This article first appeared in Forum, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on January 13, 2025 - January 19, 2025

As 2025 begins, the global economy, while stabilising, remains weighed down by familiar risks. China’s recovery is sluggish, Europe’s growth is lacklustre and geopolitical tensions rage on in both the Middle East and Eastern Europe. Yet one threat looms larger than the rest — an old adversary potentially making a disruptive return: the spectre of another round of tit-for-tat trade tariffs that would disrupt global trade once more.

Incoming US President Donald Trump’s renewed fascination with broad-based tariffs presents the most unpredictable and consequential risk for the global economy in 2025. Central to his re-election campaign is a commitment to reshape trade policy through sweeping tariffs, aimed at generating revenue and reshoring American jobs. His administration’s signals of reimposing broad tariffs on imports have already reignited fears of a return to protectionism. It also underscores his intent to make tariffs a cornerstone of his second-term trade agenda, just as he did during his first term when he levied extensive import tariffs on China.

This is not to say that the world in 2025 is not already fraught with significant uncertainties, but the reintroduction of broad tariffs adds another destabilising factor. In the US, the Federal Reserve faces mounting pressure to avoid policy missteps that could trigger a recession. Across the Atlantic, Europe’s economy remains fragile, with weak investment and poor sentiment hampering growth. Meanwhile, China’s efforts to prop up its economy have yet to yield results, weighed down by negative spillovers from a prolonged property sector crisis which dampened investment and consumer demand.

The implementation of tariffs would aggravate these challenges, sending shockwaves through global trade and supply chains — just as they did during the last US-China trade war.

While I do not speak for all economists, economic theory consistently shows that broad-based tariffs create inefficiencies. By imposing taxes on imported goods, tariffs raise prices for consumers and increase production costs for businesses. This results in deadweight loss, which hinders economic efficiency and ultimately benefits no one in the long run.

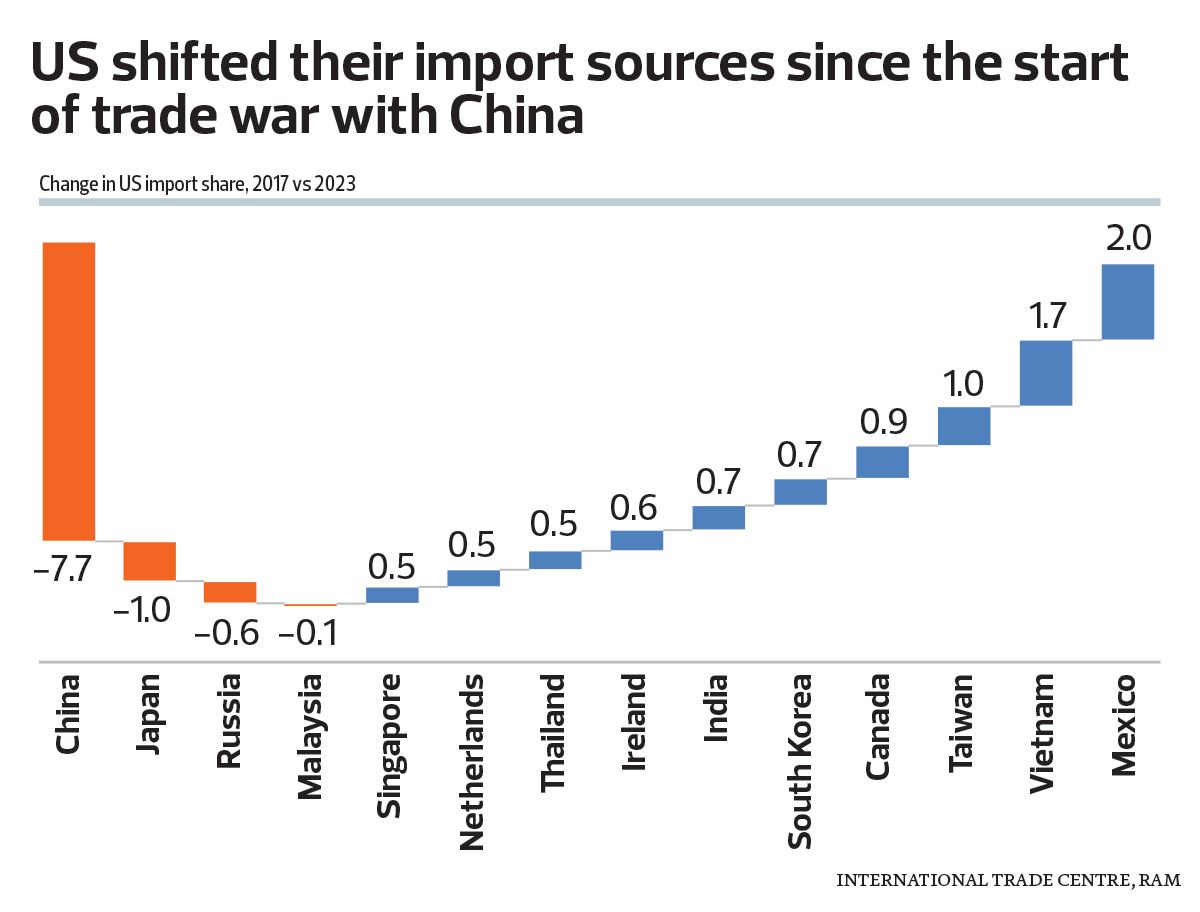

Furthermore, history offers a clear warning. The US-China trade war, which began in 2018, demonstrates that broad tariffs fail to achieve Trump’s intended outcomes of narrowing the US trade deficits and promoting domestic manufacturing. Although the US trade deficit with China narrowed to US$300.2 billion in 2023 from a peak of US$442.4 billion in 2018, the overall US trade deficit ballooned to US$1.15 trillion in 2023 from US$858.9 billion in 2017. Instead of shrinking, imports merely shifted to other countries as supply chains were rerouted. Higher production costs in the US, the unavailability of certain goods locally, and the expensive nature of reshoring production all contributed to these dynamics. Rather than correcting trade imbalances, tariffs burdened businesses with higher production costs and fragmented supply chains, ultimately slowing global trade activity.

