What’s approaching in this serpentine Wood Snake year?

AS the Chinese Lunar Calendar turns a new leaf, we bid farewell to the mythical beast Dragon and embrace the arrival of the enigmatic Snake. Gong Xi Fa Cai to all. This year, the Wood Snake slithers into the spotlight, bringing with it unique energies and opportunities that point to an unforgettable 2025.

The Snake, the sixth animal in the Chinese zodiac, is often associated with wisdom, mystery, and transformation. Those born under this sign are said to be intelligent and intuitive, with a knack for navigating complex situations. Among the prominent figures born in Snake years are former US president John F. Kennedy (1917), India’s first female Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (1917), former Malaysian Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak (1953), YTL Group founder Tan Sri Yeoh Tiong Lay (1929) and Hong Leong Group founder Tan Sri Quek Leng Chan (1941).

While the Snake can be patient and intuitive, the Wood element adds a layer of growth, like the growth of trees reaching for the sky. This year’s transition also coincides with Lap Chun, the traditional beginning of spring in the Chinese calendar. Lap Chun, which typically falls on Feb 4, signals the arrival of warmer weather, longer days, and the start of the agricultural cycle.

Historically, shifts and transformations have marked the years associated with the Snake. But with its blend of flexibility and calculated moves, will the Wood Snake encourage a year of steady growth through patience and planning?

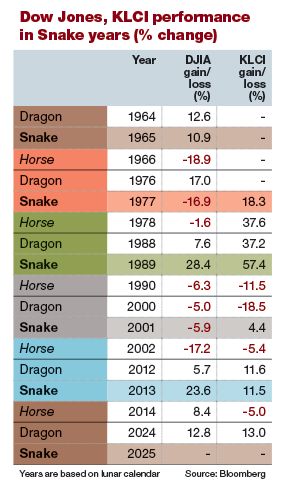

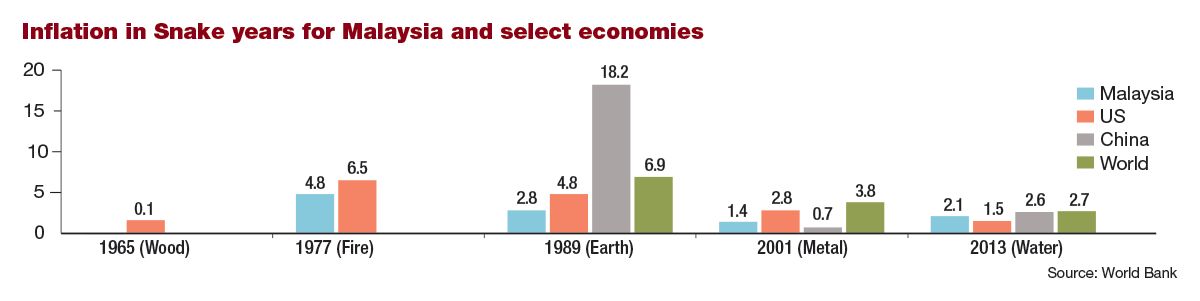

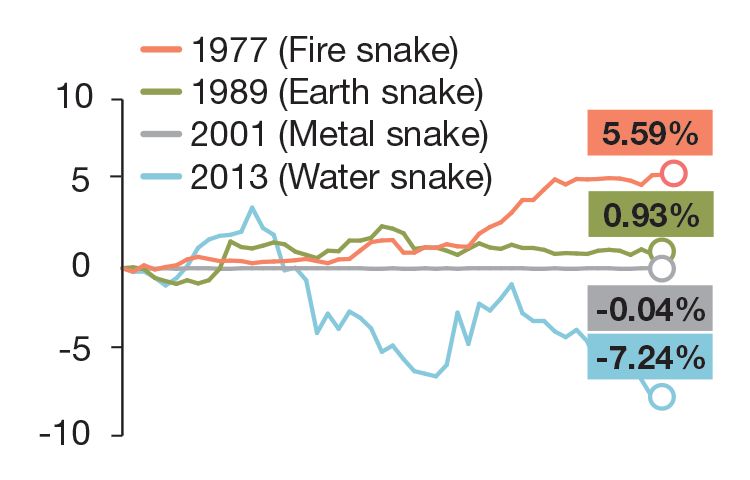

Let’s look back at how the past five Snake years played out — 1965, 1977, 1989, 2001 and 2013 — in terms of economic and social trends, for clues on what lies ahead in 2025.

