(Photo by Patrick Goh/The Edge)

This article first appeared in City & Country, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 10, 2025 - March 16, 2025

With the towering city centre skyline, which includes the Petronas Twin Towers, as its backdrop, Kampung Baru stands as the last Malay enclave in the heart of Kuala Lumpur city centre. The 125-year-old settlement is home to century-old traditional Malay houses and families who have lived there for generations.

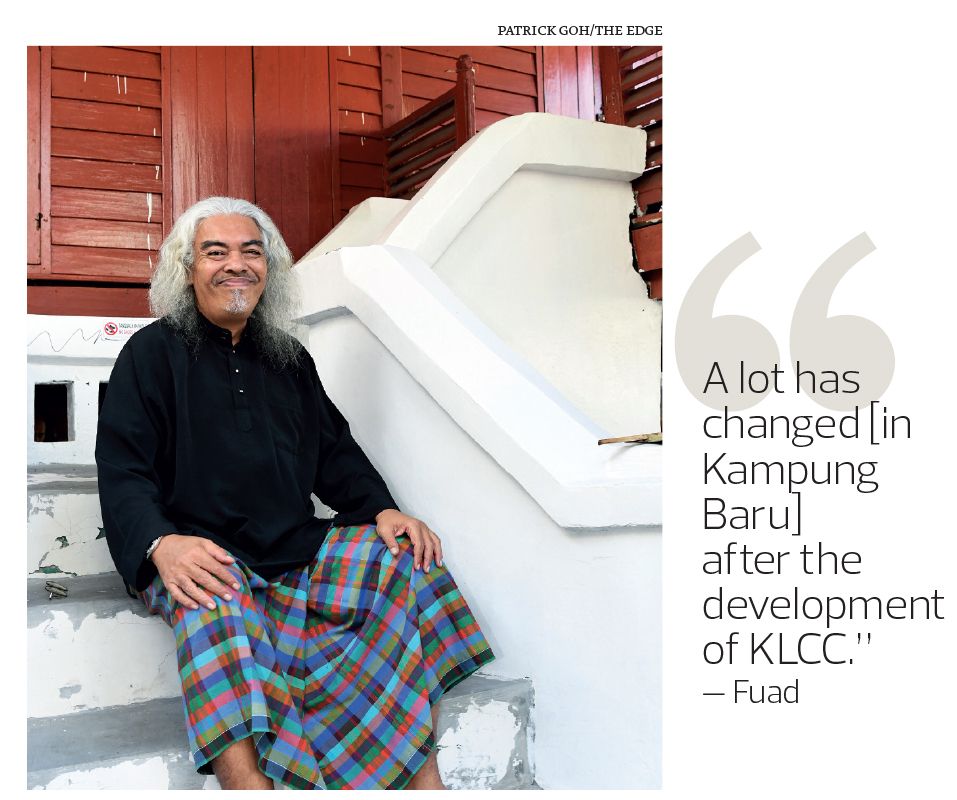

During a walking tour hosted by fourth-generation Kampung Baru native Fuad Fahmy Mubarak, City & Country briefly experiences the charms of the rustic Malay village, the warmth of its people and, of course, the food.

“[Kampung Baru] was gazetted by the Selangor government for the folks here to grow paddy. The idea was to use the waterway or Klang River [and Hale Road, now Jalan Raja Abdullah] to supply rice to Central Market and Ampang,” says Fuad.

“At the time, KL was booming because of tin mining, rubber and construction. So, the British segregated the Chinese who worked in mines to Chinatown, Indians who worked in estates to Brickfields and Malays [to grow] food. Kampung Baru used to comprise small pockets of settlements that were merged in 1900.”

The area he is referring to spans 225 acres and comprises seven smaller villages: Kampung Periok, Kampung Masjid, Kampung Atas A, Kampung Atas B, Kampung Hujung Pasir, Kampung Paya and Kampung Pindah, which consist of more than 800 plots collectively. This enclave has been recognised as a Malay Agricultural Settlement (MAS) since 1900. “[Kampung Baru] is the only one in the world with the MAS land status,” says Fuad.

Each of the seven villages has different demographics. “You’ll find many Javanese in Kampung Paya because they are good planters. My place is in Kampung Atas B. So, many of them, like me, are of Rawa descent, and there are Mendailing people there as well. Near the mosque are people from Melaka and Klang. These are some of the main sub-ethnic groups you can find in Kampung Baru.”

