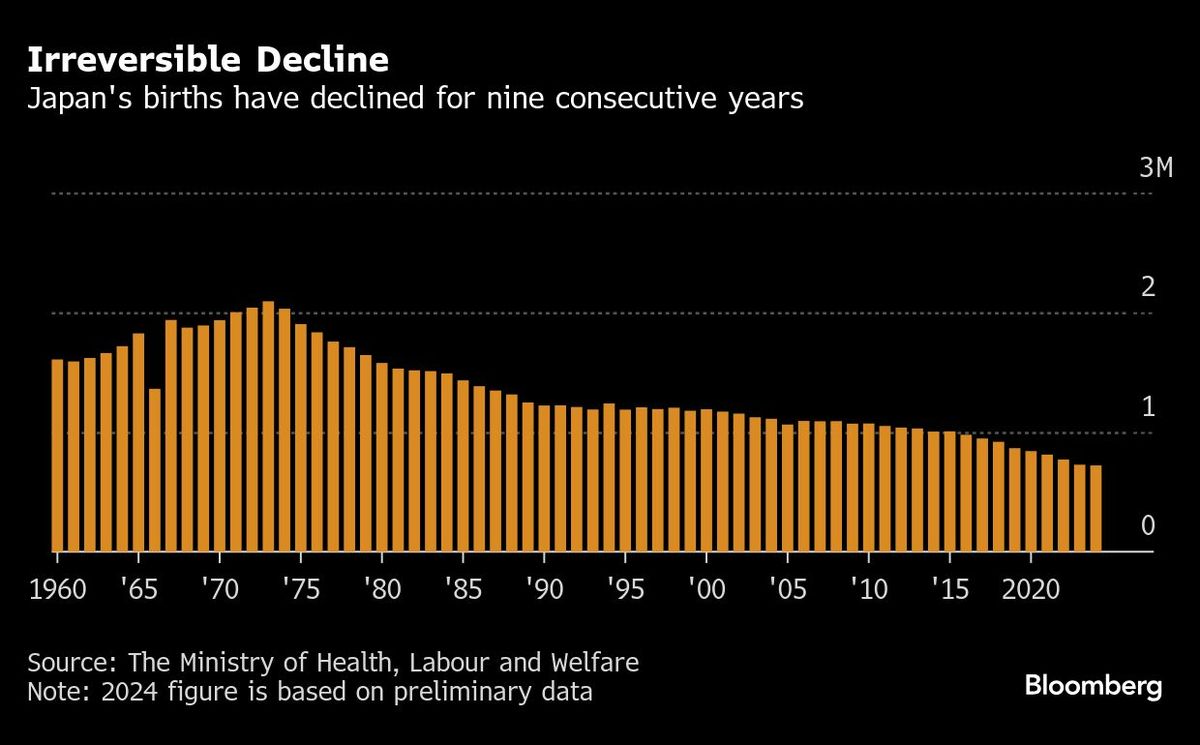

(Feb 27): The number of births in Japan fell to another record low, underscoring the growing challenge of how to shoulder ballooning social security costs for an ageing society with what’s already become an ever shrinking pool of tax-paying workers.

The number of newborns in 2024 fell 5% from the previous year to 720,988, extending a nine-year streak of declines, according to preliminary population data released Thursday by Japan’s health ministry. The reading marked the lowest tally since such records began in 1899.

Deaths rose 1.8% to a record-high 1.62 million for the same period, resulting in the biggest ever annual decline in total population, the report showed.

The sustained decline in the nation’s births adds to the urgency for a government already bearing the heaviest debt load among developed nations. Japan’s public debt will be 232.7% of gross domestic product this year, according to a report from the International Monetary Fund.

It’s also part of a widening global trend. South Korea’s fertility rate edged higher last year for the first time in nine years, but at 0.75 remains well below the rate needed to maintain the population. The drop in births in France accelerated in 2023 to the fastest pace in half a century, while China’s population has declined for three straight years.

Fewer workers means less tax revenue for government coffers while also pressuring businesses coping with staff shortages.

Since Japan’s working-age population peaked in 1995, its labour market has remained relatively tight. The unemployment rate is 2.4%, the lowest among OECD countries, and has stayed under 3% for almost four years. By 2040, Japan is projected to face a labour shortfall of 11 million, according to an estimate by Recruit Works Institute.

In 2024, a record 342 Japanese companies went bankrupt due to the labour crunch, according to a survey by Teikoku Databank data.

Meantime Japan’s social security costs continue to climb as a growing proportion of the population surpasses retirement age. For the fiscal year beginning in April, the government has allocated ¥37.7 trillion (US$253 billion or RM1.13 trillion) for social security, a nearly 20% increase over the past decade.

Japan’s pension system is also under pressure, with fewer contributors and more recipients. In the past two decades, the number of those paying into it has fallen by about three million, while the number of recipients has risen by nearly 40%, according to the welfare ministry.

The ongoing decline in births partly reflects younger generations’ reluctance to have children, despite recent government efforts. Building on his predecessor’s initiative, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is promoting a ¥3.6 trillion childcare policy package, which includes support for expectant parents and improvements to working conditions for childcare workers.

Despite the increasing outlays, births fell far short of the main scenario forecast for 2024 by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. The government-backed institute had projected 779,000 births for the year.

Uploaded by Chng Shear Lane

- Appellate court upholds quashing of proposed RM86.77 mil fine against Grab, two others

- Richest woman in Indonesia loses US$3.6b in just three days

- Affin Bank to distribute Bitcoin fund managed by Halogen Capital

- Malaysian shares dip as investors return from holiday with caution

- Private hospitals association reject calls for three-year costs freeze, regulation of pharmaceutical pricing

- Foxconn sees server revenue surpassing iPhone revenue in two years — report

- TSR bags RM219 mil earthworks contract in Kwasa Damansara

- Ex-PM Ismail Sabri quizzed by MACC for over six hours

- Global 195 legal coalition set up to pursue Israeli war crimes suspects for crimes against humanity in Gaza

- Close to 5,000 ESG funds in Europe now hold oil, gas and coal