How past Snake years fared

In previous Snake years, global economic performance and market trends were shaped by both domestic policies and external factors, reflecting the cautious and calculated nature of the Snake.

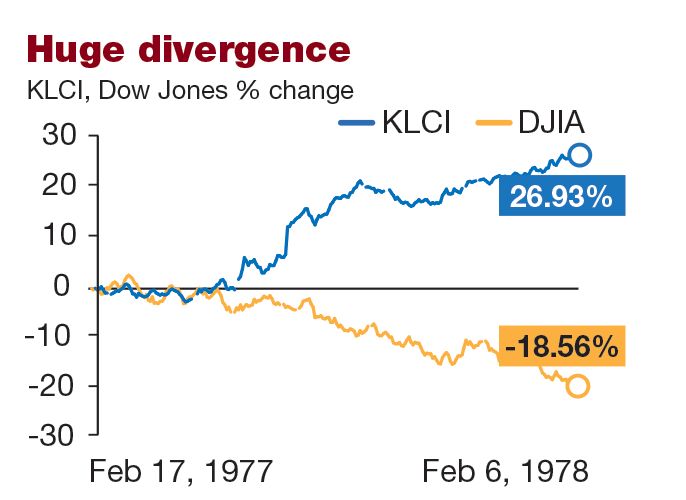

Fire Snake (1977)

Political shifts, technological breakthroughs

The Fire Snake in 1977 came right after Jimmy Carter was sworn in as the 39th president of the US. In India, it was the first time that a non-Congress government — the Janata Party — came to power, defeating India’s first female prime minister Indira Gandhi.

The world also saw technological advances when the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched the Voyager spacecraft to explore the outer planets of the solar system. Apple Inc also introduced the Apple II personal computer, marking its first computer launch aimed at the consumer market.

Tragedy and violence were frequent with disasters like the Golden Dragon gang-related mass shooting in San Francisco, the Taksim Square political violence massacre in Istanbul, and the hijacking of Lufthansa Flight 181 in Europe.

In Malaysia, a state of emergency was declared in Kelantan due to political unrest after the late Kelantan Menteri Besar Datuk Mohd Nasir was removed by the federal government. The country also mourned when Malaysian Airline System Flight 653 was hijacked by unknown persons and crashed in Johor, killing all 100 people on board.

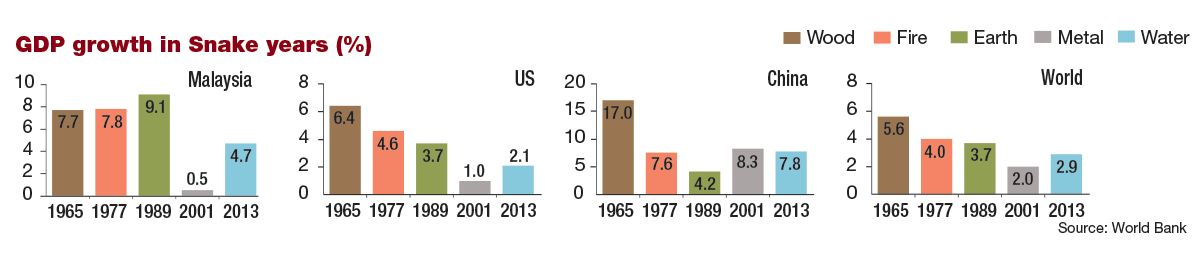

In terms of economic condition, Malaysia’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 7.8% ahead of the global economy’s 4% growth. The US posted a growth rate of 4.6%, and China recorded 7.6% growth.

