(Photo by Shahrill Basri/The Edge)

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 10, 2025 - March 16, 2025

CEOs in Malaysia see a lack of availability of skilled workers as being the biggest threat to their business in the year ahead, a PwC survey shows. The result raises questions as to how this might impact companies’ growth plans and hiring.

Interestingly, this particular concern about skilled workers outweighed issues such as macroeconomic volatility and inflation, which appeared to be more pressing for their counterparts globally and in Asia-Pacific.

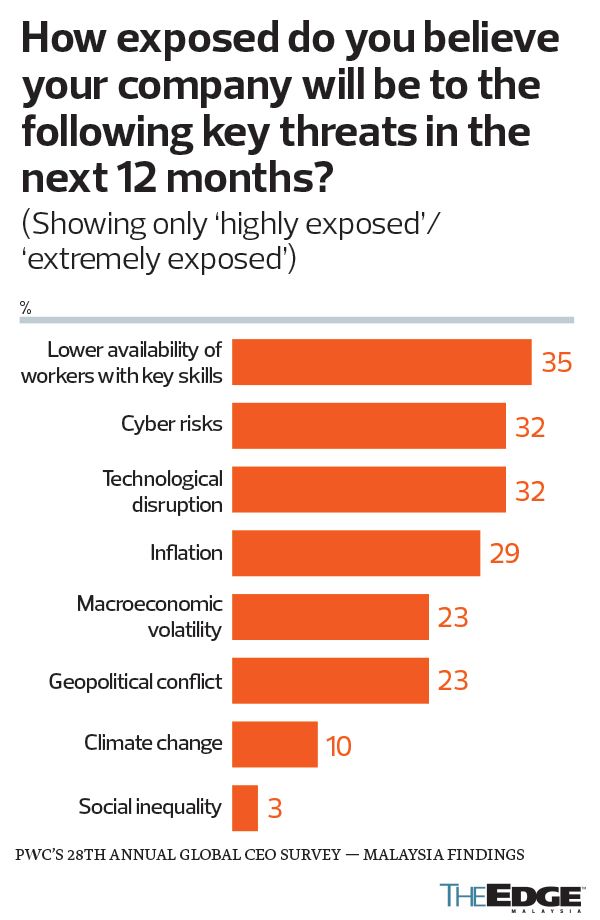

In the consulting firm’s 28th annual global CEO survey, conducted in October and early November last year, 35% of Malaysian CEOs cited “a lower availability of workers with key skills” as their top concern. Following closely behind were concerns over digital-related threats such as cyber risks and technological disruption (both 32%).

Only further down were concerns about inflation (29%) and macroeconomic volatility (23%). In contrast, global and Asia-Pacific CEOs cited macroeconomic volatility and inflation as their top concerns. The survey gathered insights from 4,701 CEOs, including 1,520 from Asia-Pacific and 31 from Malaysia.

That Malaysian leaders ranked a lower availability of skilled workers as their top concern is hardly surprising, says PwC Malaysia managing partner Soo Hoo Khoon Yean. “Many companies here face this problem, including us,” he says candidly. Brain drain is one reason for this, with Malaysia losing talent to Singapore, in particular.

“Malaysians are always in demand, generally, because of their proficiency in English. And given our proximity to Singapore and the relatively more attractive salaries in our neighbouring country, there is a natural tendency for people to move out [of Malaysia],” he explains.

But brain drain aside, there is also the issue of there being a widening of the skills gap. This refers to the mismatch between the skills that an employer expects and the actual skills employees have.

Skills that were acquired in the past may no longer be relevant today because of technology disruption, Soo Hoo notes. “The demand for certain types of skills is evolving, so people may not necessarily be equipped with the skills that are demanded by the business community.”

He believes that institutions of higher learning are not adequately addressing this issue. “I have shared with academics and varsities before: There is a gap between what has been taught in varsities and what business organisations require today. For example, people are trained [using] Excel spreadsheets. But today, [in business] we are talking about [using] data analytic tools. And recently, some data analytic tools are also obsolete because they don’t [incorporate artificial intelligence]. So, the skill sets that are required are different.”

While institutions of higher learning are trying to address the issue, the reality is that there needs to be better collaboration between the academic world and business industries, Soo Hoo opines. “Businesses must be able to work hand in hand with institutions of higher learning to make the curriculum more relevant.”

Asked if he saw a situation down the road where more organisations would have to undertake layoffs as they seek to rightsize their workforce and hire employees with the needed set of skills, Soo Hoo says: “I’m actually optimistic that there is no need for layoffs if you can reskill your staff. Train them in the skills you require.”

Increasingly, organisations are “re-looking” at a workforce of the future and at what skill sets are required. “It’s not about reducing 3,000 to 4,000 staff. It’s about how they can potentially move, say, 1,000 people out of areas that are increasingly going to be replaced by digital, to do something else of higher value. It’s about repurposing skills.

“For example, they can upskill a secretary to do concierge-type work. The secretary can perhaps specialise in managing business travel for the firm’s employees, as opposed to being someone who is answerable to just one boss. Companies can make those types of changes. Identify the people whom you want to upskill.

“So, really, the onus is on the organisation to have the political will to look into the future and repurpose the resources.”

An organisation needs to put time, money and effort into helping its employees progress, he stresses. “There is an acute need to repurpose skills.”

That the Malaysian government has recently increased the minimum wage for employees is positive, says Soo Hoo. But businesses should not be relying on the government alone to remedy the lack of availability of a skilled workforce. “The industry needs to come together and do its part,” he says.

While offering employees competitive salaries can help stem brain drain, what is often more important is creating the right environment and the right culture in the workplace for people to bloom, and investing in skill sets too, such that they will want to continue growing with the company, he continues.

According to a Malay Mail report last July, which cited Talent Corp Malaysia Bhd group CEO Thomas Mathew, about 1.86 million Malaysians had left the country in the past five decades. Extrapolated, this represented 5.6% of the population, significantly higher than the global average of around 3.6%, the report said at the time.

A Department of Statistics Malaysia study released in February last year on Malaysian citizens working in Singapore and Brunei in 2022 and 2023 showed that 39% of Malaysians in Singapore were primarily skilled workers while 35% were semi-skilled. In Brunei, 68% were skilled while 24.1% were semi-skilled.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Rich Chinese alleges family office staff in Singapore misused US$56m

- BofA survey shows biggest ever drop in exposure to US equities

- Indonesia’s Indrawati says she is not quitting as finance chief

- Bessent sees no reason for recession, economic data ‘healthy’

- Zulfikri Osman appointed Mara director general

- Siemens to cut 8% of jobs at struggling factory automation business

- Bessent sees no reason for recession, economic data ‘healthy’

- Tencent Music quarterly revenue climbs 8% on stronger streaming demand

- Alphabet to buy Wiz for US$32b in its biggest deal to boost cloud security

- Apple loses top court fight over German antitrust crackdown