This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 17, 2025 - March 23, 2025

Financial institutions, especially fund managers and banks, were one of the first movers of the environmental, social and governance (ESG) movement in the private sector. As the purveyor of funds, these institutions began imposing ESG requirements on businesses that wanted financing or investments.

Recent global developments, however, seem to signal an end to this trend, as some call the “death of ESG”. Consequently, without the top-down directive from financiers and investors, there could be less pressure and urgency for businesses to adopt ESG.

The factors that are disrupting the growth of ESG investing are known by now. The new US President Donald Trump is against ESG and does not believe in climate change, and this stance has pushed companies to retreat from their commitments or soften their stance on these issues.

BlackRock, once a vocal proponent of ESG, has since dropped the term, and left the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative in January. So far, six major US banks have pulled out of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, which was followed by several large Canadian banks.

However, some industry players remain optimistic on the trajectory of ESG adoption and see this as a transition period, claiming that fund managers are now using ESG factors as a screen for potential risks and opportunities. This can be done not just for “ESG” funds but as part of the normal investment decision-making process.

“ESG investing is not dying; rather, it is undergoing a period of recalibration and evolution. While ESG fund flows have slowed globally, this does not indicate the demise of sustainable investing. Instead, the industry is likely experiencing a necessary reset, driven by shifting market dynamics, regulatory developments and evolving investor priorities,” says Hortense Bioy, global head of sustainable investing research at Morningstar, a US-based financial services firm that provides investment research and management services.

“Despite short-term headwinds, including general underperformance, greenwashing concerns, regulatory uncertainty and an anti-ESG sentiment, all types of investors, including large pension funds, continue to allocate capital towards sustainable investments.”

This was echoed by Elodie Laugel, chief responsible investment officer at Amundi, a large European fund manager with a presence in Malaysia. The subdued growth in sustainable funds last year, she says, was considered “market normalisation” from a rapid growth phase into a more stable and sustainable one.

“The industry is undergoing a necessary reflection on how to enhance transparency, accountability and alignment with sustainability goals. This reflection is crucial to address the environmental and social challenges of today’s economy while meeting the highest client standards,” says Laugel.

Big fund managers have influence over the local market by imposing their requirements — such as the need to have an independent board, a net zero or transition plan — on their portfolio companies, and by voting according to their ESG principles at annual general meetings of public-listed companies.

For instance, according to Amundi’s 2024 Voting Report, it voted against the climate transition plan and 2023 progress report of an oil and gas company in Australia. The fund manager asked the company to include Scope 3 emissions in its net zero ambitions, limit the use of carbon offsets and consider more profitable options to develop low-carbon solutions.

In another case, Amundi communicated its decision to require large companies in Japan to have at least two female directors, and opposed the re-election of representative directors in an IT company for failing to meet this requirement.

In Malaysia, Permodalan Nasional Bhd (PNB) updated its proxy voting guidelines to incorporate ESG-related considerations, and expects its investee companies to articulate their commitment to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 or sooner.

Ultimately, for fund managers, being able to deliver financial returns to clients in the long run is still their main responsibility. It could be said that these fund managers who integrate ESG into their decision-making, and continue to do so, may believe that ESG factors — such as climate change and diversity — have financial implications.

“Asset managers will do what’s best for their clients, regardless of who’s in the administration or what happens in industry groups. Some asset managers may believe that their clients will be best served in the long term by ignoring sustainability in investment decisions, and there will be some who believe that sustainable investing is the best way to serve their clients in the long term,” says Ou Yong Xuan Sheng, ESG analyst at BNP Paribas Asset Management, a prominent fund house from France that has a presence in Malaysia.

“We at BNPP AM still believe and are committed to the belief that sustainable investing is the better approach, and that’s why we have incorporated our Global Sustainability Strategy into 90% of our open-ended fund assets under management (AUM).”

What’s clear, however, is that the ESG fund market will continue to change due to new regulations to counter greenwashing, particularly from Europe, which has strict regulations on what can be called a sustainable fund.

Meanwhile, amid the changing geopolitical and economic landscape, companies may scale back their sustainability goals, and governments review their priorities.

All these would likely be done without much fanfare, in contrast with the overwhelming “green” publicity that companies have indulged in previously.

“We anticipate more ‘greenhushing’. More companies will avoid explicit ESG branding to sidestep political backlash, while still pursuing sustainable business practices,” says Morningstar’s Bioy.