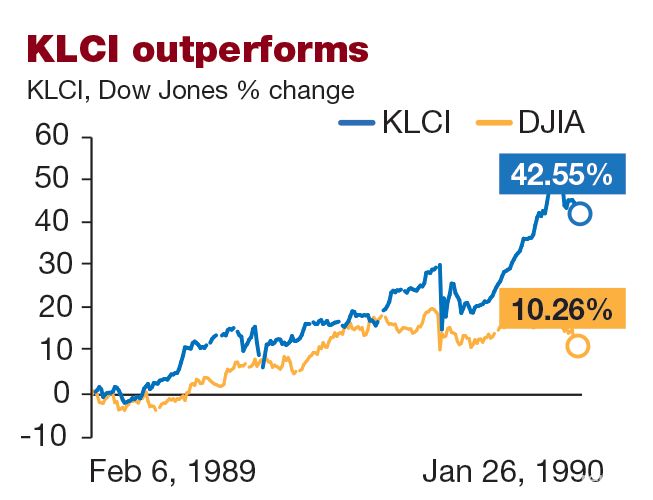

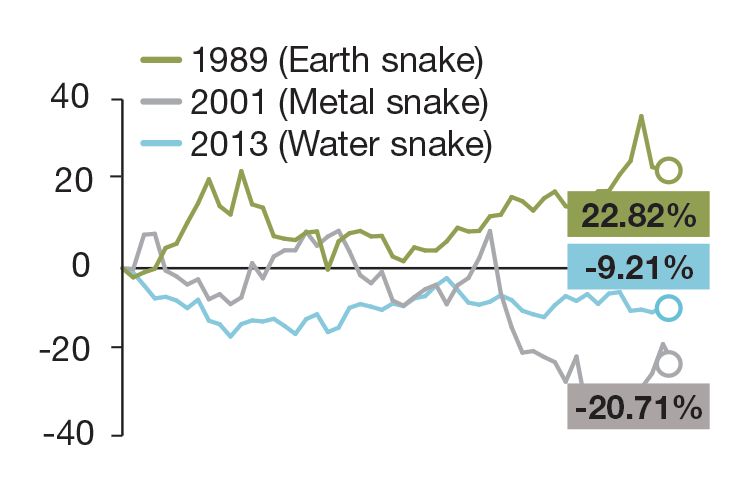

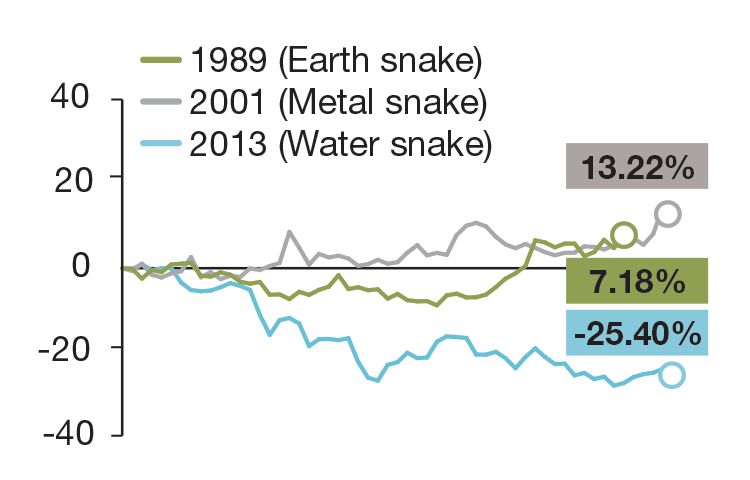

Earth Snake (1989)

End of Cold War, global communism movement

The year of economic growth and global geopolitical shifts saw Malaysia’s economy grow by 9.1%, versus global GDP growth of 3.7%, while the US grew a modest 3.7%. China’s GDP grew 4.2% in the midst of its economic reforms. Inflation in Malaysia was steady at 2.8% well below the global average of 6.9%.

