This article first appeared in Forum, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 17, 2025 - March 23, 2025

In 2009, for the first time in human history, the global urban population surpassed the rural population. Malaysia followed a similar trajectory at an accelerated pace. At independence in 1957, only 23.4% of Malaysians lived in urban areas. By 1990, Malaysia had become an urban-majority country and, today, nearly 79.7% of its population resides in cities.

Urbanisation generally improves living standards. Cities create “agglomeration economies” — a concentration of industries, services and labour that generates cost efficiencies for both producers and consumers. Cities foster economic activity, creating cost efficiencies and facilitating access to healthcare, education and infrastructure.

Urban dwellers typically enjoy higher incomes and better services than their rural counterparts. However, unlike rural households, which can engage in subsistence farming, urban residents are entirely dependent on markets for food. This structural shift means food security in cities is determined primarily by affordability rather than availability.

When low prices don’t mean accessibility

Food prices are shaped by multiple factors, including agricultural production costs, transport expenses and government policies such as subsidies, tariffs and price controls. External pressures like energy price fluctuations, climate change and supply chain disruptions further contribute to food price volatility.

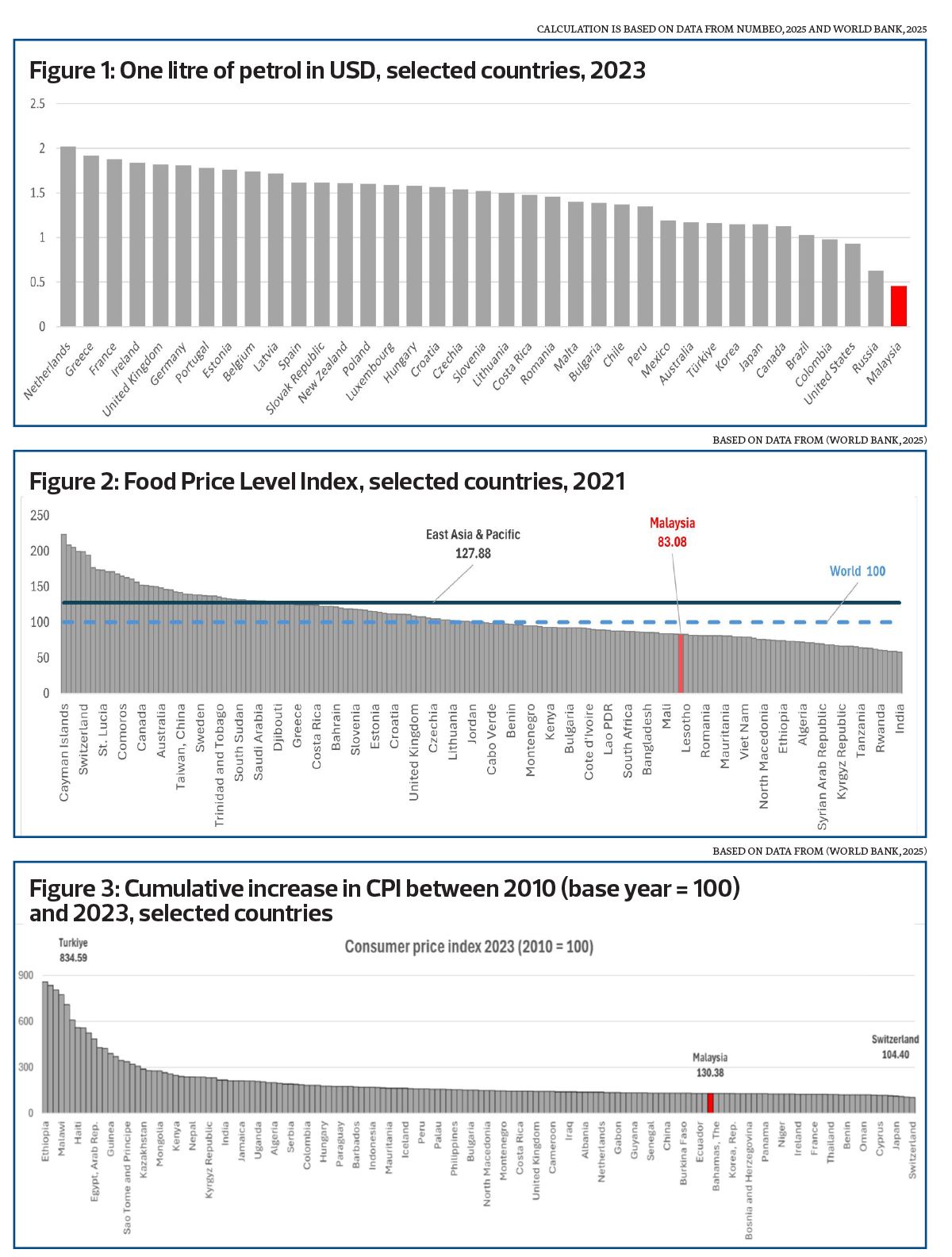

In Malaysia, government subsidies and trade policies play a crucial role in determining food prices. In 2022, Malaysia allocated RM55.96 billion (3.12% of gross domestic product) to subsidies, with over 80% directed at energy products, contributing to Malaysia’s relatively low fuel prices (Figure 1).

Malaysia’s combination of open trade policies and a broad subsidy system has established it as one of the more affordable countries globally. According to the World Bank’s Price Level Index (PLI), Malaysia’s food price level stands at 83.08% of the world average, making it one of the more affordable countries globally (Figure 2).

Furthermore, inflation has been moderate, with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increasing by 30% between 2010 and 2023 — lower than in many peer countries (Figure 3).

Despite these factors keeping food prices relatively low, affordability remains a challenge for many households, particularly low-wage earners who spend a significant portion of their income on food. The real issue lies in wage levels and income distribution rather than food prices alone.

The affordability gap

Despite lower-than-average food prices, many Malaysians still struggle to afford an adequate diet due to persistently low wages. Unlike rural populations who may have access to home-grown food, urban residents rely entirely on their earnings to purchase food. Compared with peer countries, Malaysia’s minimum wage is low.

