This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on January 20, 2025 - January 26, 2025

The narrative surrounding the Orang Asli has often been confined to stereotypical roles such as labourers, craftspeople selling traditional wares or subjects of anthropological studies.

However, this narrative is being rewritten among the communities who live in the villages of Tonggang and Makmur, in the upper Kinta basin of Perak. The indigenous communities there have set up an ecotourism space that is run entirely by the community members.

The Kayuh D’Tonggang ecotourism and recreational site was established in 2023 through a partnership project with the Global Environment Centre (GEC).

“Initially, we planned to open a recreational site as we had activities and natural resources, but we just did not have the funds to do it. Then GEC came in during the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020 and offered to help us set up the place. On Aug 23, 2023, we finally opened it to the public,” says Che Wan Alang, president and tok batin (village head) of Kayuh D’Tonggang in Kampung Tonggang.

GEC, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) dedicated to working on environmental issues, organised a media trip to the villages late last year.

Che Wan tells ESG that the Covid-19 pandemic and the Movement Control Order (MCO) in 2020 devastated the Orang Asli communities, who relied heavily on daily wages and foraging in the forest for survival. Many suburban communities in Klebang Selatan who engage in daily wage activities, such as sewing, contract work and construction, also faced severe economic hardship.

To address these challenges, GEC initiated a community empowerment project under the Hasanah Special Grant 2020 (HSG2020) to create an alternative livelihood for suburban and urban indigenous communities post-Covid-19.

Faisal Parish, founder and director of GEC, says the first phase of the project was to improve and create an immediate alternative livelihood for the indigenous people and address critical river care issues.

“We want to support the Orang Asli community in Kampung Tonggang to develop ecotourism as an additional income generating activity, that draws on their traditional knowledge. We want to empower them and bring back their motivation by recognising their skills and showcasing their knowledge about the forests they have lived in for hundreds of years. They are the rightful guardians of the forests. There is so much they can share with us,” he adds.

With the help of the Ministry of Finance and HSG2020, which amounts to about RM5 million, GEC was able to enhance the facilities and mountain bike eco-trail as well as establish an ecotourism riverside recreation space for the indigenous communities in Kampung Makmur and Kampung Tonggang.

Since its launch, Kayuh D’Tonggang has welcomed more than 3,000 visitors and generated RM50,000 in revenue in its first year, says Che Wan.

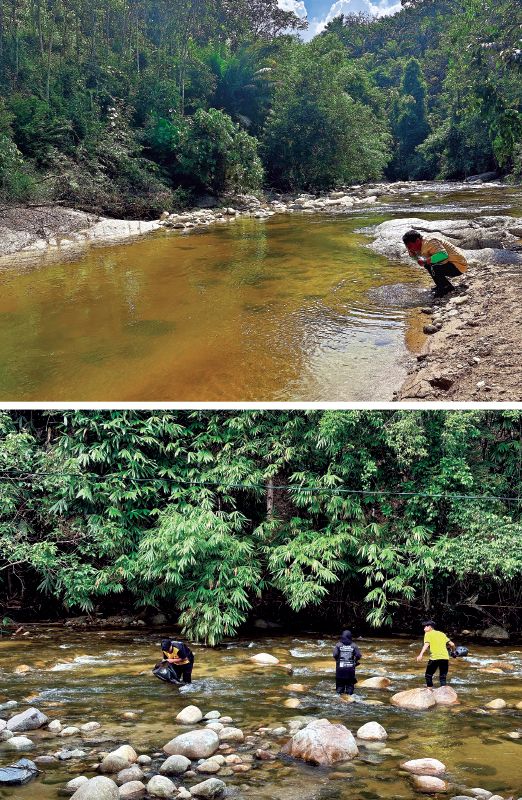

“A unique point of our chalets is that we maximise forest-derived building materials and reduce the use of cement. For instance, we use a specific weaving method using leaves to build the roofs on our chalets. Other than that, we have various activities around the recreational area such as the hunting of wild animals, cultural dances and the Seno’oi river open classroom where we have a sharing session on ecology and river monitoring,” he adds.

Protecting waterways

Kayuh D’Tonggang’s success aligns with GEC’s broader mission of promoting environmental sustainability through initiatives like the River Care Programme, which is supported by the National River Care Fund (NRCF) and Yayasan Hasanah.

The NRCF has channelled more than RM600,000 to support around 75 initiatives and training courses for local communities, community-based organisations, educational institutions and other groups, says Faisal.

He highlights that almost 5% of Malaysia’s rivers are severely polluted, 42% are polluted and 53% of all rivers are classified as clean. This is primarily due to the lack of awareness of the general public about the country’s water resources.

“In 2021-2022, we undertook a joint study of the upper Kinta river catchment, which is critical for providing water supply not only to the Orang Asli but more than half of Ipoh city. Our study showed that there is a massive pollution of the water source from soil erosion from the highway from Simpang Pulai to Cameron Highlands. The highway cuts across the water catchment and the silt washed from the slope has been steadily filling up the Sultan Azlan Shah Reservoir over the last 20 years,” says Faisal.

He adds that every year, Lembaga Air Perak spends millions of ringgit to dig the sediment out of the reservoir but then new silt is washed in.

“We worked with the Public Works Department (JKR) and local Orang Asli community to establish a pilot site to showcase how to plant indigenous plants and trees on eroding slopes to stabilise them. It was successful in stopping erosion — but needs more resources to scale up. In our view, it is much more cost-effective than continually dredging the reservoir.”

To create awareness among the general public, GEC created the River Ranger programme under the River Care Programme, which emphasises water resource management of rivers and river basins. It also involves indigenous youth in looking after the rivers in their villages.

“We have over 30 Orang Asli River Rangers here [at Kayuh D’Tonggang]. They are youth, ranging from 18 to 30 years old, looking after the cleanliness of the river here. The quality of our water has improved since they started monitoring it,” says Che Wan.

The River Care Programme was established in 1998 by GEC to promote and support integrated management of river basins and water resources through nature-based solutions as well as citizen-science approaches.

The NGO established 12 river open classrooms as well as educational centres and hubs that have benefited about 15,000 people through education and conservation activities.

“The River Ranger programme has provided work opportunities for the youth in our village, and they do not have to leave to look for a job. They live here, monitor our rivers and have a job at hand,” says Che Wan.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.