It is said that Kampung Baru was expanded to cover non-MAS areas, including Perumahan Sungai Baru, Kampung Padang, Kawasan Raja Bot and Pasar Minggu when the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur was established in 1974.

Including the non-MAS areas, Kampung Baru today spans more than 300 acres and is bounded by Jalan Raja Muda Abdul Aziz to the north, Jalan Tun Razak to the east, Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman to the west and Jalan Sultan Ismail/AKLEH (Ampang-Kuala Lumpur Elevated Highway) to the south, according to the Kampong Bharu Development Corp (PKB) website.

More than just an idyllic setting

To many, Kampung Baru may still seem like a village lost in time, but that is not so. “A lot has changed after the development of KLCC. There used to be an open drain in Kampung Baru where you could find small turtles and guppies. And being boys, we used to play kuda longkang with just pieces of wood and we’d race for 10 sen, 20 sen,” Fuad chuckles.

“When they were building KLCC, for five years non-stop [from 1994 to 1999], it was very noisy and you could hear sirens and people shouting using hailers. Before the Petronas Twin Towers, there weren’t many high-rise buildings.”

According to him, many Kampung Baru natives have moved out of the area and only about 40% have remained. “Like me, the third and fourth generations, after we got married, there was no more space. So, we had to leave. I’m now living in Sentul but my children go to school here. My office is also here.”

The remaining 60% of the population are foreigners, he adds. “That’s why you can see all these houses are rented by mostly foreigners. At last count, the population here was around 17,000.”

When we pass by a coin-operated laundromat, Fuad notes that these businesses do very well. “Many immigrants who live here tend to do two jobs and have no time to do laundry. Many of them work in hospitals as cleaners during the day and in restaurants until midnight.”

Locals typically operate stalls during the day or have small businesses, he says.

While much of Kampung Baru’s future hangs in limbo as redevelopment plans loom, life in the village goes on. We walk past a classroom of young children learning English, elderly residents taking a stroll as well as stalls selling food and sundry. It is common to see folks exchange greetings whenever they pass by each other.

It is also fascinating to see the myriad fruit trees flourishing in the enclave, including cempedak, tamarind, different types of mangoes, star fruit, jambu air, pomegranate, rambutan, lime and banana. Plants such as daun sirih, daun kaduk, bunga telang, chilli, curry leaves, kunyit and serai also grow in abundance in the backyards of homes.

“One of the reasons Kampung Baru was chosen was for its fertile land. Plant anything, and it grows. Folks here get their ingredients from their backyard. They don’t need to go to the shop,” says Fuad.

When it starts to drizzle, we take shelter under the roof of a traditional Malay house on stilts. “Houses like these are usually built without nails. We call it pasak dan tanggam (peg and mortise technique). And it has a very smart and simple design. The roof is designed to prevent rain water from gushing into the house. It also has a lot of high windows for ventilation. The kerawang (decorative carvings) is used to prevent glare and the flooring has gaps to cool the house naturally,” he says.

Apart from the added ventilation, the house is raised on stilts for storage, to be above flood waters and to deter intruders. “And usually, in houses like these, there are only two rooms — one for the parents and one for the girls. The boys will gelimpang, or sleep anywhere.”

Our next stop is a house at a junction with five intersections called “simpang lima”. “Here, you find kuih raya all year round,” says Fuad. A song plays in the background and an elderly woman comes up to greet us over the many types of kuih raya on display, including the honeycomb-shaped kuih loyang and kuih bahulu. “You come to Kampung Baru, there’s no fridge magnet or keychains, but we have our local delicacies,” he says as he pays for a tub of kuih bangkit.

There are also longhouses in the enclave. “One rumah panjang (long house) with five to six doors can give a rental income of about RM1,500 monthly. Let’s say the house can fit 10 people, so it’s around RM150 per head,” says Fuad.

While most properties in the enclave have gates or perimeter fencing, there are some areas that are completely gateless, reminiscent of typical kampung ones in rural areas. “This used to be how Kampung Baru was like 60, or even 50, years ago. That’s why until today, we are still a close-knit community.”

Tourism potential for authentic experiences

As the journey progresses uphill towards Kampung Atas B and A, the building architecture evolves from the traditional wooden homes to half-concrete, half-timber bungalows. We take a brief respite from the rain at a coffee kiosk outside one such property as we wait for our drinks to go before making our way to Fuad’s home, which is of a similar hybrid design.

