Katsunori Tanaka on March 4, 2025.

(March 25): Katsunori Tanaka spent most of his 19 years at Goldman Sachs Group Inc scrutinising Japan’s biggest banks as an equity analyst. Now, he’s making money obsessing over much smaller lenders at his 48 billion yen (US$320 million, or RM1.42 billion) hedge fund Ariake Capital.

Tanaka’s switch centres on investing in banks whose businesses barely extend beyond the Japanese countryside — lenders that until recently were dismissed as the embodiment of the country’s decades of stagnation and deflation. Now, with prices and interest rates trending higher for the first time in a generation, things are finally looking up for the sector, even as economic prospects in many rural areas remain uncertain.

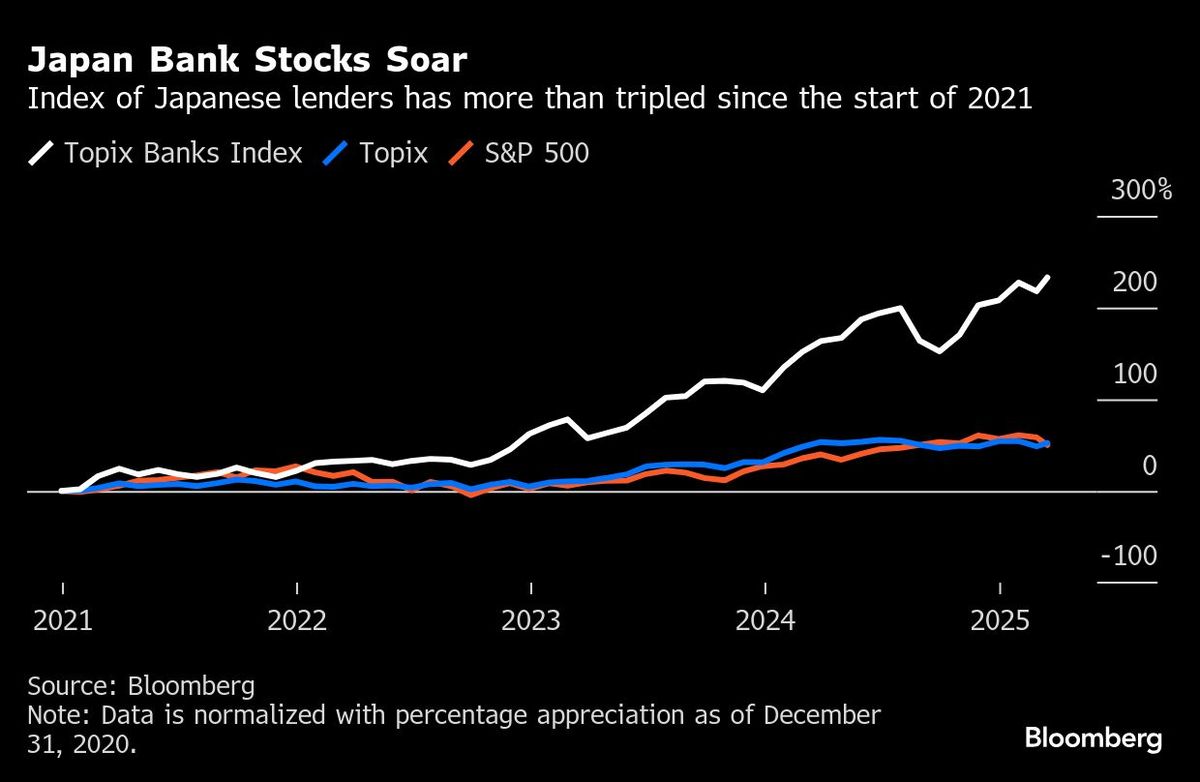

It’s been a success so far, with the fund returning more than 300% in roughly three years since its inception. Ariake recently raised money from family offices in the US, underscoring how global investors’ renewed interest in Japan has extended to money managers who can generate returns beyond the obvious targets.

“We took a very unique strategy, so it can’t be easily copied by bigger firms,” Tanaka, the 49-year-old chief investment officer at Ariake, said in an interview. “Regional banks are a sector that is not attracting attention in the stock market in Japan, and there is an upside there.”

Good timing has helped — the Bank of Japan ended its eight-year experiment with negative rates in early 2024, boosting financial stocks broadly. Even so, his fund beat the Topix Banks Index’s 158% gain and the Nikkei 225 Stock Average’s 43% advance since Ariake started trading in late 2021 through to December.

“I was lucky,” Tanaka said, speaking from a shared office facility where he runs Ariake’s eight-person operation in Tokyo’s Kabutocho district, steps away from the Tokyo Stock Exchange. “I’ve been blessed with a very good period in time.”