There will be a “two-speed” world, she adds, whereby asset owners seeking strong ESG commitments may increasingly prefer European firms over their US counterparts, who may tailor their messaging to different audiences while avoiding public commitments.

“In Europe, sustainability continues to be a competitive advantage, while in the US, ESG investing becomes more politically and legally fraught,” says Bioy.

Declining interest from investors?

A peek at the data on how much investors are putting into global sustainable funds could offer a clearer picture of where things are going.

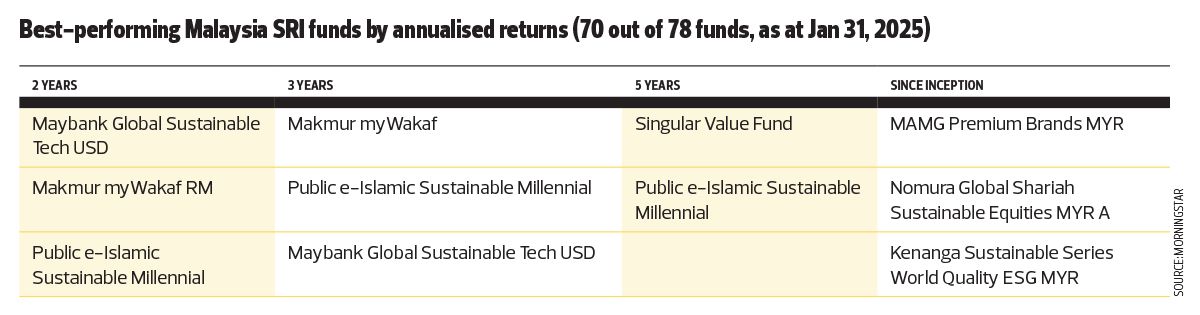

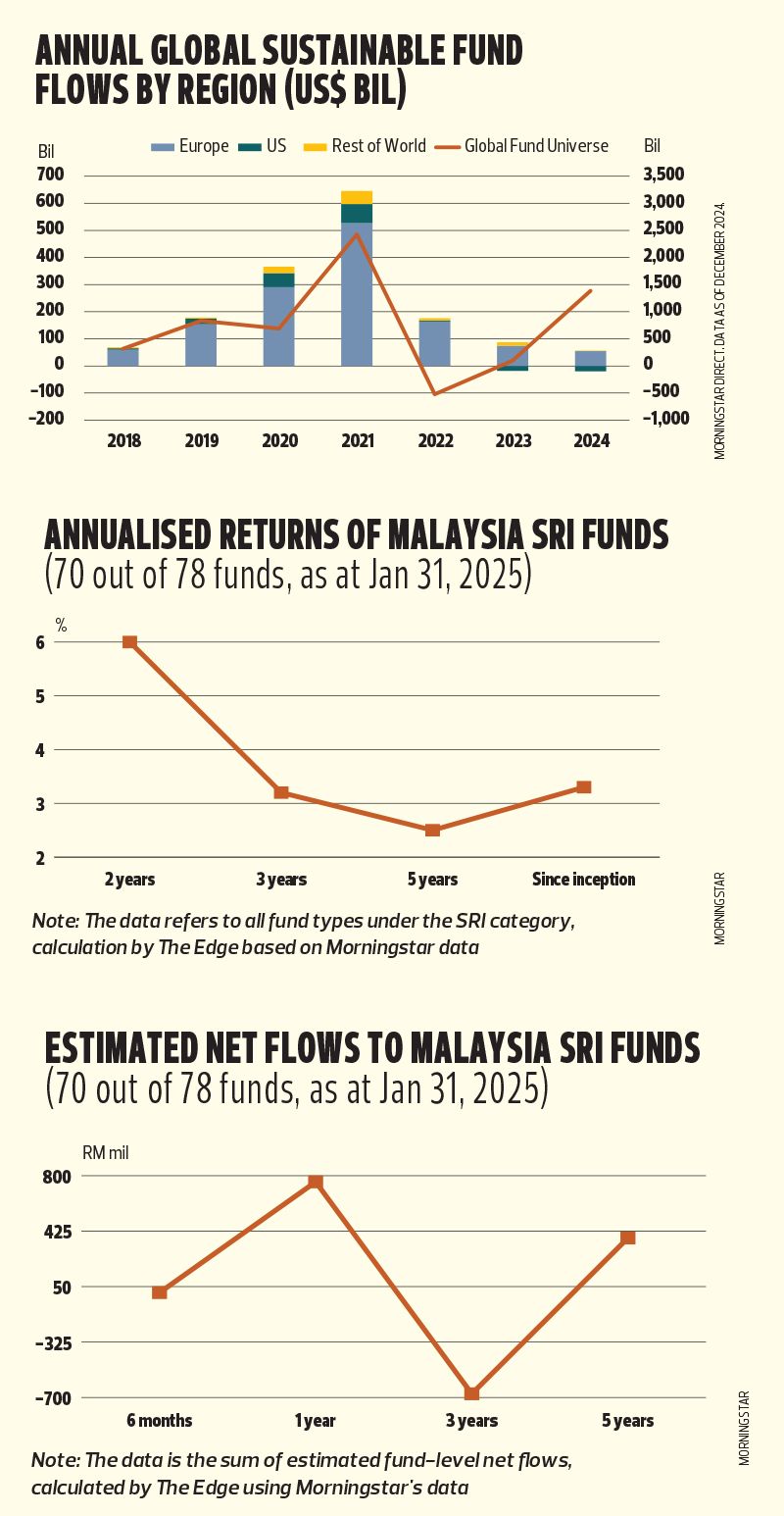

Inflows into these funds were at their peak in 2021, when the broader market also enjoyed record inflows, according to the most recent Morningstar’s Global Sustainable Fund Flows report. This fell by 75% in 2022 but remained positive, in contrast with the rest of the market that registered outflows.

In 2023, the demand for sustainable funds recovered, except in the US, where the exodus continued. However, inflows into these funds shrank by half in 2024, as the rest of the market enjoyed a boom. New sustainable fund launches have cooled down dramatically since 2022, and this is partially due to regulations to counter greenwashing in Europe, leading fund managers to be more cautious.

For context, the European Securities and Markets Authorities’ latest guidelines categorise funds into six buckets: transition, environmental, social, governance, impact and sustainability. Fund managers that want to use terms related to transition, social and governance in the fund name, for instance, must have 80% of its assets invested according to the environmental or social characteristic or sustainable investment objectives.

In Malaysia, the 70 Sustainable and Responsible Investment (SRI) funds (out of 78, as at December 2024), registered by the Securities Commission Malaysia (SC), have experienced net outflows in the past three years (based on the sum of estimated fund-level net flows, as at Jan 31, 2025), according to available data from Morningstar.

However, net flows were positive in the past one-year and five-year periods. Most SRI funds were launched in the past three years.

According to the SC, SRI funds must adopt one or more sustainability considerations, such as that of the United Nations Global Compact principles, the Sustainable Development Goals or any other ESG factors.

