This article first appeared in Forum, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 17, 2025 - March 23, 2025

With a combined GDP of over US$3.8 trillion (RM16.8 trillion) and a population exceeding 670 million, Asean stands as one of the fastest-growing economic blocs globally. Yet many of its members are small, open economies heavily reliant on international trade and investment to drive economic development and growth. Globalisation has propelled the region forward by enabling these nations to specialise in goods and services where they have a comparative advantage and are provided access to markets outside of their own country. Thus, the recent resurgence of US trade protectionism has understandably sparked renewed calls for building resilience within Asean.

When US President Donald Trump restarted his trade war — targeting a broader spectrum of key trading partners with potentially steep tariffs — the turbulence in the global trade landscape underscored the urgency of recalibrating Asean’s trade strategy. Enhancing trade integration within the region appears to be the go-to approach. It is a logical one, especially given that intra-Asean trade currently accounts for only about 22% of the region’s total trade despite the near-elimination of tariff barriers under the Asean Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2010. By contrast, intra-EU trade represents around 60% of total trade, highlighting the unrealised potential of the Asean Economic Community blueprint.

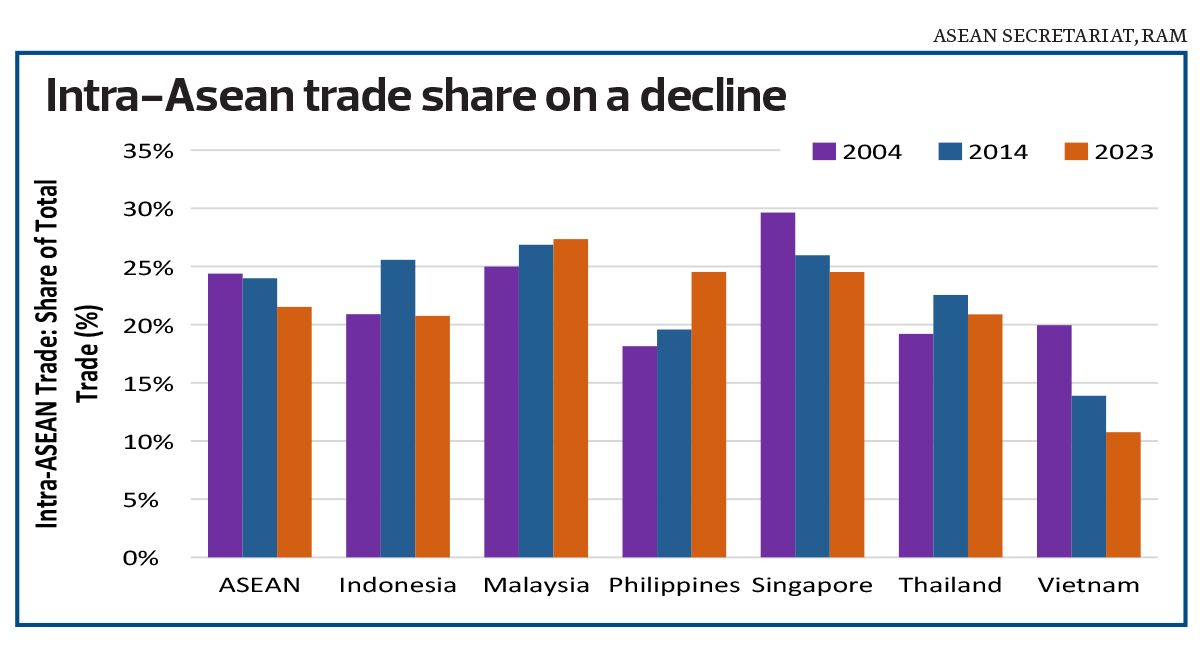

Moreover, the region’s share of intra-Asean trade has been on a declining trend despite the vast economic development the region has undergone. The intra-Asean trade share peaked at 25.1% in 2010 (up from 24.9% in 2005) but fell to 23.6% in 2015 and 21.2% in 2020.

The lack of progress in intra-Asean trade integration seemed rather broad-based as well. Among the Asean-6 — the largest economies in the bloc comprising Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam — only M alaysia and the Philippines have experienced an expansion in intra-Asean trade. In 2023, intra-Asean trade accounted for 27.4% of Malaysia’s total trade and 24.5% for the Philippines, up from 26.9% and 19.6% respectively in 2014. The other four nations continue to see a steady decline.

To boost regional trade, one of the steps Asean could take is to address persistent non-tariff barriers (NTBs) such as inconsistent regulations, cumbersome customs procedures and divergent technical standards. Overcoming these hurdles could encourage more Asean members to tap the broader Asean market and unlock further economic growth and, in turn, help to offset the decline in demand as major economies like the US turn inward.

That said, it is important to recognise that Asean’s economic size and purchasing power are still far from those of major economies like the US or European Union (EU). While Asean’s nominal GDP is slightly larger than India’s (US$3.6 trillion), it is far smaller compared with the US economy, which is at US$27.7 trillion. Even though Asean is projected to become the fourth-largest global economy by 2050, its current scale limits its ability to fully compensate for a major fall-off in demand from the US, which accounts for 26% of global GDP in nominal terms and remains the world’s largest consumer market. Additionally, Asean’s middle class, though growing rapidly, still has disposable income levels far below those in advanced economies.

Additionally, while deeper regional integration offers many benefits, it also carries risks of overexposure to regional shocks. History shows that overreliance on intra-regional trade can lead to vulnerabilities — as evidenced by the EU during the eurozone debt crisis as well as the disruption from the Russia-Ukraine war. Therefore, Asean must balance the benefits of integration with the need to diversify its trade partnerships beyond traditional markets like the US and China and mitigate the risk of being overly reliant on any single economy or region.

What’s next for Malaysia and Asean as a whole?

Asean is a dynamic and rapidly growing economic bloc with untapped trade potential, although its internal market remains modest. For Malaysia, its policy roadmap should therefore embrace a dual strategy. On one hand, enhancing regional integration can yield cost efficiencies, improve regulatory coherence and strengthen supply chain connectivity. On the other, Malaysia must also look beyond that and continue to pursue global market opportunities to fill any demand gaps that Asean’s smaller market cannot fully cover. Malaysia can build a robust economic ecosystem that leverages regional strengths while engaging global markets to ensure sustainable growth and stability in an era of ongoing global uncertainty.

Woon Khai Jhek, CFA is a senior economist and head of the economic research department at RAM Rating Services Bhd

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- HI Mobility debuts on Main Market with slight premium

- Iran oil-filled tankers build up off Malaysia as US sanctions mount

- Genting says Nevada authorities have signed off settlement terms for Las Vegas complaint

- Strong earthquake strikes central Myanmar, panic in Bangkok

- Tesla’s US$14b rally eclipses rout in other auto stocks

- Businessman who assaulted bodyguards for fasting sentenced to six years and 10 months' jail

- LSH Capital says former KL Tower operator’s lawsuit ‘without merit’, followed procurement process

- Strong earthquake strikes central Myanmar, panic in Bangkok

- Energy Commission introduces CREAM guidelines, expanding green energy options

- Israel vows forceful response after projectiles fired from Lebanon