Under JS-SEZ, the government’s target is to attract 50 projects within five years, and 100 projects within 10 years. (Photo by Low Yen Yeing/The Edge)

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on January 13, 2025 - January 19, 2025

THE special relationship between Malaysia and Singapore cannot be overstated. However, throughout the decades since Singapore’s expulsion from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, the city state has been viewed as a major competitor to Malaysia when it comes to foreign investments.

While Malaysia, especially its capital city Kuala Lumpur, could have overtaken Singapore in the 1990s, since the Asian financial crisis, the gap between the cities is no longer as narrow as the Johor Strait that separates the two countries.

Singapore has become a major global financial centre, while Kuala Lumpur has to contend with being a regional hub of specialised services, such as Islamic finance and oil palm futures trading.

However, a fact that their leaders cannot deny is that the fates of the two countries are intertwined. While Singapore is a sophisticated financial and trading hub, Malaysia, especially Johor, provides the physical space and manpower that the city state needs to keep growing.

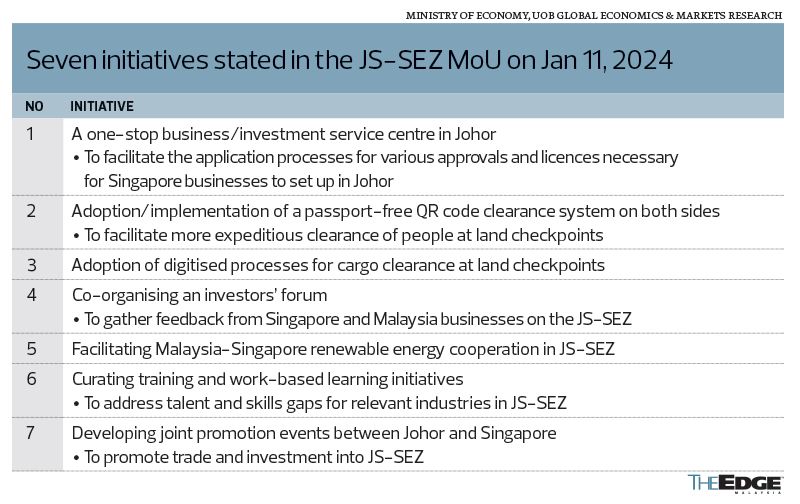

On Jan 6, another step to enhance these ties was taken with the signing of an agreement to create the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone (JS-SEZ) by Minister of Economy Rafizi Ramli and Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister and Trade and Industry Minister Gan Kim Yong.

This is, however, not the first time that Johor has been made a regional centre of growth. In the 1990s, it was part of the tri-state growth region called SIJORI (a portmanteau of Singapore, Johor and the Riau Archipelago, Indonesia).

Then in 2006, Iskandar Malaysia was established, as the government sought to develop economic corridors in various parts of the country.

Southern Johor’s proximity to Singapore and its economic and social links with the city state are often compared with those of Shenzhen and Hong Kong. However, after almost 20 years, Iskandar Malaysia has yet to live up to its full potential.

While investments — both foreign and domestic — have flowed into Johor since the formation of Iskandar Malaysia, they have yet to make the state a regional powerhouse like Shenzhen after the formation of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in the early 1980s.

Will the current iteration of an SEZ within Johor finally transform the state’s economy and help Malaysia make the leap to developed nation status?

“The JS-SEZ has the potential to be transformative, but success will depend on how well the region addresses its challenges and capitalises on this opportunity,” says Imran Nurginias Ibrahim, chief economist at BIMB Securities.

He adds that JS-SEZ formalises and enhances Johor and Singapore’s “natural partnership”, offering the former the opportunity to overcome barriers such as weak connectivity, underutilised infrastructure and governance inefficiencies.

“If executed effectively, the JS-SEZ could position Johor as a major economic hub in Southeast Asia, complementing Singapore’s global stature,” Imran says.