1989 also marked the end of the Cold War; as the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov 9 saw the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the beginning of the end for the Soviet Union. The historic chapter ended at home with the conclusion of the Communist insurgency, marking the dissolution of the Communist Party of Malaya after decades of unrest.

Political unrest however intensified elsewhere, from the Tiananmen Square protests in China to Hungary’s calls for democracy. In Alaska, disaster struck with the Exxon Valdez oil spill, and the Hillsborough tragedy in the UK that claimed the lives of nearly 100 Liverpool football club supporters.

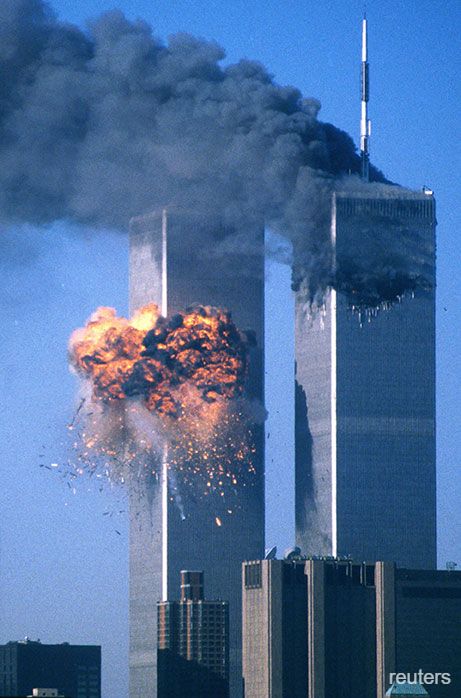

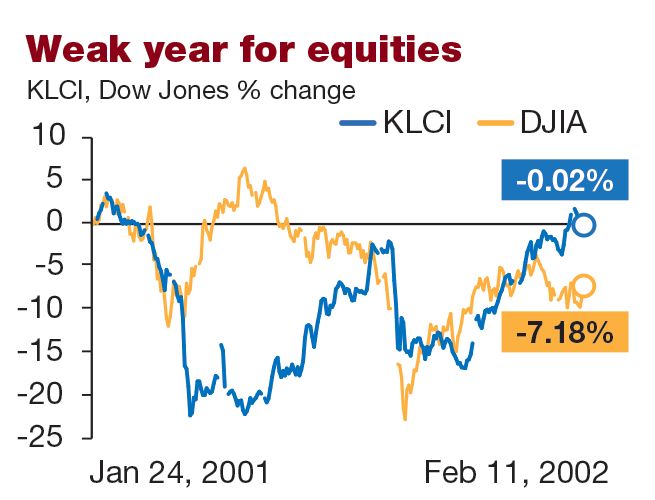

Metal Snake (2001)

9/11 shocks world, China’s global push

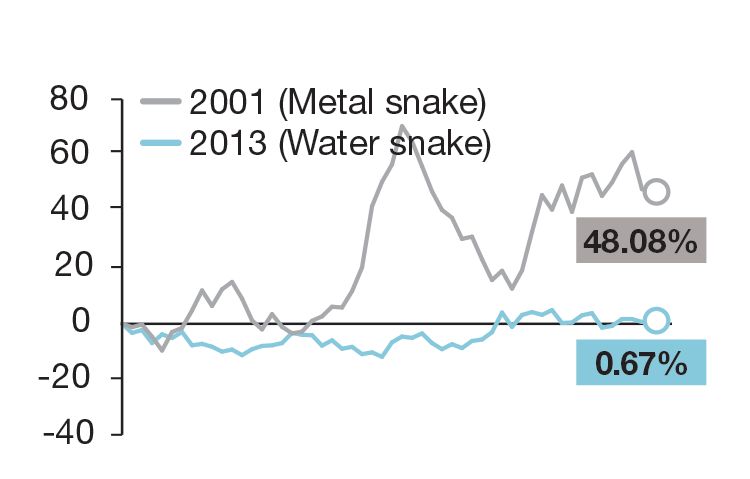

After two cycles of positive Snake years, the Metal Snake year of 2001 saw significant economic and geopolitical challenges which profoundly impacted the world. The global economy grew by a subdued 2% on the heels of the dot-com bubble burst, which led to a sharp decline in valuations and affected markets worldwide.

