(March 27): Indonesia is betting on tiny bugs from Africa to help boost its palm oil production, as the broader sector grapples with tightening supply that threatens to keep prices elevated and add to food inflation.

The world’s top grower is planning to introduce around one million of the weevils at some plantations this year to improve pollination and fruit development. Three species collected from Tanzania are expected to arrive at a facility in North Sumatra next month for a series of tests, before they are released.

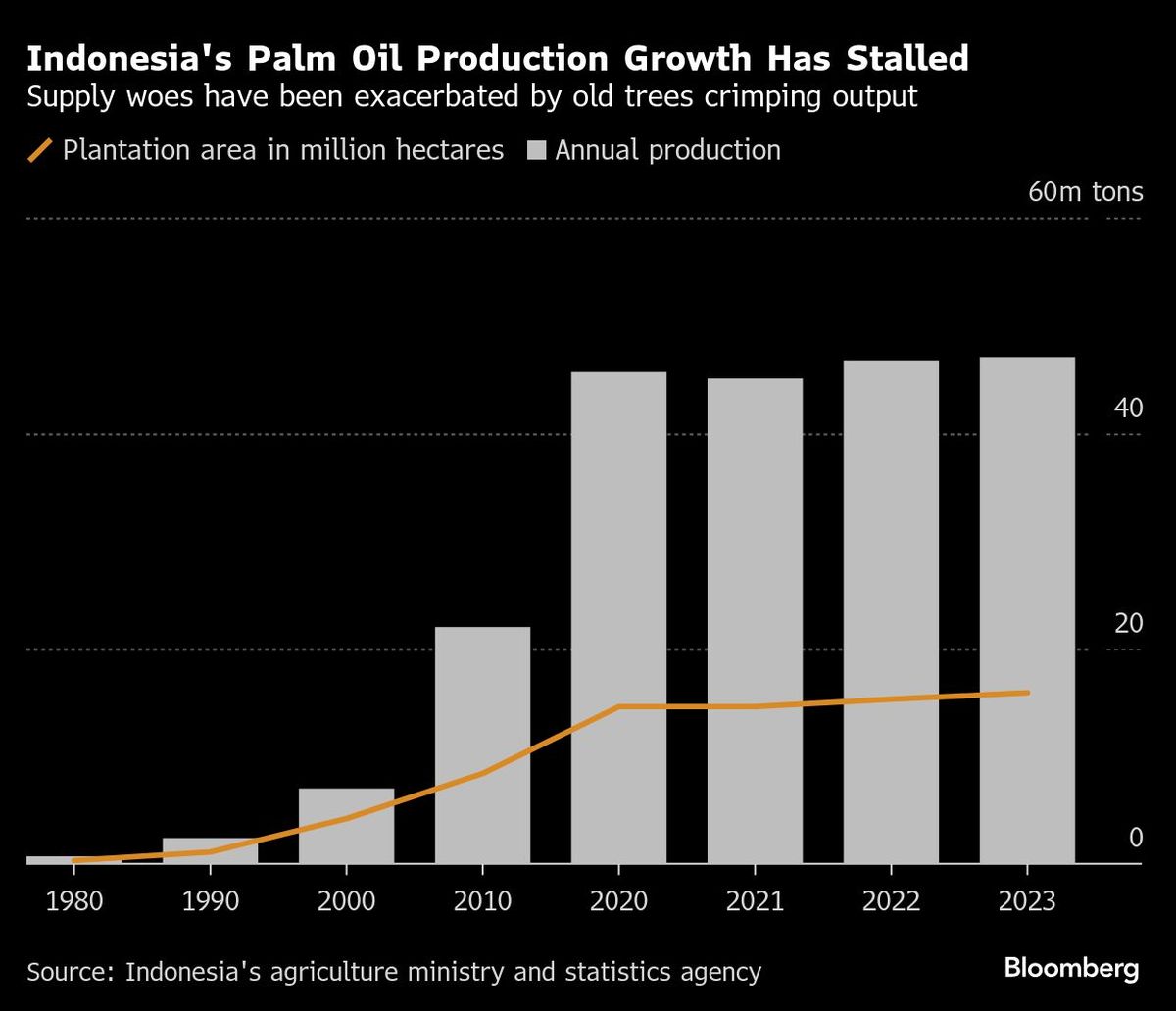

The hope is that the African weevils will help revive production growth after years of stalling output, which stems from old trees that some growers are reluctant to replant due to the extended time it takes for them to fruit. Constrained supply, including from the second-biggest producer, Malaysia, has contributed to palm relinquishing its status as the world’s cheapest vegetable oil to soyoil.