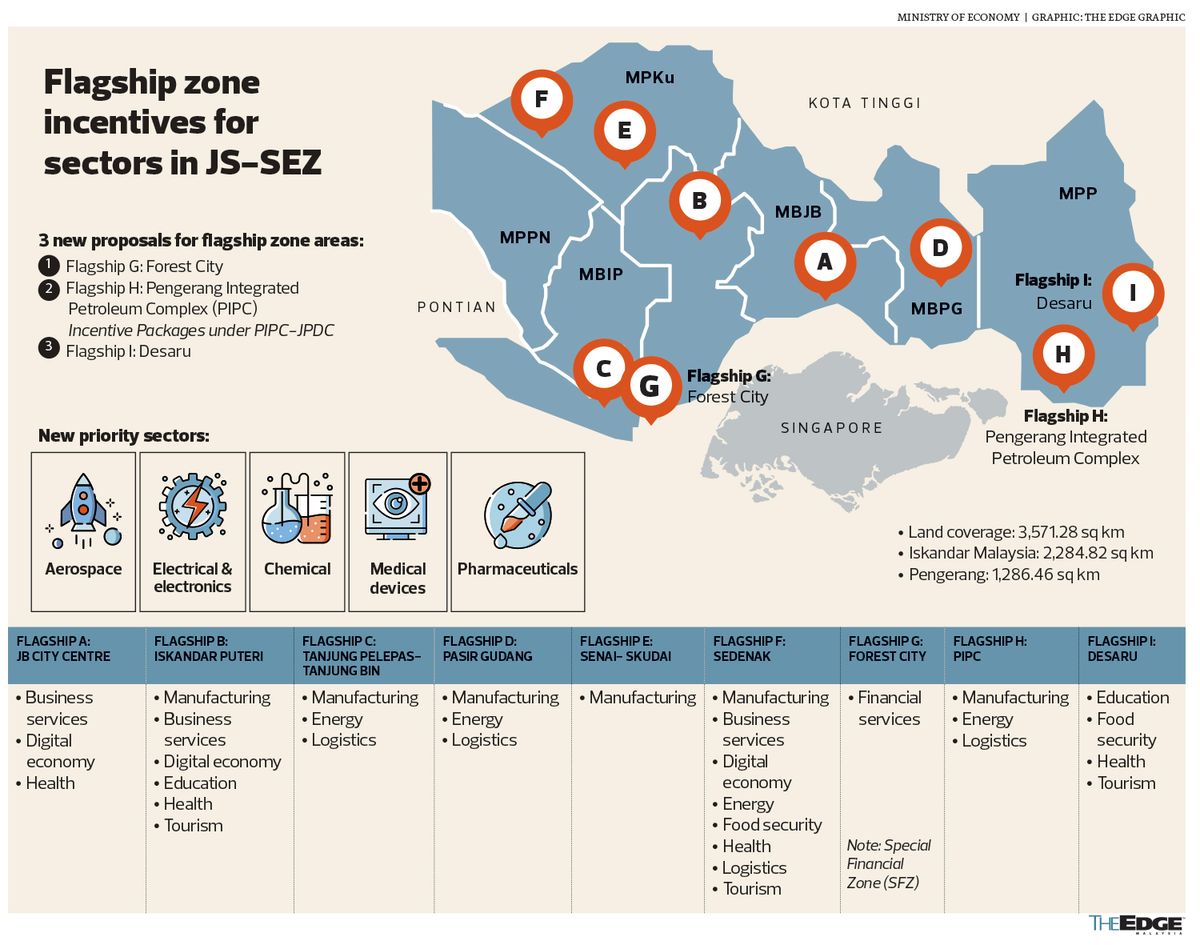

Several priority industries have been identified for the special economic corridor, which is centred on Iskandar Malaysia. On top of Iskandar Malaysia’s six existing flagship zones, JS-SEZ also encompasses Forest City, Pengerang Integrated Petroleum Complex (PIPC) and Desaru.

This adds 1,286.46 sq km into the special economic corridor of southern Johor, on top of the 2,300 sq km under the Iskandar Malaysia initiative.

Under JS-SEZ, the priority industries to be promoted will include aerospace, chemicals, medical devices and pharmaceuticals, in addition to electrical and electronics, petrochemicals and oleochemicals, food and agro-processing, logistics, tourism, healthcare, financial and business services, creative and education, which have been promoted under Iskandar Malaysia.