The aftermath of the Sept 11 attacks in the US caused ripple effects across the globe, including heightened security measures, changes in international relations, and impacts on industries like travel and insurance. The US launched its War on Terror, beginning with military operations in Afghanistan.

Malaysia eked out a marginal growth of 0.5%, dragged by waning external demand. The US economy grew at a modest 1%, while China outpaced most economies with a robust 8.3% growth, followed by China’s participation in the World Trade Organisation (WTO). This marked a turning point for China’s integration into the global economy and its rise as a manufacturing and export powerhouse.

In Europe, the introduction of the Euro as a physical currency began to transform financial systems across the continent.

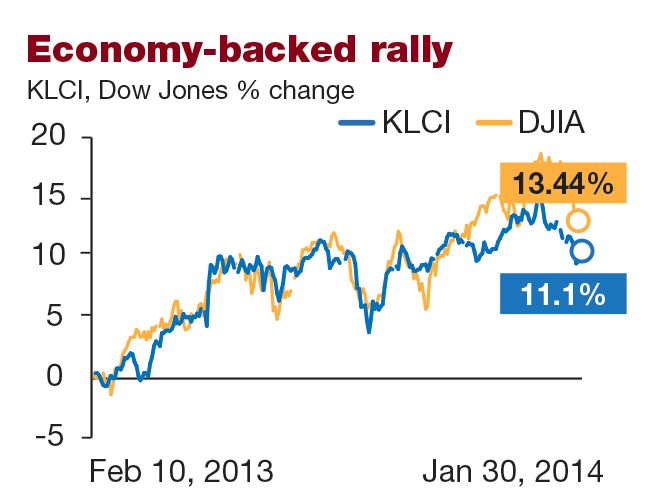

Water snake (2013)

Political continuity and economic recovery

The Eurozone finally emerged from a prolonged recession that lasted four years, while the US under Barack Obama continued its growth trajectory for its fourth year running with stable housing market and declining unemployment rates – although political gridlocks in the US over budgetary issues led to a 16-day government shutdown in October.

Meanwhile, China shifted toward a consumption-driven economy, recording a GDP growth rate of 7.8%. In the Philippines, Typhoon Haiyan ended up as one of the strongest tropical cyclones ever recorded, devastating the country with millions displaced.

At home, Datuk Seri Najib Razak-led Barisan Nasional lost the popular vote in the 13th General Election but stayed in government, with growing urban-rural divide. Najib was sworn in as PM for his second term — similar to the US president Barack Obama.