“It’s a townhouse and originally had two rooms. My late grandpa used to live upstairs, and we live downstairs. This was built in the 1960s in line with the modernisation of Kampung Baru at that time, when the government gave a standard design and they helped you out with a loan. That’s why you can see some of these houses with a similar design in the area.” The house that his great-grandfather lived in is also located on the same street.

We get to experience Malay hospitality at Fuad’s home, a cosy and quaint space adorned with vintage collectibles, including the tepak sireh — a traditional Malay ceremonial betel nut container. “Just make yourself at home,” he calls out from the kitchen, from which he soon returns with a plate of murtabak and pisang goreng in each hand and sets them on the table, along with a pot-and-basin set.

“Basuh tangan first,” he says, lifting the pot from the basin and pouring water on our hands. “Not many people know about this. It’s just called tempat basuh tangan,” he laughs.

When his father comes in to say “hello”, it is easy to see where Fuad got his gentle and jovial nature. It is also not surprising to learn that he was inspired by his father, a former president of the Malaysian Association of Tour and Travel Agents (Matta) in the 1970s. His great-grandfather came to Kampung Baru in the early 1900s as a religious officer and became its first imam in 1907.

Fuad has been involved in the tourism industry since he graduated in 1992 and started his career as a travel agent. It was an unsuccessful out-of-state venture that led him to pursue the career as a walking tour host of his own backyard.

“When I came back with zero, I thought Uber looked nice. That was in 2015, 2016, before Grab. I asked a guest whom I picked up from the airport what he would like to do and he said he would like to do a city tour. That’s where I got the idea from. So, I made an itinerary and put it behind my seat. That’s how people started coming for my tours. I also got my friends [who are travel agents] overseas to include a three-hour Kampung Baru tour if they have a three- to four-day KL itinerary. It all started from there.”

Fuad’s walking tours of Kampung Baru and Chow Kit can be found on online platforms such as Airbnb, LokaLocal and Pelago by Singapore Airlines. He has also collaborated with The Chow Kit, An Ormond Hotel to offer walking/foodie neighbourhood experiences.

“Also part of it is because I grew up in Kampung Baru and Chow Kit. So, I have many interesting stories and off-the-beaten-track places to share,” he says.

Fuad believes Kampung Baru has more to offer in terms of authentic tourism, and one way to go about it is to convert abandoned houses into homestays or galleries.

“For homestays, some properties can easily reach an occupancy rate of 90% at RM200 a night. That’s a lot of money, but owners have yet to digest and buy into that idea. That’s my challenge here in Kampung Baru,” he says.

Such a move would benefit everybody in Kampung Baru, from local businesses to transport operators such as e-hailing and taxi drivers. “I can also share what I earn with the kampung people. So, it’s a nice thing to do. I’ve already forwarded these ideas to PKB, as it is now the authority here in terms of development. PKB and DBKL (Kuala Lumpur City Hall) are now looking into sustainable development. So, I think I fit in their plans well and they support me, in a way.”

Something interesting Fuad brings up is that the number of local visitors increased after the pandemic.

“Before Covid, 90% of my guests were foreigners. Now, around 30% are locals. You’d be surprised that most of them are Gen Zs and millennials. They prefer a more authentic kind of experience. It’s a good change,” he says.

“The only thing now is to get owners to convert their homes into a homestay. If that can be achieved, I think I’ve done what I can for Kampung Baru and I hope the next generation can continue from there.”

Fuad ensures we are well fed, bringing us to Din Satay for dinner, where we share an aromatic plate of satay with Teh O Panas as the perfect accompaniment while we continue to chat into the night.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- MN Holdings, Genting, MMAG, LSH Capital, Able Global, Kerjaya Prospek Property, Yinson, GUH Holdings, DNeX and Sarawak Cable

- Loke assures thorough probe into Kluang fatal crash

- China's top airlines post fifth year of losses in 2024 in the face of domestic competition

- Musk’s xAI start-up swallows up X social network in surprise deal

- Zelenskiy cautious about new minerals deal but says past US aid not a loan

- Malaysia to deploy Nadma teams to aid Myanmar's earthquake relief operations

- Stocks lose ground amid inflation, trade war worries; gold at record high

- OpenAI must complete for-profit transition by year end to raise full US$40b — Reuters

- Seeking opportunities in a risk-off market

- Zelenskiy cautious about new minerals deal but says past US aid not a loan