When the Shenzhen SEZ was established in 1980, the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of Guangdong province, where Shenzhen is located, was only US$321.

In the same year, the GDP per capita of Hong Kong, then a British colony, was US$5,704 — 17.8 times that of Guangdong’s.

By 2023, the gap had narrowed to about four times, as the GDP per capita of the southern Chinese province grew to US$12,622, compared with Hong Kong’s US$52,132.

Nevertheless, comparing Johor with Guangdong is a futile endeavour as both regions are vastly different in almost every aspect. For a start, Johor is a small state compared with Guangdong, while China has a population of 1.3 billion people.

In 2021, the GDP of Guangdong was the highest subnational GDP in all of Asia, at US$1.95 trillion. It is among the largest subnational economies in the world, alongside the states of California, Texas and New York, as well as England.

Even though Johor is positioned as the manufacturing and industrial hub of Southeast Asia, it serves a market of 600 million people which, while significant, is rather small compared with the Chinese market. Plus, Southeast Asia is not a single market.

Unlike Shenzhen, Johor lacks the scale, centralised political focus and access to a vast labour force that were critical to Shenzhen’s rise, notes Imran. Competition with other regions in Southeast Asia that have aggressive SEZ policies and lower labour costs is another challenge for Johor and Malaysia.

So will JS-SEZ be the catalyst that will push Johor to take off, like Shenzhen?

Imran believes that while there are significant differences between JS-SEZ and Shenzhen SEZ, there are opportunities for Johor to become like Shenzhen.

“Johor has several competitive advantages, including its proximity to Singapore, land availability and sectoral focus on high-growth industries like advanced manufacturing, digital economy and green technologies.

“If the JS-SEZ effectively addresses talent development, infrastructure gaps and investor-friendly policies, it could emerge as a major economic hub in Southeast Asia,” Imran says.

He adds that while Johor may not replicate Shenzhen’s trajectory in becoming a global megacity, it can establish itself as a dynamic regional hub that complements Singapore’s global role.

“While the JS-SEZ holds great promise, Johor’s path will likely differ from Shenzhen’s. Success will depend on how well Johor and Singapore align their strengths and adapt to evolving global economic conditions.”

Nevertheless, the objective is for JS-SEZ to accelerate Johor’s development into a developed state within Malaysia. The state government targets to raise its GDP by 7.8% a year to RM260 billion by 2030, achieving developed state status by then.

What makes JS-SEZ different from Iskandar Malaysia?

JS-SEZ is touted as a game changer as this is the first time the Singapore government is actively participating in the development of the region.

For SIJORI and Iskandar Malaysia, proximity to Singapore was just an advantage for southern Johor, rather than being part and parcel of the SEZ. This time around, the city state has skin in the game.

Through the JS-SEZ agreement, the Singapore government will set up a fund to facilitate investments into Johor by Singaporean enterprises as well as multinational corporations (MNCs). However, the size of the fund, how it will be disbursed and the criteria to qualify have yet to be revealed.

On the Malaysian side, fiscal incentives include the Global Services Hub rules, which were introduced during Budget 2024, whereby the level of tax (5% or 10%) depends on the companies attaining operating metrics.

Special corporate tax rates for high growth activities and a special income tax rate for individuals will only be announced at a later date.

“Tax incentives alone are not new in the promotion of the Iskandar region, Kenanga observes, and we opine that for MNCs which have to adhere to global minimum tax standards (15% minimum effective tax) under the Global Anti-Base Erosion (GloBE) Rules, the government may also consider other forms of non-tax incentives,” says Kenanga Research.

The Malaysian government will also set up a fund for infrastructure development in JS-SEZ. The fund will be an allocation to the Ministry of Economy through the national budget. To date, there are no details on the size of the fund.

The Malaysian government’s approach towards implementing infrastructure developments in JS-SEZ is also different this time around. Instead of a top-down approach whereby it decides where and what to develop, it will instead allow investors to identify the most suitable areas.