Ringgit & commodities

divided in past Snake years

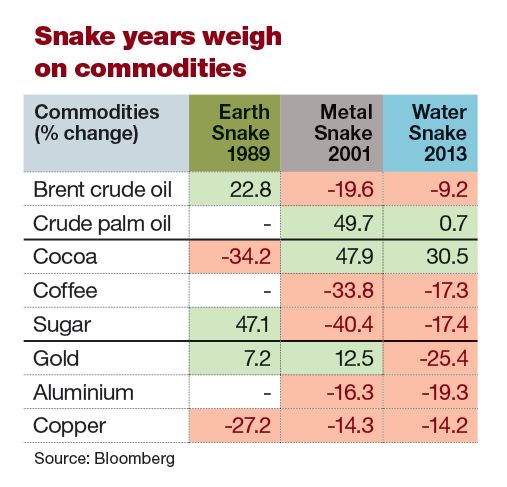

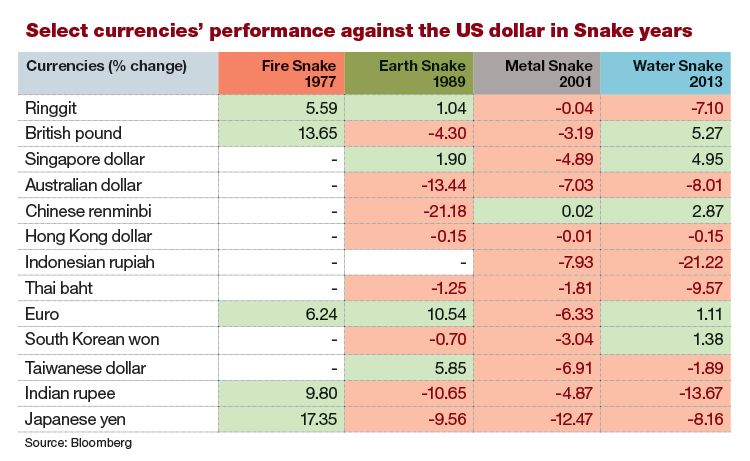

The last three Snake years captured how commodities close to Malaysia like crude oil and palm oil, as well as the ringgit and even gold, went full circle from rapid gains in the 70s to the declines in the 2010s when economic activities peaked and prices retreated from multi-year highs.

Ringgit vs US dollar

The ringgit’s performance against the US dollar in past Snake years varied significantly.

The Fire Snake kept the ringgit stable in early 1977, and the country’s growing oil production and strong exports during the global recovery lifted the currency in 2H.

In 1989, the ringgit was supported by Malaysia’s rapid industrialisation, and export-oriented policies, to brush off its stumble at the start of the Earth Snake year.

In the Metal Snake year of 2001, the ringgit’s performance was still pegged at 3.80 against the US dollar, first imposed after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, and which lasted through the dot-com bubble in 2000, and the Sept 11 attacks in 2001.

The most significant shift occurred in the Water Snake year of 2013, where the ringgit depreciated sharply to 3.04 as the US Federal Reserve (Fed) tightened monetary supply after years of quantitative easing, leading to capital outflows from emerging markets. Declining global commodity prices and the hotly contested GE13 further weakened the ringgit.

Brent crude oil

The Earth Snake slithered and kept oil prices grounded in 1989 at US$15-US$20 per barrel. The conclusion of the Iran-Iraq war and an oversupply of oil from the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and non-OPEC countries led to stable but subdued prices, despite steady global economic growth.

In 2001, the Metal Snake pushed prices slightly higher, ranging between US$20 and US$30 per barrel, as the world grappled with the aftermath of the dot-com bubble burst. The Sept 11 attacks temporarily spiked prices due to geopolitical concerns, forcing OPEC to again step in to stabilise the market.

By 2013, the year of the Water Snake, crude oil price had topped US$100 per barrel. Geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, and global economic recovery further supported the elevated prices. However, the rapid growth of US shale oil production began to put downward pressure on the market, signalling shifts in global oil dynamics.

Crude palm oil

Palm oil prices in 2001 Metal Snake year experienced volatility, averaging at US$250 per tonne. The aftermath of the Sept 11 attacks in the US triggered a global economic slowdown, dampening demand for commodities, including palm oil. Coupled with an oversupply of soybean oil, which competes directly with palm oil in the edible oil market, prices faced downward pressure throughout the year. Additionally, India, the largest importer of palm oil, raised import tariffs on edible oils to protect its domestic oilseed farmers, further limiting demand.

By contrast, the Water Snake year of 2013 saw a much more stable palm oil market, with prices fluctuating within a narrow range, averaging at US$763. The lack of sharp price movements was due to a combination of slower global demand, especially from major importers like China and India, and increased palm oil production in Malaysia and Indonesia. The steady supply helped balance the market, preventing major price spikes. While biodiesel policies influenced palm oil demand, they were not significant enough to cause major price swings. The overall market sentiment in 2013 reflected a maturing palm oil industry that had adjusted to global economic shifts.

Gold

The Earth Snake year of 1989 saw gold prices average US$381.58 per ounce, experiencing a slight decline amid global geopolitical stability and falling inflation rates. The reduced need for gold as a safe-haven asset contributed to the subdued performance during this period.

