This article first appeared in Digital Edge, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on February 10, 2025 - February 16, 2025

In the pursuit of becoming a digitally driven high-income nation, the Malaysian government has moved much of its administrative functions online. Services such as tax filings and permit applications are now just a few clicks away.

But this convenience comes at a cost. Safeguards have not always kept pace with the evolving technology, leaving some government websites alarmingly vulnerable to threats.

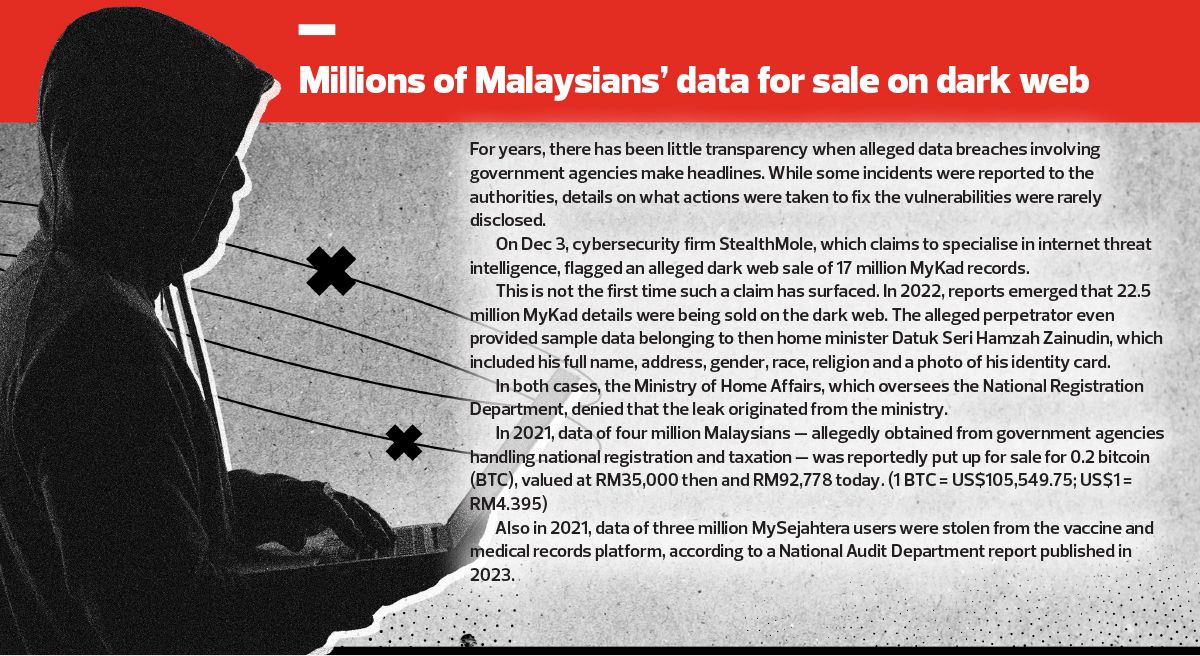

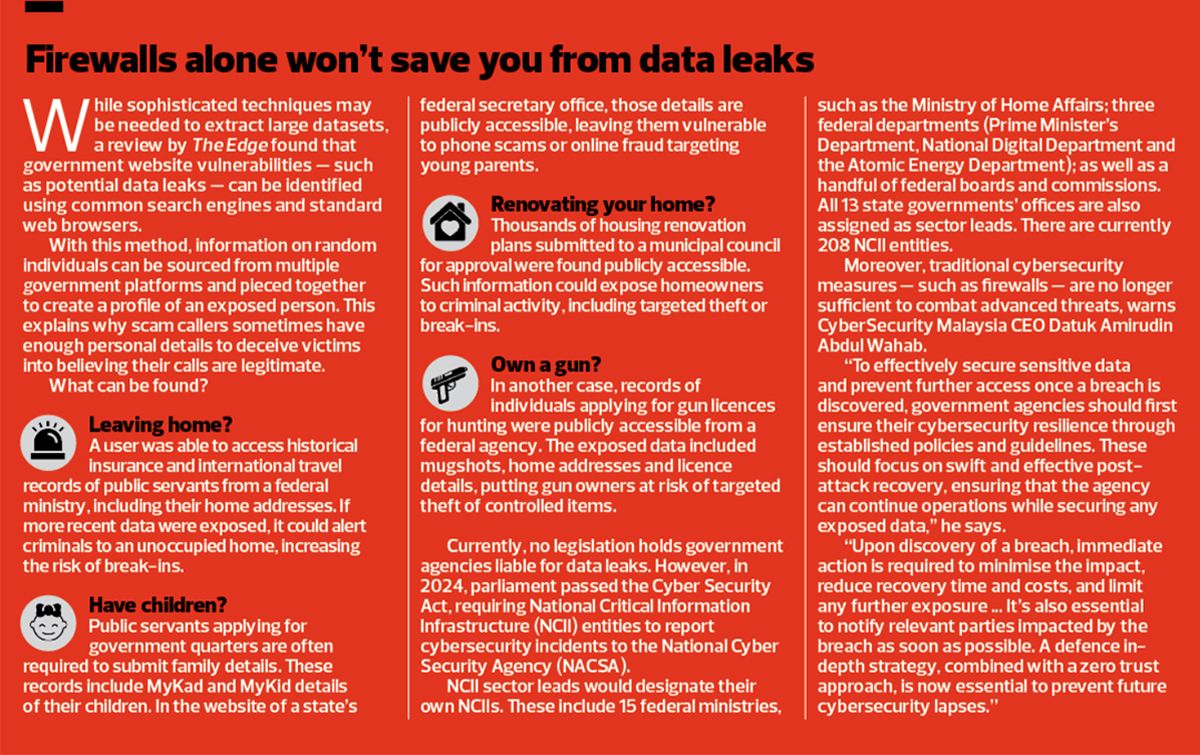

Personal data — including copies of identity cards, home addresses, financial records, household details, travel history and even gun ownership records — can sometimes be accessed without hacking, using nothing more than a web browser and a search engine (see “Firewalls won’t save you from data leaks”).

A review by Digital Edge found that municipal councils, government ministries and state-linked agencies have left sensitive data exposed on public servers, requiring no authentication to view. In some cases, a simple keyword search is enough to retrieve them.

This is because improperly secured websites, storage systems or repositories leave personal information accessible to anyone who knows where to look, says a source, an ethical white hacker.

For many government agencies, the danger is invisible. They remain unaware that their systems are leaking sensitive information — data that, in the wrong hands, can be exploited for scams, identity theft or other malicious purposes.

It is important to note that the issue does not merely lie with the sophistication of the cyberattacks, but in poor housekeeping practices as simple as requiring a password on a file, the source adds.

Recognising the problem, the goverment enacted the Cyber Security Act 2024 in August last year, in hopes that it will address existing gaps and strengthen the country’s cyber defences. Under the law, only qualified and licenced professionals are permitted to offer cybersecurity services to both government and private sector entities.

