(Graphic by Freepik/Vecteezy)

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 17, 2025 - March 23, 2025

MALAYSIA imposed a movement control order (MCO), or Perintah Kawalan Pergerakan, on March 18, 2020 — a week after the World Health Organization declared the Covid-19 outbreak a global pandemic. The measure was taken to curb the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19.

Initially set for two weeks, the MCO was extended three times until May 3.

Subsequently, there were various iterations of the MCO as infections rose with the emergence of more virulent strains of the virus, resulting in more infections and deaths.

As at March 8, 2025, a total of 37,351 people in Malaysia had lost their lives to the virus. Globally, the number stood at 7.1 million as at Feb 23, 2025.

In those initial days of the MCO that dragged into weeks and months, it was hard to imagine what a post-Covid world would be like. Looking back, the period in lockdown was a dystopia that many prefer to forget, but it stands out as a collective shared experience globally, as almost the entire world was forced to stay home.

With movement restricted, malls, restaurants, theatres, sporting venues and even places of worship emptied out. As it was established that the virus spread through close person-to-person contact, the number of people at gatherings was restricted here, as was the case elsewhere.

Sanitising became a standard requirement and masking was a must. Those found not wearing a mask in public risked a compound of RM10,000. Unlike in Western societies, most Malaysians obediently put on their masks.

The pandemic created a whole new range of data sets to help monitor the spread of Covid-19. Infection and death rates were announced daily by the then director general of health Datuk (now Tan Sri) Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah and published on theedgemarkets.com. That the disease came in waves was made clear as he told Malaysians on his broadcasts to stay home to help “flatten the curve”.