In contrast to many other countries, where only a small percentage of workers earn at or near the minimum wage, in Malaysia, a substantial portion of the workforce falls into the low-wage category. The incidence of low wages — defined as earning less than two-thirds of the median wage — is particularly high in Malaysia, affecting over 30% of workers, more than double the 14% low-pay incidence rate observed in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

The affordability gap is further highlighted by differences in purchasing power. A minimum-wage worker in the Netherlands needs only four minutes of labour to buy one litre of milk, while a Malaysian worker requires 58 minutes for the same purchase. This disparity extends across essential food items, forcing many low-income households to substitute nutritious meals with cheaper, calorie-dense alternatives.

As income constraints limit food choices, households often opt for processed foods that are more affordable but less nutritious. The affordability gap is exacerbated during economic downturns, inflationary periods or unexpected financial shocks, further threatening food security for the most vulnerable populations.

The nutrition transition and its consequences

The high cost of nutritious food relative to wages limits access to a balanced diet, pushing low-income populations towards cheaper, calorie-dense alternatives. Urban residents, particularly low-wage earners, often rely on processed and fast foods, which are more affordable but contribute to rising rates of obesity, malnutrition and non-communicable diseases — a shift known as the “nutrition transition”.

In Malaysia, this trend is particularly evident among low-income urban households, where financial constraints restrict access to healthier food options. Inflationary periods, such as in 2022, further erode purchasing power, forcing many families to adjust their diets. A Unicef study found that 46% of surveyed families in 2023 reported increased consumption of instant noodles, up from 40% during the pandemic, reflecting a growing dependence on highly processed, low-cost meals as a coping mechanism.

As traditional diets rich in whole foods are replaced by industrialised food products,

diet-related health concerns such as cardiovascular diseases and metabolic disorders are on the rise. This is especially alarming in urban low-cost housing areas, where malnutrition takes a dual form. A 2018 Unicef Malaysia study found that 15% of children under five in low-cost flats in Kuala Lumpur are underweight, and 22% are stunted — both rates significantly higher than Kuala Lumpur’s average. At the same time, 23% of these children are overweight or obese, highlighting that urban poverty is not just linked to food insecurity but also to poor nutrition quality, reinforcing long-term health risks.