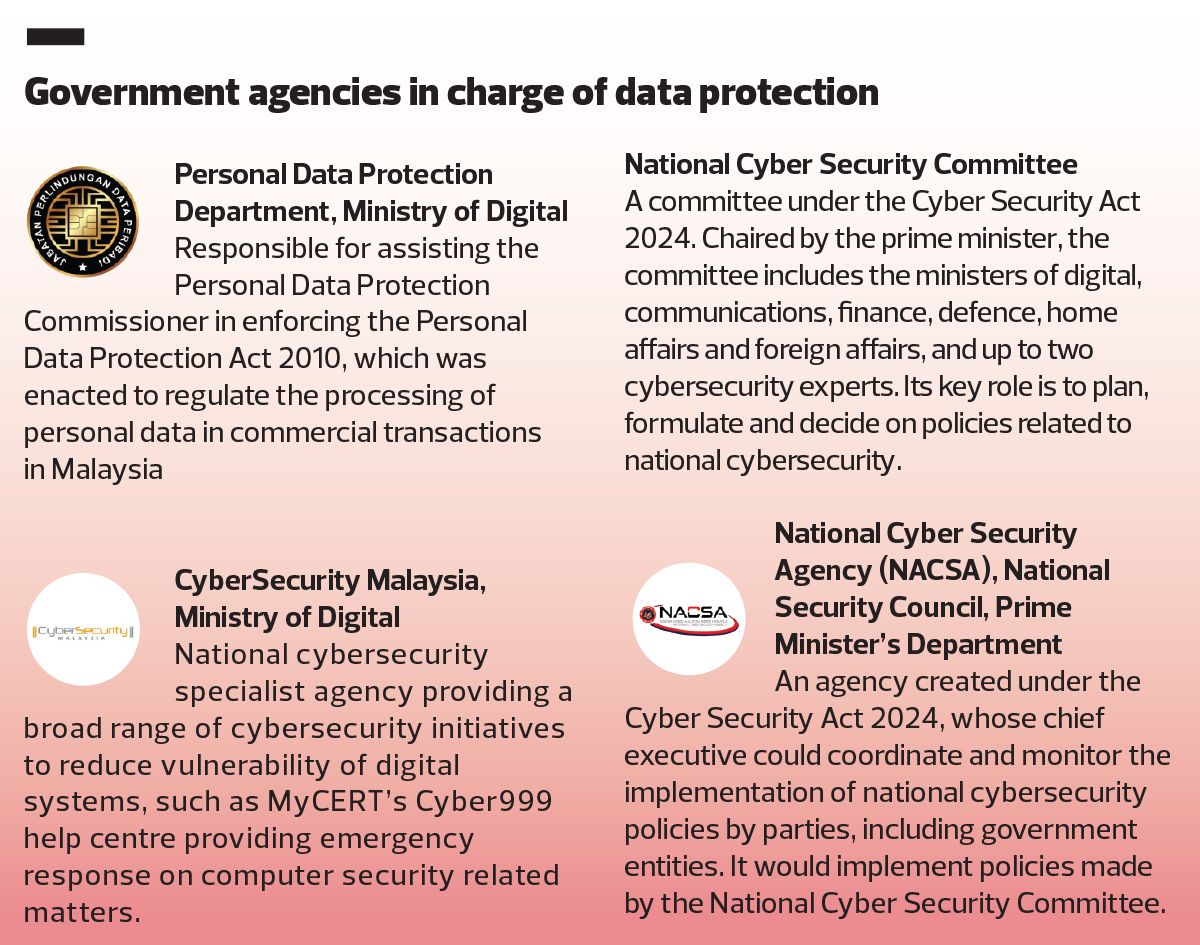

“This licensing mechanism allows for us to also monitor those providing cybersecurity services to government and non-government [entities],” says National Cyber Security Agency (NACSA) CEO Megat Zuhairy Megat Tajuddin in an interview with Digital Edge. Under the Cyber Security Act, NACSA is the federal agency responsible to coordinate and monitor the implementation of national cyber security policies by government entities.