The funds must also adopt one or more of these strategies: ESG integration, ethical and faith-based investing, impact investing, negative screening (exclusion of sectors or companies with poor ESG performance), positive screening (prioritising certain sectors or companies with positive ESG performance), thematic investments and any other strategies authorised by the SC. The SRI fund must have a minimum asset allocation of at least two-thirds of its net asset value in accordance with these policies and strategies.

The major institutional investors in Malaysia — the Employees Provident Fund, PNB, Khazanah Nasional Bhd and the Retirement Fund Inc (KWAP) — have sustainable or ESG investing policies published online, with varying levels of details.

The private fund managers have pages on their website describing how they integrate ESG factors into their investment decision-making, with some being more explicit than others in explaining how they incorporate this screen for all their investments, and not just in the SRI funds.

Public Mutual, for instance, has seven SRI funds with an AUM of RM2.115 billion as at Dec 31, 2024. Its first SRI fund was the Public e-Islamic Sustainable Millennial Fund (PeISMF), which invests in component shariah-compliant stocks of ESG indices. PeISMF was among the top five funds with the highest annualised returns in the last two, three and five years, according to data from Morningstar (refer to table).

Chiang Kang Pey, CEO of Public Mutual, adds that the fund has also outperformed its benchmark since inception. The firm does see increasing interest in SRI funds. Last year, it launched another two SRI funds which generated a total AUM of RM727 million.

“The increasing AUM and sales of SRI funds indicate that there is positive interest from investors who have ESG considerations in their investment preferences,” says Chiang.

Sacrificing profits for ESG?

ESG-related matters, such as climate change, gender diversity, carbon emissions, labour rights and independent boards, are often pitched to financial institutions as factors that could negatively impact financial bottom lines if they are not managed well.

Therefore, investors would likely expect ESG funds to outperform conventional funds.

Luckily for them, the performance of sustainable funds, so far, is slightly more positive than that of conventional funds, according to various sources. But this depends on many factors.