Adding to the problem: Indonesia now wants to expand its biofuel programme, meaning more palm oil will be diverted to local supply rather than used for export. That has put the insect initiative at a crucial time.

‘Fresh batch’

Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s palm industries have ballooned over recent decades, often at the cost of large swathes of native jungle and forests. The two now account for around 85% of global supply of the most widely used vegetable oil, which can be found in products from chocolate to cosmetics and biofuel.

Palm oil is native to Africa, making the Tanzanian bugs well suited for the role, and an insect release has been successful in the past. Weevils were introduced during the 1980s to plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia, leading to significant improvement in production rates.

“We need a fresh batch of the insects,” said Dwi Asmono, the head of research and development at the Indonesian Palm Oil Association, known as Gapki. The industry group is leading the initiative with support from the government, and state-owned and private producers.

“It’ll be like having a troop of free workers to pollinate the flowers,” he added. “Some of the factors to be studied before a wide release are their enemies, friends, and their behaviour in the morning, day, and night.”

A team of Indonesia researchers collected around 6,000 weevils in Tanzania in January, which will be sent to the North Sumatran lab owned by the Indonesian Oil Palm Research Institute. A task force including entomology experts and the Biosafety Commission will study the insects and their interaction with local species before they’re released at plantations.

The weevils will reproduce in vast numbers at the facility before being given to about 20 companies that are part of the initiative, according to Gapki’s Asmono. The agriculture ministry will decide on the next steps including the potential for wider distribution following the trial, he added.

“We expect it could significantly increase national palm oil production,” said Dwi Sutoro, a director at state-owned plantation company PT Perkebunan Nusantara III (Persero), which is taking part in the programme.

The insects are from the Elaeidobius genus of palm-pollinating weevils, which are around, or slightly bigger than the size of a pinhead. They have a large capacity to transfer pollen and are highly host-specific to palm oil trees.

The weevils offer growers a faster fix to their supply woes, but they risk distracting from the urgent need to replace old plantations that are no longer producing at their peak. New trees start bearing fruit at three years, whereas the insects can yield bigger bunches within 12 months.

“The initiative is a solution for young palm trees,” said M. Hadi Sugeng Wahyudiono, a director at Astra Agro Lestari, a palm producer participating in the insect trial. “Older ones, especially those over 25 years old, need to be replanted using high productivity seedlings.”

Indonesia released about 500 weevils back in the 1980s, with studies showing successful fruit formation on palm oil trees increasing to 75% from 40%. Gapki predicts the new batch of bugs can lift that to at least 85%.

Still, weevils are not the only factor determining a successful harvest. High quality plant varieties, adequate volumes of fertiliser and proper agriculture practices are also vital for maintaining or raising palm oil production, while pests and diseases remain a constant threat.

Uploaded by Liza Shireen Koshy

- Authorities urge vigilance, calm after 5.4 magnitude quake hits Indonesia’s Banda Aceh

- Insolvency DG warns of rising trend in self-declared bankruptcy

- 5.1-magnitude aftershock hits north of Mandalay amid series of quakes — USGS

- Young man rescued from Cambodia job scam repatriated to Malaysia

- Myanmar quake death toll hits 1,700 as aid scramble intensifies

- Unity must be preserved with utmost care, says King, Queen in Aidilfitri message

- Myanmar quake death toll hits 1,700 as aid scramble intensifies

- Muslims in Malaysia celebrate Aidilfitri tomorrow

- Foreign minister to undertake humanitarian mission to Myanmar, express Malaysia’s solidarity

- Balloon seller scuffle: Police open three investigation papers