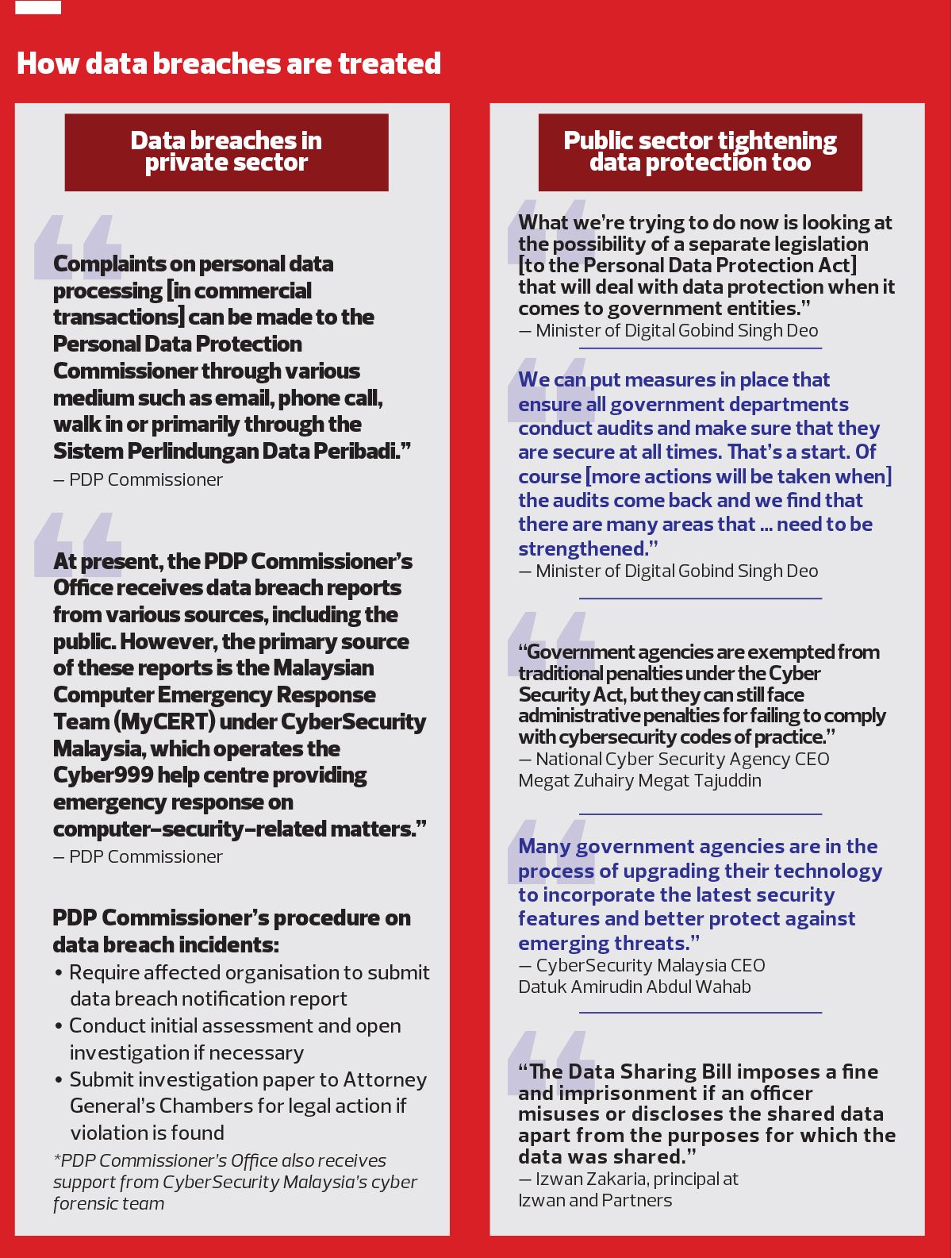

Before the Cyber Security Act was enacted, there were no provisions holding the public sector accountable for data breaches. The Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) 2010 primarily applies to data protection involving private commercial transactions and exempts the public sector.

Minister of Digital Gobind Singh Deo told Digital Edge in December that the government had considered expanding the PDPA to cover public sector agencies.

“That was one of the things that I was speaking about and tried to push for in the amendments that we tabled in July. But I did not get any agreement on that. What we are trying to do now is we’re looking at the possibility of a separate legislation,” he added.

“I think it’s important for us to ensure that we are able to assure everyone that their data is protected. Of course, one of the areas that they always talk about is what happens when it comes to the government.”

Following the enactment of the Cyber Security Act, Parliament passed the Data Sharing Bill in December.

The former designates NACSA as the lead body responsible for safeguarding national cybersecurity. As part of its mandate, NACSA has recommended “several measures to enhance data security within government agencies”.

