This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 17, 2025 - March 23, 2025

IF a 6.3% dividend from the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) for 2024 did not provide enough “feel good” factor this side of the Causeway, the positive vibe probably went up after a Singaporean personal wealth mentor said Malaysians are “sitting on a gold mine called the EPF” with “insanely high” returns that Singaporeans “would drool” over.

Pointing out that Singapore’s Central Provident Fund (CPF) ordinary account offers only 2.5% returns per annum, with a 4% rate only applicable to the more restrictive Special and Medisave Accounts, Loo Cheng Chuan, founder of the “1M65 (saving S$1 million by age 65) movement” who advocates saving early and living frugally, said in a YouTube clip last week that “people underestimate the power of compounding [interest]”

“Let’s say the average return is about 6.5% [per year]. If you compound [that] over 35 years … If you put in 100,000 dollars [at age 30], it will become 900,000 dollars by the time you turn 65,” Loo said in the interview “Do More — Take Charge of Your Life”, which was picked up by several local media last week and was widely shared on social media.

While the “CPF millionaire” rightly pointed out the difference in the long-term compounding power between an interest rate of 2.5% per annum and 6.5% per annum as something more Malaysians should be taking advantage of, Malaysians should not immediately dismiss the merits of the Singapore CPF system, particularly reforms undertaken to ensure more people have a steady income stream upon retirement. More on this later.

Compounding power

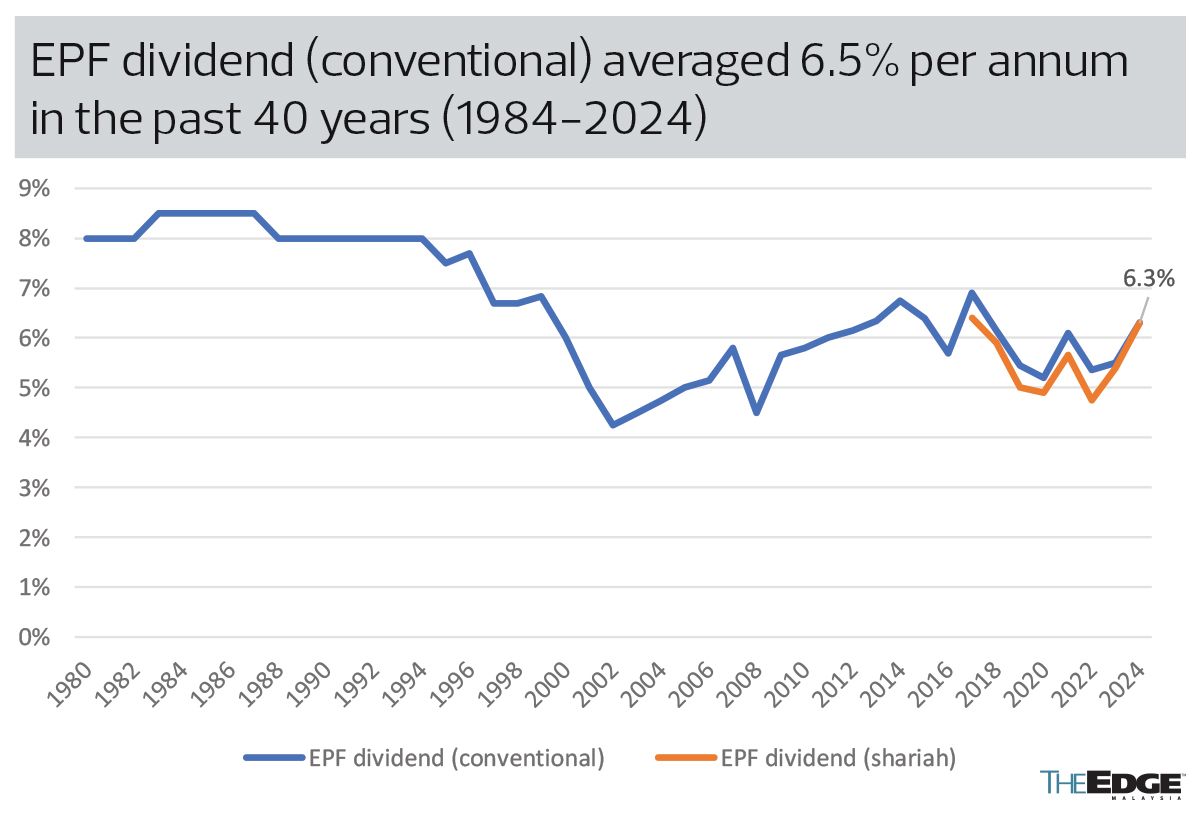

That 6.5% dividend rate used in the example looked high at a glance because the EPF’s annual dividend had actually averaged 5.98% per annum in the past 10 years (2014-2024), 5.76% in the past 20 years (2004-2024) and 5.9% in the past 30 years (1994-2024).

If one were to look at the EPF’s annual dividends in the past 40 years (1984-2024), however, the average would be 6.5% — thanks to EPF dividend rates being above 8% between 1980 and 1994, during which time 12-month fixed deposit rates even went above 10% per annum, according to data from the EPF and Bank Negara Malaysia.

A savings of RM100,000 compounded at 6.5% per annum would double every 11.1 years and yield just over RM900,000 after 35 years.

If you had deposited RM100,000 into EPF at age 30 in 1990 and allowed that amount to compound untouched over 35 years, you would today have just over RM790,000 saved with the EPF at age 65, based on The Edge’s back-of-the-envelope calculations using actual EPF annual dividends. That is, of course, if you did not take out the RM450,000 it had grown to after 25 years at age 55 in 2015.

Even at 5% per annum, a savings of RM100,000 would double every 14.4 years to just over RM550,000 if allowed to compound untouched over 35 years.