In the 2001 Metal Snake year, gold prices averaged US$274.14 per ounce, remaining relatively stable despite significant global turmoil. The Sept 11 attacks in the US drove a temporary surge in gold prices as investors sought refuge in the precious metal during heightened geopolitical tensions.

In the Water Snake year of 2013, gold prices fell sharply by 27.7% to around US$1,203.24 per ounce by year-end. This drop was influenced by the US Federal Reserve’s plans to taper quantitative easing, a recovering global economy, and expectations of rising interest rates. The shift towards equities and other riskier assets further weakened gold’s allure.

So, what serpentine energies await us?

According to feng shui consultant Jane Hor, the year of the Wooden Snake — some call it the Green Snake due to the wood element being associated with the colour green — will be slithering in officially on Feb 3 at 10.27pm this year.

It will be a snake that has woken up after a long winter hibernation, so it will be hungry and alert for opportunities. It will bring with it many activities in the first half of the year, requiring lots of effort put in, and the rewards will only come when autumn arrives.

“It is a year of 春播秋收, which literally translates to spring sowing, autumn harvest,” said Hor. It emphasises the importance of diligence, patience, and of course hard work, without which rewards cannot be gained.

But as you bustle about, don’t forget to take good care of your health too, or little illnesses may bog you down, as the year also carries the ‘Number 2 black sickness star’, which is linked to potential health issues, indicating these will be plentiful.

When it comes to investments, Hor advised caution in the first half of the year. “It’s not really a year for bold investments,” she said, adding the market will turn better by autumn. “The lunar months of January, April, July and October will see more fluctuations.”

It is also likely to be another good year for gold, as it is one of the elements that the year’s birth chart or bazi needs. Industries that are likely to fare well are: metal (such as mining, precious metals, with more stability after autumn) and earth (such as plantation, real estate, which will see more improvements and collaborations; mergers possible).

Fire-related industries, such as technology, do not seem as promising or exciting as last year. “No big breakthroughs seen. In the year’s bazi, fire doesn’t seem like a very important element, signifying its role will not be a highlight,” Hor said.

As for water-related industries, such as logistics, they will be less stable, she said, adding players in these industries will need to change the way they do business to sustain their businesses or see improvements. Wood industries, such as plantation or timbre, will be very competitive, with the weak expected to be weeded out.

How about geopolitical tensions, with Donald Trump in power in the US? “I think there’s a reason why the dispute star is in the northwest this year, where the year-breaker is also situated. So there will be lots of disputes, conflict. There might be terrorism problems,” said Hor.

Still, the year will be “smoother, overall”, she said, compared to the previous two, as Trump consolidates his power. “His daughter, Ivanka Trump, may have a chance to ‘come up’ (emerge more prominently) this year, as this is a year that is favourable to women.”

And the good or lucky stars — stars No. 1, 4, 6, 8 and 9, based on the nine-sector flying star formation — are scattered in the southeast, west, south, southwest and east, respectively, Hor noted, indicating that the fortunes of countries located in these sectors will not be bad.

Malaysia, being in Southeast Asia, is also in a favourable location, she said. “Trump’s return seems to benefit us.”

“There are good stars in both east and west, China and the US. But I think China will face more challenges, while the US will be in a more favourable position,” she added.

- Li Ka-shing has little to lose as China threatens Panama deal

- Petronas keeps mum on news of its possible exit from Argentina

- HHRG’s largest shareholders dispose of entire stake at a steep 94% discount

- Pertama Digital, MAG, Axiata, HHRG, KJTS, TT Vision, Catcha Digital

- Retiree loses RM2.3 mil to share investment scam

- Malaysia to fortify position as centre of competitive trade, finance and technology — Anwar

- Op Birth: Detained legal practitioner assisted syndicate in registering birth

- MACC opens two investigation papers involving Sapura Energy

- Schumer retreats on shutdown threat, enhancing bill’s prospects

- Wall St climbs after string of sharp losses as investors weigh tariff impact