Despite these measures, government agencies are exempt from criminal penalties such as imprisonment or fines under the Cyber Security Act.

Nevertheless, NACSA has other ways to hold them accountable. The Cyber Security Act legal framework compels government entities to adopt stricter cybersecurity standard, adds Megat Zuhairy.

“I do agree there are several agencies where you can easily Google and [obtain] information. But I think by having the Cyber Security Act and identifying National Critical Information Infrastructure (NCII), then [these agencies] are bound to protect themselves. One of these is to [adopt] all necessary cyber hygiene measures. Non-compliance is basically non-compliance to the law,” he says.

“Although Act 854 (Cyber Security Act) exempts federal and state governments from being penalised in terms of imprisonment or other penalties, we have other means to penalise responsible agencies for not fulfilling the requirement of them being NCII entities.”

Without mentioning the specifics, he adds that these penalties are imposed following a disciplinary inquiry.

Privacy Act is long overdue

Given that the Cyber Security Act exempts both the federal and state governments from prosecution in the event of non-compliance, Izwan Zakaria, principal at Izwan & Partners — a corporate law firm focusing on advising technology companies and startups — suggests that introducing a Privacy Act legislation could provide statutory recognition of individual privacy rights.

“The context of the Cyber Security Act is for the law to be legally binding, against the federal government and state governments, which must comply and abide by the [Act], unlike the PDPA, which only applies to commercial entities. Since the law is still new, we have yet to see the enforcement and effectiveness of the Act,” he says.

The rationale for exempting government agencies from the PDPA is that personal data collected by the government is typically used for administrative or regulatory purposes, not commercial gain, explains Izwan.

“Additionally, considering that the PDPA is a statute passed by Parliament, the law would likely need to be reviewed and replaced with a new supplemental bill to incorporate additional provisions catering to the public sector’s obligations,” he says.

Therefore, applying the PDPA to government entities would require significant modifications, particularly in terms of enforcement mechanisms and penalties.

A Privacy Act, on the other hand, could provide legal clarity and protection of personal privacy, define public sector obligations and establish remedies in case of breaches, he believes.

If a new law on government data protection is introduced, NACSA may be expected to coordinate with a newly established committee or oversight body under the legislation, says Izwan. This would help streamline the implementation of the data protection framework, particularly in terms of technical and cybersecurity measures.

“A dedicated law like a new Privacy Act would likely permit individuals to seek legal redress, including potential monetary compensation if they are able to prove that they suffered personal harm as a result of the data breaches. Additionally, government agencies may likely be expected to be strict and vigilant in their data handling practices,” he says.

While it may be a while for the Privacy Act.

Datuk Amirudin Abdul Wahab, CEO of CyberSecurity Malaysia, says that establishing a clear regulatory framework for data sharing within the government — aligned with global best practices — can help address existing legislative gaps. CyberSecurity Malaysia, tasked by the government, provides cybersecurity education, promotion and assistance to internet users in the country, serving as both a cyber emergency service and a security advisory for the public, businesses and government.

A step in this direction was taken with the passage of the Data Sharing Bill, which aims to facilitate data exchange between government agencies while imposing stricter safeguards.

The legislation includes a fine and imprisonment for misuse, holding government officers accountable if they improperly disclose shared data beyond its intended purpose. It also extends these obligations to third parties engaged by agencies for data-related work, requiring them to adhere to the same security and confidentiality standards.

Under the bill, the data provider needs to assess whether the requesting government agency has the necessary security and technical safeguards in place before any data can be shared with the agency.

Furthermore, government agencies are empowered to reject data-sharing requests under specific circumstances, including concerns about national security, the protection of confidential sources,

solicitor-client privilege or insufficient security measures on the part of the requesting agency, says Izwan.

“When we look at the Data Sharing Bill, it contains provisions to ensure that data is protected. That is in the sense of data being shared among government agencies. Moving ahead, we are looking at separate legislation to make sure that data handled by the government is secure,” Gobind says.