Currency strength

At a return of 2.5% per annum, it would take 28.8 years for savings to double.

Someone who had saved S$100,000 at the age of 30, and allowed it to compound over 35 years at a rate of 2.5% per annum, would only have just over S$237,000 by the time he or she reaches age 65.

Even though the median monthly wage in Malaysia of around RM2,745 is much lower than Singapore’s median monthly wage of S$5,500 (including CPF contributions), Loo reckons that the strong compounding potential from a high EPF dividend rate makes up for lower wages among many Malaysians.

Nonetheless, he acknowledged the strength of the Singapore dollar against the ringgit.

To be sure, the difference between S$237,000 (from 2.5% return per annum) and S$900,000 (from 6.5% return per annum) is stark.

If one were to look at the 35-year period between 1990 and 2024, the ringgit had depreciated against the Singapore dollar from 1.4283 at the start of 1990 to 3.4817 by the start of 2024 before retracing to 3.2744 at the start of 2025, according to Bloomberg data.

So, even when compounded at just 2.5% per annum over 35 years, a S$100,000 (RM143,830) savings in 1990 would today grow to S$237,321 — which translates into between RM783,158 and RM830,622, assuming an exchange rate of S$1 to between RM3.30 and RM3.50.

If each Singapore dollar fetches more than RM3.33, the ringgit equivalent of S$237,321 (S$100,000 compounded at 2.5% per annum over 35 years) would exceed the savings pool of RM790,336 (RM100,000 compounded using actual EPF dividend over 35 years between 1990 and 2024), simple workings show.

Necessary reforms

This is not to dismiss the EPF’s stellar dividends when stacked against the Singapore dollar’s strength.

While EPF dividends are indeed enviable, so much so that expectations have built up over the decades, the law only guarantees 2.5% returns per annum for conventional savings. Internally, the EPF aims to preserve and grow its 16 million members’ retirement savings by having annual returns that beat inflation by at least 2% over every rolling three years.

To borrow the words of EPF CEO Ahmad Zulqarnain Onn during a recent interview with The Edge, the provident fund believes that “80% of the returns that EPF members get over a sustained period of time” is driven by the stringent decision-making process that goes into deciding its strategic asset allocation mix, which is refreshed at least every three years.

He, for one, thinks Malaysia should have a deep conversation on the necessary reforms that need to happen so that more Malaysians would have a steady income stream when they hit retirement age.

For one, there is great reluctance to align the current EPF withdrawal age of 55 with the retirement age of 60, even though the EPF withdrawal age of 55 was set at a time when the average lifespan of Malaysians was around 60. Today, Malaysians live past the age of 76, on average, and EPF research shows most members exhausting their retirement savings after five years.

To prevent CPF members from exhausting their retirement savings too quickly, Singapore decided more than 35 years ago that the members could only withdraw amounts in excess of a minimum savings, which it progressively raised over the years to keep pace with inflation. Taking into account savings adequacy and the longevity of Singaporeans living past age 85, the CPF payout age had also increased from 55 to 60 to 65 — something that sparked pushback from members who were unhappy about the government locking up the people’s money for longer. With time, more people have come to understand the rationale of the change.

Ahmad Zulqarnain also told The Edge that Malaysia needs to transition EPF from a provident fund that allows full lump-sum withdrawal upon retirement to one that allows partial withdrawal plus a steady income stream.

“CPF has shifted over time, over two phases, where initially it was a certain portion of your savings that can be withdrawn on a schedule, not with a lump sum. And then subsequently, they then introduced something called CPF Life, which is the annuity. So irrespective of how long you live, you get that stream. Starting point matters, and transitioning is not so easy but we have to figure out, how do we transition to this system,” he said, referring to the annuity scheme which started out as a voluntary opt-in scheme for CPF members but since 2013 has become mandatory for all born in 1958 and after and have enough savings for a lifelong monthly pension.

Unlike Singapore, where CPF is compulsory for all Singapore citizens and permanent residents, EPF statutory contributions are only applicable to private sector wage earners in Malaysia. Some 40% of Malaysians are not covered by any retirement schemes, with only 50% covered by the EPF and another 10% by the government’s defined-benefit pension scheme for civil service retirees.

And unlike Singapore, which only requires CPF contributions up until a certain wage ceiling (which is being gradually raised from S$6,000 per month in 2023 to S$8,000 by 2026), there is no wage ceiling for statutory EPF contribution rates.

This means that those with higher wages and can save more money with the EPF are able to benefit even more from the EPF’s high dividend rates, given the proportionately higher savings. That the EPF’s total assets is already over RM1 trillion, with some 80% of the money it receives every year being invested within the country, means the EPF has become an integral part of the economy. Members with savings above RM1 million (RM1.3 million by 2028) are free to withdraw amounts in excess of that threshold at any time, regardless of his or her age. This is probably another source of envy for millionaires across the Causeway.

Considering the burden on public finances should many people not have enough retirement savings at old age, Malaysians may not be the one with the last laugh if the necessary retirement reforms do not happen.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- World Economic Forum highlights EPF as model for sustainable retirement reform

- Li Ka-shing's CK Hutchison mulls global telco assets spin-off, eyes London listing, Reuters reports

- U Mobile secures MCMC award, gears up for nationwide 5G roll-out

- Indonesians feeling market gloom ahead of major holiday

- Seeking opportunities in a risk-off market

- Indonesian Muslims to celebrate Eid on Monday

- Myanmar hit by fresh 5.1 aftershock, tremors felt in neighbouring countries

- Myanmar's quake toll passes 1,000 as foreign rescue teams arrive

- Trump pressing advisers for tariff escalation ahead of April 2, Washington Post reports

- MetMalaysia can issue quake warnings within eight minutes, says DG