Policy recommendations: Bridging the affordability gap

Food affordability is not just about food prices; it is fundamentally linked to household income, wage policies and social protection mechanisms.

While a range of policy interventions — such as agricultural policies, price regulations and trade measures — can improve food affordability, below are three high-impact policy interventions designed to enhance the purchasing power of low-income households.

A. Establishing a social protection floor

A well-structured social protection floor is crucial for income security and food affordability, especially during vulnerable life stages such as childhood, old age, unemployment and disability. These periods heighten food insecurity risks due to income disruptions and increased nutritional needs. Aligning with International Labour Organization Recommendation No 202, a comprehensive system would ensure all Malaysians — regardless of employment status — can afford adequate and nutritious food.

Gaps in Malaysia’s social protection leave many, particularly informal workers, low-wage earners and the economically inactive, without sufficient financial security. Strengthening child benefits and income support for older persons and persons with disabilities would prevent food insecurity during economic hardship. A life-cycle approach can help reduce poverty and improve long-term health and development outcomes, especially for vulnerable children and elderly populations.

A detailed road map for financing and implementing this policy has been outlined in the study “Creating Fiscal Space for Constructing Malaysia’s Social Protection Floor” (SWRC & Unicef, 2024).

B. Expanding and strengthening the school feeding programme

A universal school feeding programme is a cost-effective intervention that addresses both food affordability and nutritional security for all children, especially those from low-income households. School meals ensure that students receive at least one nutritious meal per day, alleviating household food costs while improving cognitive development, school attendance and overall health outcomes. Research shows that school feeding programmes contribute to better concentration, reduced absenteeism and improved educational performance, particularly for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Although Malaysia has existing school feeding programmes, they remain limited in coverage and quality. Expanding access to all primary and secondary school students, particularly in low-income communities, would directly improve nutritional intake and economic security for vulnerable households. International evidence indicates that well-designed school feeding programmes have long-term socioeconomic benefits, including higher educational attainment, better employment outcomes and improved public health.

To maximise effectiveness, the nutritional quality of meals must be enhanced, ensuring that school meals provide adequate protein, micronutrients and balanced caloric intake rather than relying on cheap, processed foods. Strengthening meal composition and diversifying food sources within school feeding initiatives can further contribute to better dietary habits and long-term health improvements among school-aged children.

C. Automatic minimum wage adjustments

Malaysia’s minimum wage system lacks an automatic adjustment mechanism, causing wages to stagnate. Between 2020 and 2023, the minimum wage remained at RM1,200 despite rising living costs, eroding the purchasing power of low-wage workers. In response to public pressure, the government increased it to RM1,500 in 2023 and further raised it to RM1,700 in 2025. However, these adjustments remain sporadic and reactive, lacking a structured mechanism to ensure wages keep pace with the cost of living.

To maintain purchasing power, Malaysia should introduce an automatic wage adjustment mechanism, setting the minimum wage at two-thirds of the median wage. International evidence supports automatic adjustments — France indexes wages to inflation and blue-collar wage growth, the Netherlands adjusts wages biannually based on predicted increases and Poland raises wages when they fall below 50% of the average.

By adopting a structured wage adjustment system, Malaysia can prevent real wage erosion, ensuring households maintain access to essential goods, including nutritious food. Strengthening wage-setting mechanisms would also help reduce income disparities and align Malaysia’s labour policies with international best practices.

Dr Amjad Rabi is a visiting expert and Prof Datuk Norma Mansor is the director of the University of Malaya’s Social Wellbeing Research Centre (SWRC)

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Trump releases JFK assassination documents

- Siemens to cut 8% of jobs at struggling factory automation business

- Malaysian shares dip as investors return from holiday with caution

- Bangkok Airways seeks 30 new jets as TV series White Lotus boosts tourism

- US stocks hit by tech rout on eve of Federal Reserve decision day

- Canada ramping up efforts to expand trade and investment, including with Malaysia, says envoy

- Salim Fateh Din appointed MACC Anti-Corruption Advisory Board chairman

- BOJ keeps interest rates steady as Trump risks loom

- Contracts delays could snag on HE Group’s earnings, Phillip Capital slashes target price by 48%

- Trump releases JFK assassination documents