A National Data Sharing Committee consisting of various ministries will also be set up. This committee will formulate policies for data sharing and oversee the implementation of the bill. The committee will be answerable to the cabinet.

“Considering that the Data Sharing Bill was only passed in late December 2024, we may have to anticipate further subsidiary legislations to better understand how such data sharing will be implemented among public agencies. For instance, we may see more manuals, directives and guidelines from the National Data Sharing Committee that will apply to the affected agencies,” says Izwan.

Stepping up to safeguard data

Sensitive data can become publicly accessible due to a range of technical, procedural and human flaws, says Aaron Ikram Mokhtar, a cyber safety trainer and advocate at Digital Ihsan.

Common vulnerabilities include outdated security settings, weak authentication measures, improper data handling, insufficient encryption and failure to update software, he explains. Other risks stem from human errors, third-party vendors, lack of continuous monitoring and legacy systems that are incompatible with modern security protocols.

Without regular audits and enforcement of cybersecurity best practices, even small lapses can have significant consequences, he points out.

“Many things have to be done correctly to ensure data security. All it takes is one weakness or flaw and the system becomes vulnerable. Things like technical safeguards, access control, employee training, monitoring and auditing, vendor management and policy enforcement all have to be taken into consideration. For cybersecurity to be effective, it has to be planned into the system, it can’t be added haphazardly,” says Aaron.

“If budgets are not utilised correctly, the right people are not hired for the job and proper procedures and measures are not implemented correctly. [These vulnerabilities] will continue to be an issue. The government serves the people, and if taxpayers’ money isn’t being used correctly and there is proof of negligence, the people entrusted with our information should be held accountable.”

Considering most Malaysians take personal data protection for granted, these exposures leave them even more vulnerable to scams. Scammers can exploit details such as names, addresses and identification numbers to impersonate victims or manipulate their family members — often without them realising their information has been compromised.

“Whether it is financial institutions, healthcare providers or public sector bodies, sensitive information falling into the wrong hands can lead to issues like identity theft, fraud and reputational damage. For governments, these risks are amplified because they handle critical data tied to citizens and national security, but the underlying challenges are universal,” says Sarene Lee, country manager for Malaysia at Palo Alto Networks.

This is why it is pertinent that government agencies adopt a comprehensive, adaptive and dynamic approach to cybersecurity that integrates people, processes and technology to prevent future cybersecurity lapses, says Cybersecurity Malaysia’s Amirudin. He points out that a security operations centre is also critical for agencies to continuously monitor potential threats, respond in real time and manage incidents throughout their life cycle.

Regular monitoring and audit activities are key to ensuring that processes and standards are consistently followed in the government sector, says Amirudin, as these agencies have to handle a significant amount of public data.

“While achieving 100% security may not be possible, the key is to prepare for and minimise the impact of potential cyber attacks. It’s no longer just about preventing attacks but understanding how to quickly recover and resume operations if one occurs,” he says.

“In addition, having a well-defined data breach response plan is highly recommended. This can help minimise financial losses, avoid legal complications, reduce downtime and protect the organisation’s reputation. The faster and more effectively the breach is contained, the less the reputational damage, which ultimately helps preserve trust.”

Meanwhile, NACSA consistently monitors and encourages government agencies to conduct cybersecurity audits, penetration testing and risk assessments to identify potential weaknesses, says Megat Zuhairy.

He reiterates that public agencies need to adopt best practices in cybersecurity, such as encryption, multi-factor authentication and secure coding. Additionally, continuous monitoring and incident response frameworks should be in place to promptly identify and mitigate threats in real time.

“While cybersecurity is a shared responsibility, each government agency is ultimately accountable for protecting its own digital assets, as it best understands its infrastructure and needs. We strongly encourage cybersecurity practitioners, including the white-hat hackers, to report security flaws to us,” says NACSA’s Megat Zuhairy.

Palo Alto’s Lee stresses that adopting a zero trust framework is one of the most effective solutions against data leaks. This means that every user, device and request is continuously verified, making it incredibly difficult for unauthorised parties to breach security systems.