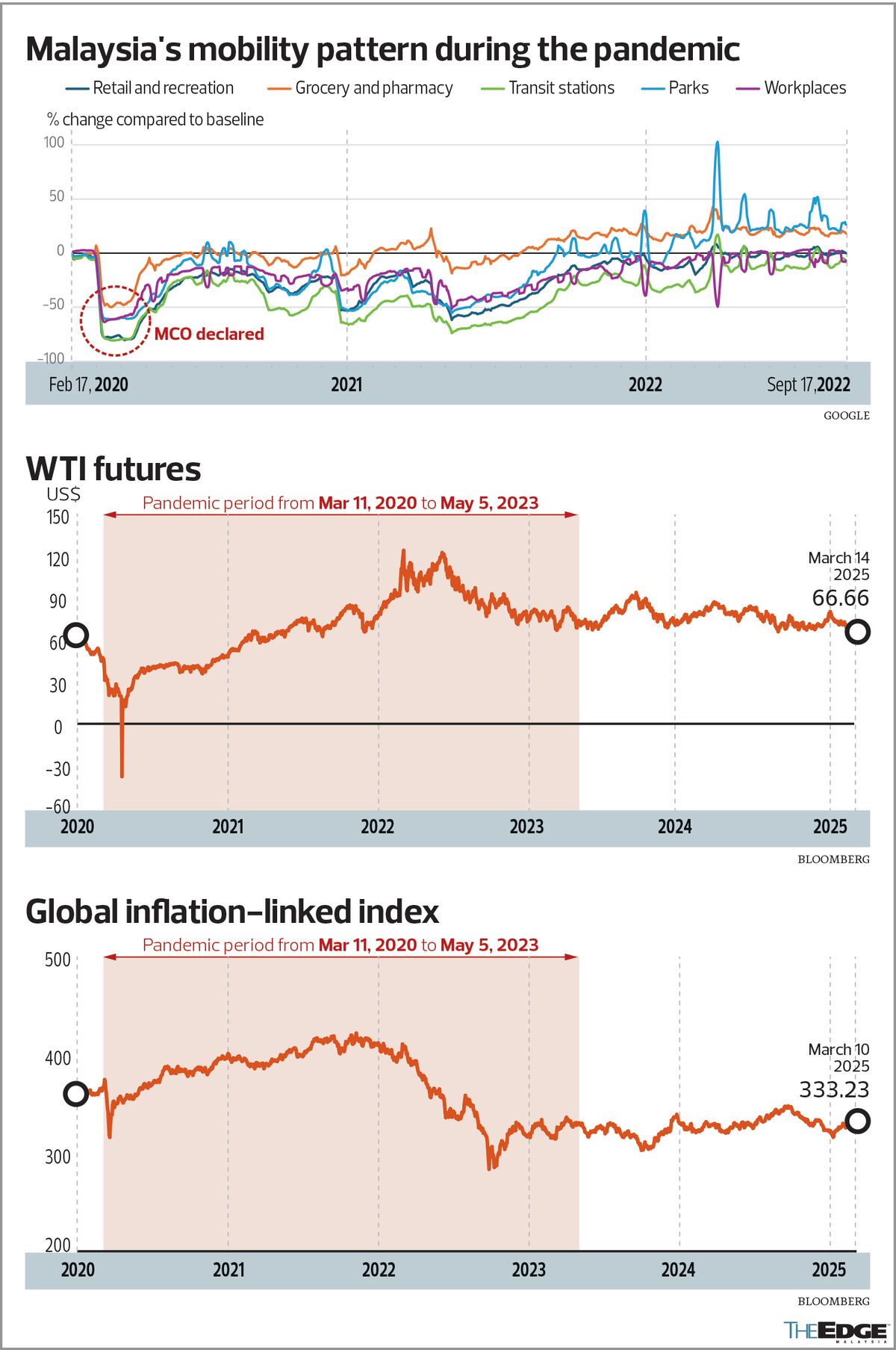

Google came out with its Community Mobility Report to help public health officials in their decision-making in the battle against the virus’ spread. Malaysia’s mobility report shows movement plunging from March 2020 onwards (see chart).

With travel and economic activities halted, many other indicators crashed as well. Oil prices dropping to negative territory was the most dramatic as storage facilities to hold the crude that nobody wanted soon ran out of space. On April 20, the one-month contract for West Texas Intermediate plunged from US$18 a barrel to -US$37 a barrel.

Other commodities followed and stock prices cratered.

Companies adopted a work-from-home (WFH) policy during the pandemic and it remains in place in various places.

“WFH has already peaked because it’s unsuitable for many businesses, but for some vocations or areas, it is ideal. So, hybrid WFH is here to stay,” says a business consultant who requested anonymity.

Stuck at home and with time and money on hand, many young first-time investors flocked to equities, which helped push glove and vaccine stocks into stratospheric territory.

Then came the supply chain shocks. This, and the rising demand for goods from people stuck at home, contributed to global inflation.

When Covid-19 vaccines were rolled out, the race to get people vaccinated became a priority, as it offered a clear pathway out of the pandemic. Naturally, vaccination rates of countries were closely monitored and Malaysia made news briefly for having one of the highest rates in the world.

Five years on, we can surmise that some predictions came true while others were off by a mile, but that is understandable, given the unprecedented nature of the pandemic.

A prominent change that has stuck is the digitalisation of our lives — in the way we shop, communicate and get things done.

“Online shopping has taken away market share from certain retail categories, but that was expected. We reckon most department store business models are just surviving because of their loyalty programmes. F&B and services are rebounding, but that’s simply because you can’t experience that at home.

“Digital payments continue to grow and, now, governments are pushing e-invoicing. These trends were inevitable, but the pandemic response has made it easier to push changes. I don’t think most people will remember Covid’s impact as a major driver in accelerating these changes,” the business consultant adds.

The pandemic was also deeply divisive in many ways. The phrase “dua darjat” came to prominence during this time, referring to the exemptions from harsh Covid-19 rules given to the ruling class and elite while the rest of the population paid the price for flouting them.

Meanwhile, those with jobs in essential sectors that were less affected by the lockdowns or who had sufficient reserves stayed safe at home while those with no savings, or were freelancers or worked in the services industry that was hardest hit by lockdowns, had to turn to the government for help or take on jobs as delivery riders.

The vaccination drive also brought anti-vaxxers out into the public space with their refusal to take the mandatory vaccines, further dividing communities.

Amid all this, the country’s political instability also weighed on the people, who were already suffering immensely on all fronts.

The government then under Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yasin had emphasised that fighting the virus would take a whole of society approach. The #benderaputih — or white flag — movement that coalesced from efforts undertaken by ordinary folks to help those in distress was one such response.

Businesses and corporations stepped in to help too. The Edge Media Group set up The Edge Covid-19 Health Care Workers Support Fund to aid affected healthcare workers and helped raise over RM25 million to support the country’s pandemic efforts.