Putting aside the initial gains, Tanaka said the next five years are when his thesis will be tested. Ariake’s strategy, as he puts it, is “friendly” activist investing. The fund — which also counts wealthy Japanese individuals among its investors — wagers on local banks that intend to improve their business and stock price in the new era of positive interest rates.

The broader bet is that the regional banks selected by Tanaka will have higher-caliber managers who are willing to pursue mergers and new business strategies. They will also be keen to sell stakes in client companies and use the proceeds for more productive ventures, he said.

Ariake’s current portfolio is about 10 holdings, not all of which are disclosed publicly. They include a 19.9% ownership in Chiba Kogyo Bank Ltd, east of Tokyo; and 1.53% in Yamanashi Chuo Bank Ltd, west of the capital city, public documents show.

Still, the landscape is tough: Ariake’s investable universe is fewer than 100 listed lenders with market capitalisations at a tiny fraction of megabanks like Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc. They operate in areas of Japan with dwindling populations and economic outlooks that typically spell doom for banks whose main function is lending to local growing businesses. Even if banks wind down their cross-shareholdings, there are questions over how they can spend the proceeds in a way that spurs profitability.

“The fate of the regional banks is really dependent on the regional economy,” said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Hideyasu Ban. Ariake “has to have a certain performance in a certain period of time, but sometimes, corporate value creation can take five years, or 10 years, or longer.”

One of the few ways that local banks can grow is by combining with each other. Unlike their larger peers in Tokyo, they lack the vast financial resources required to expand abroad.

In past years, numerous calls for regional lenders to consolidate, even by regulators and politicians, have led to only sporadic action in a country that is widely seen as overbanked. Japan has 33 bank branches per 100,000 people, compared with 26 in the US, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Although the exit from negative rates has helped Ariake’s returns, it may now provide a challenge by stalling any momentum for reform. “With higher interest rates, at least some weaker banks are feeling relief,” said Kiyoko Ohora, chief analytical officer for S&P Global in Japan. “The motivation for weaker banks to merge is lower because of higher interest margin.”

Tanaka disagrees. He expects inflation, which has stayed above 2% for almost three years, to help him. “There’s an incentive for weak banks to go after economies of scale to control costs in an inflationary world,” he said. “Weak banks generally have high cost ratios, so they will also have an incentive to engage in M&A (merger and acquisition).”

Ariake’s performance will also depend on other investors buying into regional bank stocks, some of which aren’t traded frequently, making it tricky to exit without disrupting the market.

Years of negative rates have made Japan a tough market to invest in, said David Atkinson, the former chief banking analyst at Goldman Sachs, who oversaw the division Tanaka was in. “They’re dealing with the consequences of that,” said Atkinson, who remembers the Ariake founder as being skilled at data analysis. “If Tanaka can find a way of making money out of understanding that situation, all the better for him.”

Tanaka’s process is simple and analog: he relies on his knowledge and relationships accumulated from analysing banks at Goldman, where he rose to managing director. He still prioritises building ties with the banks through regular face-to-face meetings. That means he needs to be in Japan for his strategy to work, unlike the many Japanese hedge fund founders who have chosen to base themselves in Singapore.

He has already claimed some wins. One of Ariake’s early stakes, Hokkoku Financial Holdings Inc, which runs about 100 branches mostly in Ishikawa prefecture by the Sea of Japan, halved its strategic shareholdings in the past three years, and aims to eventually dispose of everything. Shizuoka-based Suruga Bank Ltd, which Ariake built a more than 5% stake in, according to a filing, has also said it seeks to reduce its cross-shareholdings.

Representatives for Suruga declined to comment. Hokkoku said it had already been considering its mid-term plans and strategy for strategic shareholding. The bank said Ariake advised it on presenting its plans to investors.

Tanaka said his father, a well-known economic critic, helped him nurture an independent streak in his youth. He joined Goldman in 2001, after graduating from Keio University — a time when it was still seen as risky to join a foreign company and most top-tier graduates opted to become government officials. When he left Goldman in 2020 to strike out on his own, he drew on that same sense of freedom.

“Finally, I got my independence,” Tanaka said, adding that he would never join a hedge fund platform or larger investment firm. “Our style is a long-only engagement fund for a specific sector. We’re not normal, we’re a unique fund.”

Uploaded by Liza Shireen Koshy

- US seeks to control Ukraine investment, squeezing out Europe

- US beef sales to China skid after Beijing lets export registrations lapse

- HI Mobility debuts on Main Market with slight premium

- Iran oil-filled tankers build up off Malaysia as US sanctions mount

- Tesla’s US$14b rally eclipses rout in other auto stocks

- American banker on trial says innocent verdict will help Japan

- Sarawak Cabinet approves free tertiary education for 2026 implementation

- Deutsche Bank extends CEO's mandate and revamps board in crucial year

- Japan's Nikkei ends at two-week low as automakers slump on US tariff worries

- Thailand targets reduction in US trade surplus to US$20b