“By ensuring that no implicit trust exists, the zero trust framework minimises the likelihood of unauthorised access, even if certain credentials are compromised,” she notes.

Consistent monitoring of networks and all connected devices is essential to prevent data leaks, says Lee. This allows for real-time detection of vulnerabilities or unusual activity, enabling swift action to address potential threats before they escalate.

Lee recommends continuous vulnerability scanning, prioritising severity of vulnerabilities and exposures, centralised policy and monitoring as well as leveraging automation for prioritisation to effectively secure systems and prevent unauthorised access to sensitive data.

For the government, the Cyber Security Act is seeing measures put in place “to ensure all government departments conduct audits” and make sure that they are secure at all times, Gobind said in the interview in December.

“That’s a start. Of course [more actions will be taken when] the audits come back and if there are many areas that need to be strengthened. We are currently working on that now with NACSA and Cybersecurity Malaysia.

“That is something that I think will take some time … I think one can acknowledge that there is a problem, but steps are being taken to improve security as we go along. We hope that we will be able to see things improve.”

Critical data deserves stronger protection

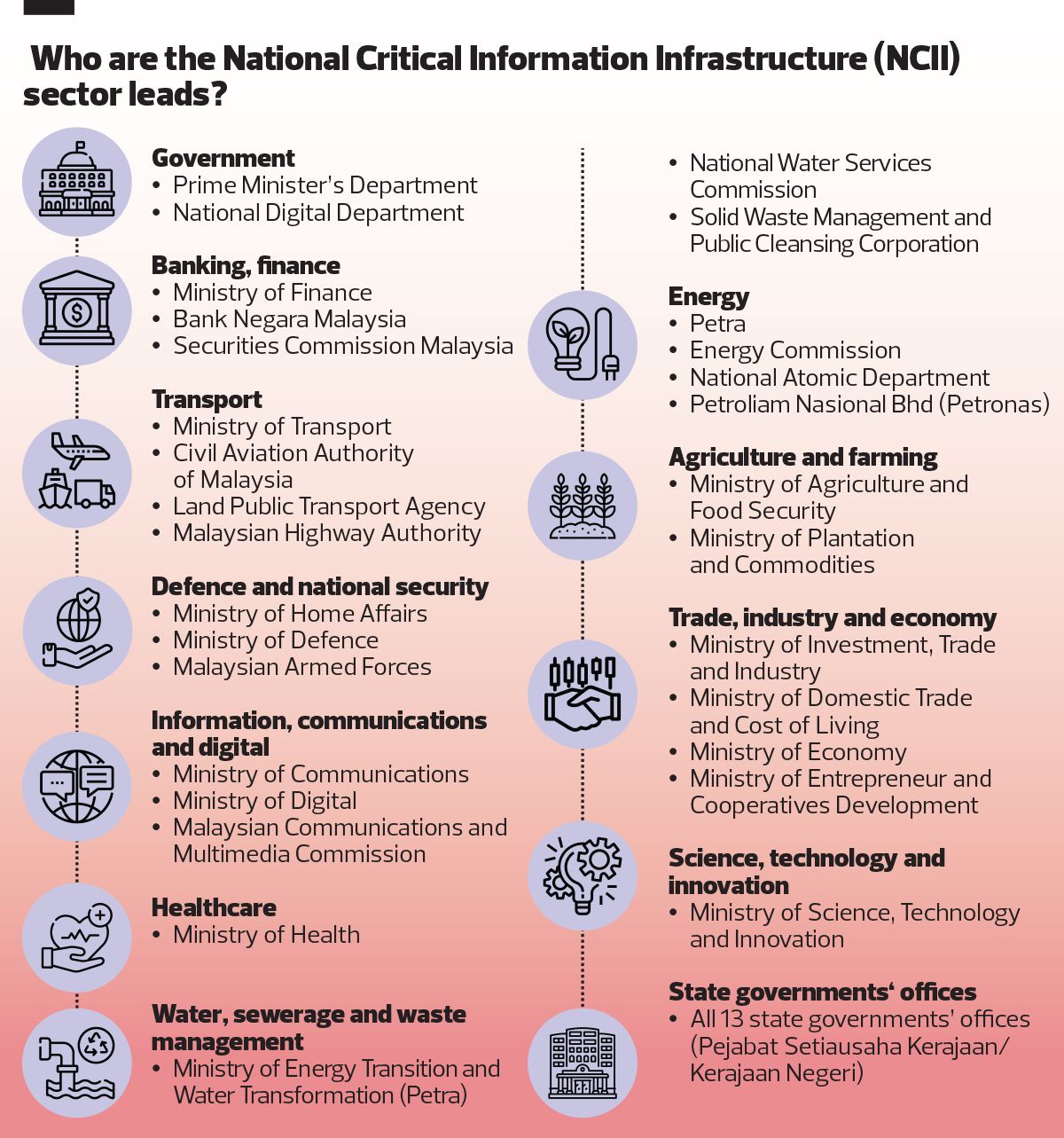

The Cyber Security Act mandates that entities designated as NCII report cybersecurity incidents to NACSA. NCII refers to essential systems comprising electronic information assets, networks, functions, processes, facilities and services within an information and communications technology environment.

These systems play a vital role in a nation’s stability, where any disruption or damage could impact national defence and security, economic stability, government operations, public health and safety, national reputation, and individual privacy. NCII sectors include the government, defence and national security, transport, healthcare services and energy. (See chart “Who are the National Critical Information Infrastructure (NCII) sector leads?”)

The relevant sector regulator, or NCII sector lead, will formulate appropriate cybersecurity measures, standards and processes to be set out in a document known as the Code of Practice that will apply to NCII entities. There are 208 NCII entities to date, according to NACSA data.

