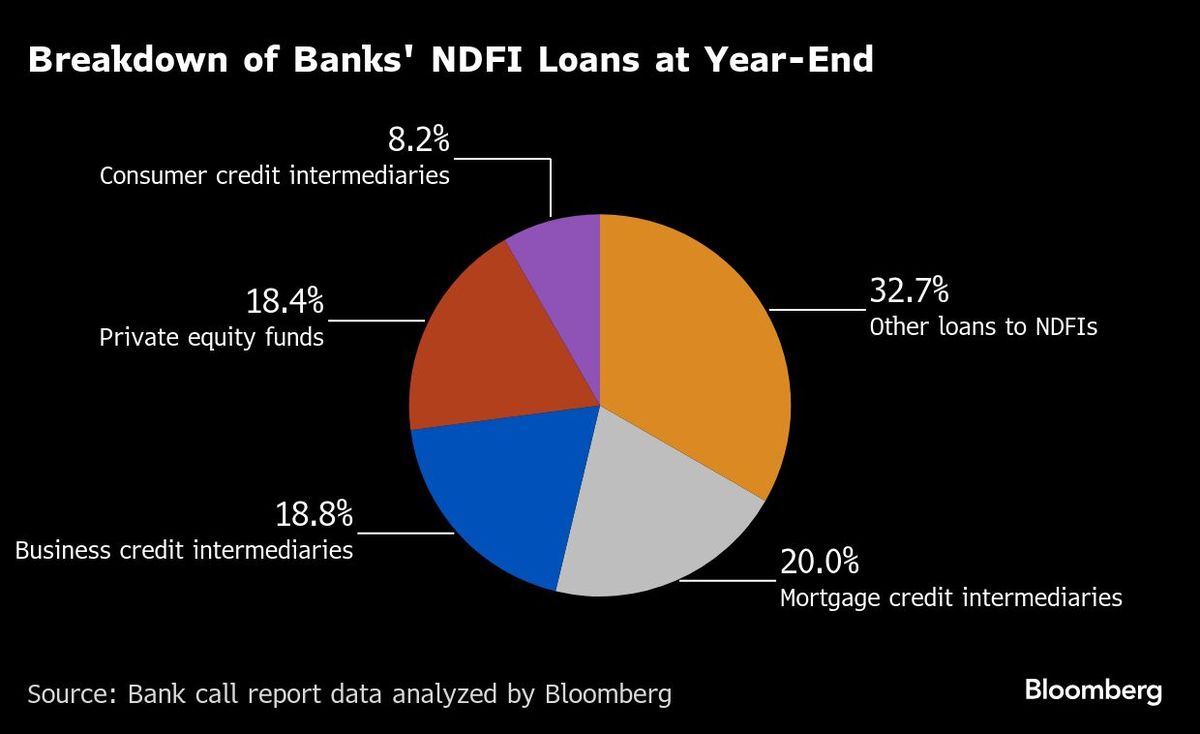

At the year end, mortgage lenders comprised about 20% of the pool while private equity firms borrowed about 18%. Almost 19% of the loans went to “business credit intermediaries,” a category analysts said should include private credit — a market that’s more than tripled to US$1.6 trillion over the past decade.

“Anecdotally, private credit is a big share of this pile,” said Chris Stanley, who leads the banking industry practice at Moody’s Analytics. “We’re at the start of a takeoff, not a landing.”

As the likes of Apollo Global Management and Blackstone Inc expand, the competition will only intensify. Non-bank lenders have often overtaken traditional banks as the largest source of corporate loans, particularly for midsized firms, Boston Consulting Group said in a report this month.

“It is hard to imagine banks gaining back the share lost, as the non-banks have become so entrenched,” Foran wrote in a note. “In C&I, private credit isn’t exactly two guys and a dog buying M&A flow from a PE firm, the large private credit players are increasingly organised like a bank with relationship managers and industry verticals and the like.”

In theory, non-bank lenders like private credit firms transfer risks outside the banking system, because they raise long-term funds from investors which match the duration of their loans, avoiding the kind of liquidity mismatches that flared up two years ago with the collapse of several regional lenders. But for private credit firms at least, a recent slowdown in fundraising may increase their reliance on bank loans, somewhat undermining the premise that such risks are safely kept at bay.

“The inevitability is that funding is going to keep coming from the banking system,” said Steven Kelly, associate director of research on financial stability at the Yale School of Management. “If it continues at its current pace, it will tip into risk-increasing.”

Classifying Loans

Even with the new rules requiring more detailed classification of NDFI loans, the data remains a little difficult to parse. Muddying things are how banks chose to classify their loans: It’s not entirely clear what the business credit intermediaries category — the recipient of US$196 billion of bank loans — contains. There is an “other” category to which the banks allocated the biggest chunk, or 33% of their non-bank loans. In fact, JPMorgan Chase & Co. assigned all US$114 billion of its NDFI loans to that group, while PNC Financial Services Group, with US$23 billion, did the same.

Representatives for JPMorgan and PNC declined to comment.

All the banks have a two-quarter grace period to report the data on a best effort basis and will have to report NDFI data “comprehensively” from the end of June.

However the data is sliced and diced, the expansion of NDFI lending is clear, according to Terry McEvoy, analyst at Stephens Inc.

“Higher capital requirements and growing regulation within the banking sector contributed to NDFIs stepping in and absorbing loan demand,” McEvoy wrote in a note last month. “Less regulation and faster adoption of emerging technology have also led to outsized growth in NDFIs.”

In another bid to understand the risks, the Fed has tacked on a requirement to the annual stress tests, a set of exams which simulate how banks respond to adverse shocks. It has asked how banks would respond to credit and liquidity shocks from the non-bank sector, and they have to simulate a scenario where their five largest equity hedge fund counterparties experience unexpected defaults.

While such a grave scenario hasn’t come to pass, market swoons like the recent one can put investors on edge. If a rout morphs into a sustained slump, asset price declines can trigger margin calls forcing investors to step up more collateral and, at the more extreme end, liquidate their holdings at a discount. That forced selling can spiral — and banks now have a deeper connection to those players.

Some have similar concerns about counterparty risks that the private credit sector could pose to banks.

“This market exists for a reason,” said Jeff Davis, a managing director at Mercer Capital. “But it hasn’t been truly tested in a downturn.”

Uploaded by Felyx Teoh

- China's biggest state banks to raise US$71.6b to boost capital

- Japan to give crypto assets legal status as financial products, Nikkei says

- Four Chinese nationals detained for illegally entering Bangkok disaster zone to 'retrieve documents'

- Gold rises to record as trade-war concerns drive haven demand

- Volvo Car brings back Samuelsson as CEO to steer turnaround

- King, Queen perform Aidilfitri prayers at Federal Territory Mosque

- Asia braces for historic test of export model from Trump tariffs

- Temasek-backed 65 Equity makes European foray with Swiss pharma merger

- Trump won’t rule out seeking third term as US president, says there are ways

- Trump threatens Russian oil penalties in bid to persuade Putin to accept ceasefire