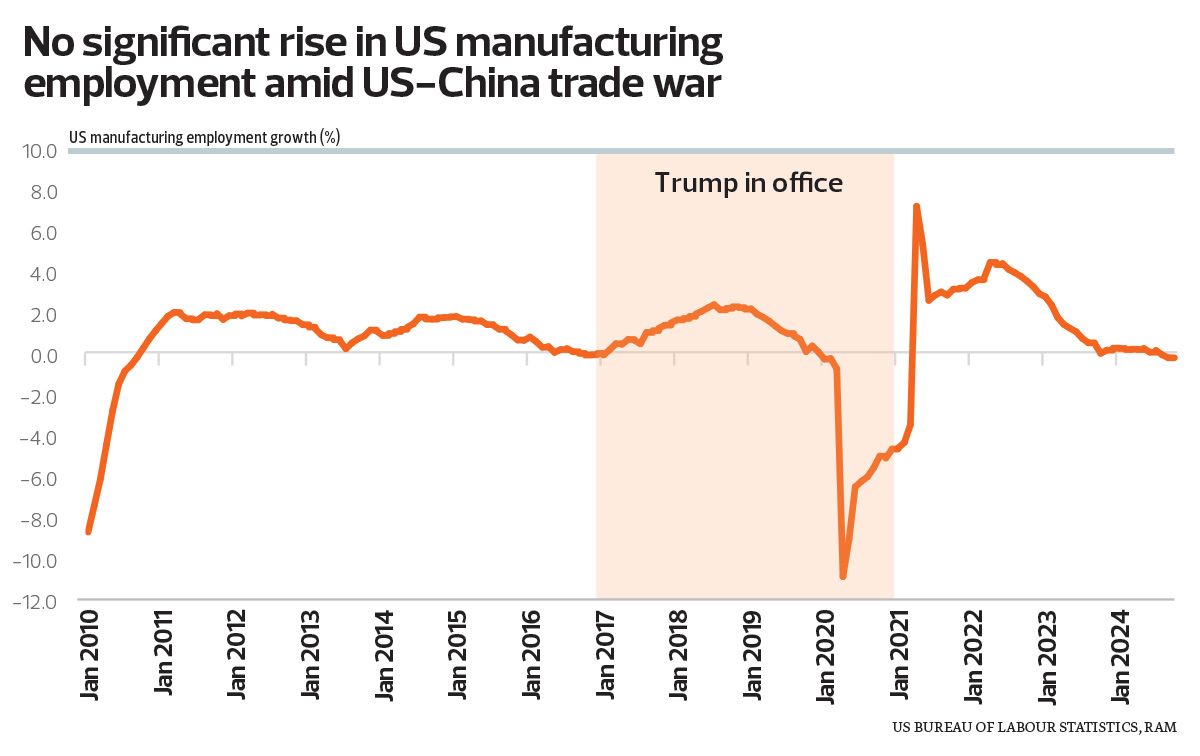

Moreover, Trump’s first-term trade policies did little to spur manufacturing jobs. Data shows no significant rise in manufacturing employment beyond existing trends. With automation and digitalisation continuing to reduce labour demand, the hope for a manufacturing revival appears misplaced. Rather than safeguarding jobs, tariffs led to higher prices and stifled economic dynamism.

This is not to suggest that tariffs are universally harmful. Targeted measures, such as countervailing duties or anti-dumping tariffs, can be effective short-term tools to protect domestic industries from unfair and disruptive competitive advantages that foreign firms may have. However, these instruments are usually targeted and temporary — unlike the broad, sweeping tariffs that Trump proposes.

It may be tempting to view tariffs as a simple means to protect domestic industries or boost government revenue. Yet, as history teaches, the costs often far outweigh the benefits. Revenue from tariffs is minor compared to the economic damage wrought by trade disruptions, diminished competitiveness and inflationary pressures.

The world in 2025 is fraught with uncertainty. Another trade war would be a self-inflicted wound we cannot afford. I sincerely hope that Trump’s affection for tariffs may be more a negotiating tactic than a sound economic strategy. Let us hope the lessons of the past prevail — and that the bogeyman of tariffs stays where it belongs, in the shadows of history.

Woon Khai Jhek, CFA is a senior economist and head of the Economic Research department at RAM Rating Services Bhd

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Malaysia hit with 24% US reciprocal tariff effective April 9

- Malaysia won’t retaliate, will negotiate with US on tariffs — Miti

- Apple production hubs, including Malaysia, hit by tariffs

- Glovemakers rebound as investors see competitive advantages

- Trump’s tariffs on Asean: Nothing to dread, everything to fear

- Gas pipeline fire: 'Home safety first, too early for legal action', says residents' association

- Investors dive for cover as Trump tariffs skittle stocks

- Sarawak to gazette gas corridors to prevent pipeline fire incidents

- Malaysia's semicon firms brace for potential future US action after dodging tariffs

- US coffee drinkers face pricier cup as tariffs hit key supplier Vietnam