Public and private organisations in Malaysia need to review and consider if they are to be designated as an NCII entity. Consequently, these entities need to assess if their present cybersecurity measures are adequate based on the new requirements under the Code of Practice, says Izwan.

“In accordance with Act 854 (Cyber Security Act), the National Digital Department and the Prime Minister’s Department were appointed as sector leads for the government sector. Both NDD and PMD have designated the respective NCII entities,” says NACSA’s Megat Zuhairy.

“For government agencies that are not designated as NCII, NACSA continues to monitor and provide assistance to enhance their cybersecurity requirements. NACSA also provides threat intelligence and incident response support, while developing cybersecurity frameworks and guidelines.”

All NCII entities must conduct annual risk assessments and undergo audits every two years to ensure compliance with cybersecurity regulations, he says. These audits must be conducted by endorsed auditors and submitted to NACSA for evaluation.

NACSA will be able to conduct random inspections on government and private sector entities to ensure the cybersecurity measures are followed. The audits focus on compliance with the Code of Practice and regulatory standards under Act 854, says Megat Zuhairy.

“The implementation of audits is mandatory for all NCII entities for the systems they have declared as NCII, in accordance with the Cyber Security Act 2024. If their websites and databases are designated as NCII, they should be included in the scope of audits. Based on the Act, each NCII entity is required to conduct an audit at least once every two years,” he adds.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Appellate court upholds quashing of proposed RM86.77 mil fine against Grab, two others

- Affin Bank to distribute Bitcoin fund managed by Halogen Capital

- Malaysian shares dip as investors return from holiday with caution

- Richest woman in Indonesia loses US$3.6b in just three days

- Private hospitals association reject calls for three-year costs freeze, regulation of pharmaceutical pricing

- European stocks dip after Wall Street sell-off, Turkish assets tumble

- FBM KLCI down 0.66% to 1,517.66 on March 19, 2025

- Elderly man claims trial to causing hurt to non-Muslim youth

- UBS sees China property turnaround coming sooner than expected

- India's antitrust raids on global media giants GroupM, Publicis, Dentsu ran through the night