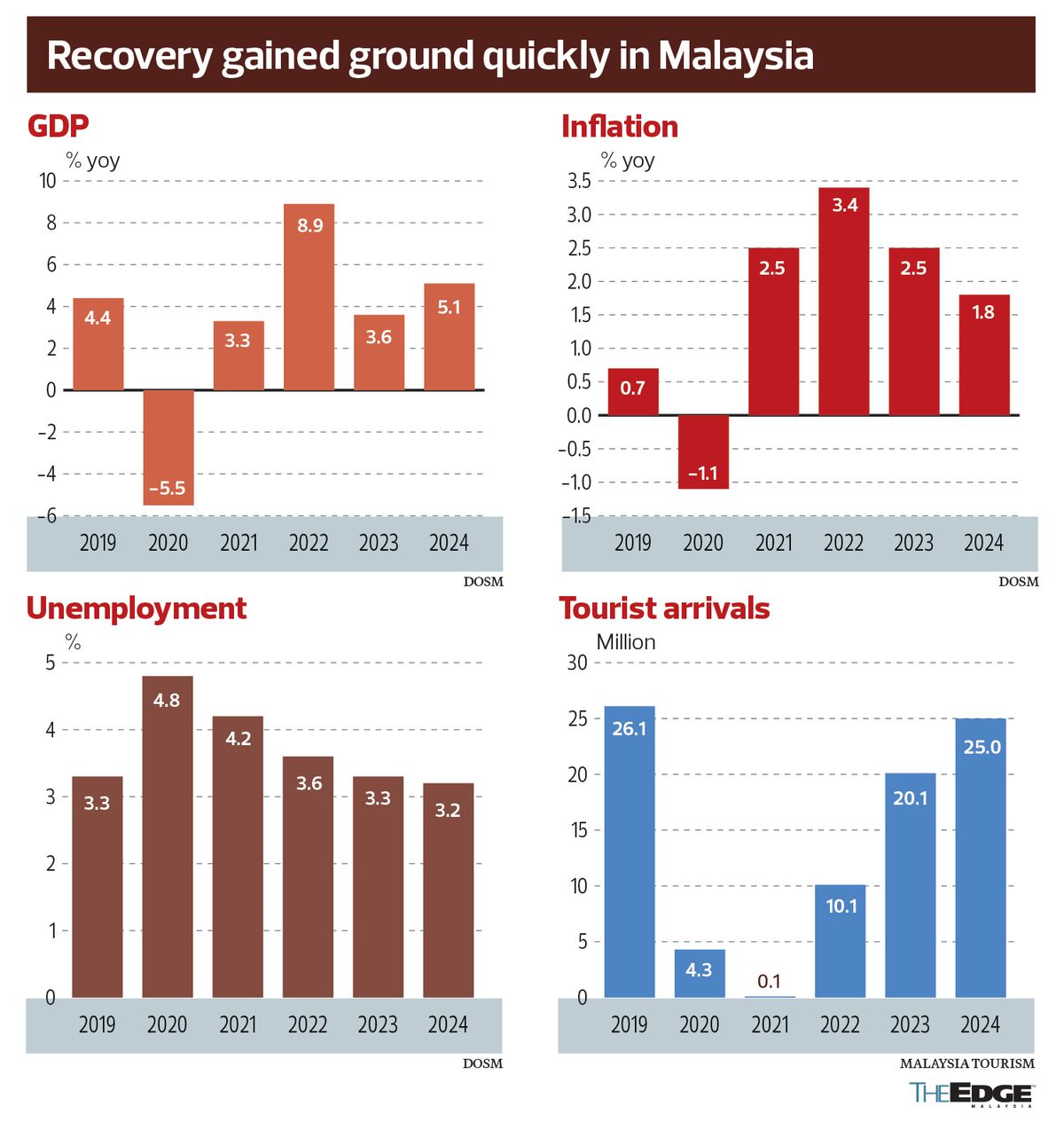

The recovery from the pandemic, while hesitant at first, gained ground quickly, with many sectors having returned to pre-pandemic levels. The crowds came back, inflation picked up and the post-Covid travel boom remains strong, although tourist arrivals still lag the 2019 figures for Malaysia.

What will be the lasting impact of the pandemic, a once-in-a-century event?

When asked this question, economist and executive director of the Association of Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia’s Socio-Economic Research Centre, Lee Heng Guie, says it is the millions of lives lost due to the virus, the human suffering caused by job instability and poverty, and the loss of educational opportunities as schoolchildren had to learn remotely but were hampered by the lack of internet facilities.

“It’s [also] the illness from long Covid, the deleterious mental health effects, the digital transformation to make living, working and doing business easier,” he adds.

Read also:

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- World Economic Forum highlights EPF as model for sustainable retirement reform

- Li Ka-shing's CK Hutchison mulls global telco assets spin-off, eyes London listing, Reuters reports

- U Mobile secures MCMC award, gears up for nationwide 5G roll-out

- Indonesians feeling market gloom ahead of major holiday

- Seeking opportunities in a risk-off market

- Trump pressing advisers for tariff escalation ahead of April 2, Washington Post reports

- Myanmar's quake toll passes 1,000 as extent of devastation emerges

- MetMalaysia can issue quake warnings within eight minutes, says DG

- Li Ka-shing's CK Hutchison mulls global telco assets spin-off, eyes London listing, Reuters reports

- Vance accuses Denmark of not keeping Greenland safe from Russia, China