According to Morgan Stanley’s Institute for Sustainable Investing, sustainable funds modestly outperformed traditional peers during the first half of 2024 due to their exposure to large-cap equities, since equity funds make up a larger proportion of the sustainable fund universe.

In the past five years, sustainable funds have delivered superior median returns of 4.7% in eight of 10 of the past half-year intervals. Sustainable equity funds also experienced lower volatility than conventional funds over that period.

On the other hand, Morningstar’s data of the 70 Malaysia SRI funds shows increasing positive annualised returns for the past two, three and five years (see graph).

The performance of ESG funds depends heavily on the fund manager’s strategy, and interestingly, on how the “Magnificent Seven” stocks — Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Meta and Tesla — perform.

The London Stock Exchange Group’s (LSEG) Sustainable Investment (SI) Insights report from January revealed that climate-focused equity indices outperformed while ESG-focused indices, such as the FTSE4Good, underperformed in the fourth quarter of 2024. The main reason for this disparity is the over or underweight positions in Tesla, which rose 54% in that period.

“SI indices continue to typically be overweight in the tech sector due to their normally strong ESG scores and relatively low-carbon intensity, although this is changing with growing power demand from artificial intelligence (AI) applications and data centres, and in some cases, involvement in green revenue activities,” says Lee Clements, head of applied SI Research at FTSE Russell, which is a subsidiary of LSEG. “However, with performance in tech being quite concentrated, there is an important selection effect as different SI strategies select between different tech companies, based on different criteria, such as ESG scores, carbon intensity or green revenues.”

This exposure to tech counters dragged the performance of ESG funds in 2022, when it was the worst-performing sector, while oil and gas (O&G), a sector that ESG funds tend to underweight or exclude, was the best performing, observes Bioy.

Now that Trump has promised to drill and export more fossil fuels, this could be a concern for ESG fund managers.

BNP’s Ou Yong, however, isn’t too fazed.

“I am personally not convinced that O&G production will increase at the president’s wish, given that there are many variables that have more influence over prices, such as Opec’s (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) production quota and China’s economic recovery. Further, given that the US domestically already produces more than it consumes, I don’t think the CEOs of US O&G companies will be incentivised to produce more, since that might put a downward pressure on prices.”

This might lead to higher prices for fossil fuels in the short term, but geopolitical risks are expected to have a more significant influence on oil prices, leading to a slight downward trend, observes Amundi’s Laugel.

“While this may create a more challenging environment for sustainable investing, we do not anticipate any disruption to screening and exclusion approaches in responsible investment. The growing recognition of climate risk as a material financial risk and associated costs for the economy, as well as the strong demand from investors for sustainable investment options will persist,” says Laugel. “Investors need to balance short-term market dynamics with long-term sustainability goals, recognising that fossil fuels may represent a short-term play while sustainable investments drive long-term value.”

According to Amundi’s research, some ESG indices outperformed by more than 600 basis points compared to the standard MSCI world indices, while other SRI indices heavily underperformed due to their respective exposure to the tech sector. However, Laugel observes that in the long term, there has been a slight outperformance of ESG indices when looking at the 10-year performance record.

On the other hand, not holding or underweighting O&G in 2023 and 2024, Bioy says, didn’t impact ESG fund performance as much in those years because energy stocks underperformed.

“Investments centred on ESG factors generally perform better during periods when less carbon-intensive sectors, such as technology and communication services, lead equity markets,” she says.

Many ESG fund managers use the best-in-class selection methodology, which means they only include the highest-rated stocks based on ESG risk within each sector.

“Since recent top-market performers have been concentrated in just a few sectors, this approach often results in missing out on certain high-return securities,” says Bioy, who cautions that investors shouldn’t expect ESG to thrive in every market environment.

“No investment strategy works all of the time … [However,] we have found that ESG screens have led to resilience in down markets, even in brutal downturns like in March 2020. Morningstar and Sustainalytics have documented links between ESG and factors like corporate quality and financial health. So, in the long term, there are reasons for investors to be encouraged about the prospects for ESG investments in their portfolios.”

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Pro-Trump senator meets China’s economy tsar amid trade tensions

- Bayer hit with US$2 bil Roundup verdict in US state of Georgia cancer case

- Japan, China, South Korea meet at geopolitical 'turning point in history'

- Trump pulls security clearances for Kamala Harris, Hillary Clinton

- Thailand drafts law to speed up US$29 bil transport link