JS-SEZ is also different from Iskandar Malaysia in that it incorporates Forest City, which has been declared a special financial zone (SFZ) and a duty-free island.

Key incentives for Forest City SFZ include a concessionary corporate tax rate of 0% to 5%, a tax rate of 0% for family offices for 20 years that requires a minimum assets under management of RM30 million, a tax rate of 5% for up to 20 years for financial global business services, fintechs and foreign payment system operators, including mid-office and back-office, as well as a special individual income tax rate of 15% for knowledge workers and Malaysians who work there.

Locally incorporated foreign banks will also enjoy regulatory flexibility to open additional branches within the Forest City SFZ, and benefit from foreign exchange flexibility for offshore borrowing in foreign currency and investments in foreign currency assets.

Other incentives for the Forest City SFZ include special deductions on relocation costs of up to RM500,000, enhanced industrial building allowances of 10%, 10 years’ withholding tax exemption for services and stamp duty exemptions on applicable transactions.

“The SFZ is expected to create and form a new financial ecosystem that is complementary and cooperative with Singapore, similar to the development models of Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Such complementary cooperation will form a financial ‘dual-core engine’ with the potential to drive growth into the rest of Asean,” says UOB.

Unlike with Iskandar Malaysia, the government does not have any specific investment targets for JS-SEZ. Under the initial plan for Iskandar Malaysia, the targeted total committed investments was RM444 billion by 2025.

As at last August, RM413.1 billion worth of investments had been committed into Iskandar Malaysia, of which RM291.4 billion has been realised.

Under JS-SEZ, the government’s target is to attract 50 projects within five years, and 100 projects within 10 years. No specific value of investments has been set.

Under the Iskandar Malaysia initiative, the target is to attract cumulative investments of RM636 billion by 2030. This will overlap with JS-SEZ’s first five-year period of 50 projects.

The government also aims to create 20,000 skilled jobs within the 10-year period. According to Minister of Economy Rafizi, at the end of the 10-year period, JS-SEZ should already reach a critical mass to become a dynamic and robust economic region.

Seamless movement of people and goods key to success

One aspect that has prevented Johor from capitalising on its proximity to Singapore is the congestion at the two crossings — the Johor-Singapore Causeway as well as the Second Link.

According to data by the Department of Statistics Malaysia, monthly arrivals of Malaysians in Singapore exceeded 1.5 million in 2024, with 1.6 million entries recorded in June. The notorious traffic on the two land crossings resulted in the journey taking about two hours in each direction.

The countries are already working on the Johor-Singapore Rapid Transit System (RTS) to ease congestion on the land crossings. The RTS is expected to carry around 10,000 passengers per direction per day and to be completed by December 2026.

However, both countries still require customs and immigration checks on their respective sides.

To ease the movement of people and goods between the two countries, both governments have committed to increasing clearance capacity at their respective border checkpoints, through the implementation of automated immigration lanes and paperless clearance of goods.

They will also study the feasibility of encouraging more commercial vehicles to use the Second Link, explore potential data sharing to enhance customs processes in facilitating cross-border movement of goods, as well as other aspects that could improve the movement.

“The ease of mobility between the two countries is seen by us as a potential way to reduce any talent gap of skilled workers at Johor, although we note that Johor Talent Corporation will seek to address such gaps,” says Kenanga Research.

“Separately, we understand that goods manufactured in the SEZ can be exported either through Johor or Singapore. This could allow more business opportunities for port operators in Johor and we watch for spillover effects to other non-Johor ports as well,” the research firm adds.

There is also the possibility of the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High Speed Rail (HSR) being revived. In addition, a light rail transit system in Johor Bahru has been mooted by the private sector and is supported by the state government.

“I suppose Malaysia needs a spark that would attract foreign and domestic investors at a time when the global economic and market sentiments are pretty much uncertain,” says Afzanizam Abdul Rashid, chief economist and social finance at Bank Muamalat Malaysia Bhd.

“The next hurdle would be how both countries can speed up the implementation knowing that there would be challenges on the regulatory and bureaucracy front,” he says.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Global funds hit pause on Indonesia after Prabowo policy changes

- Trump warns tariffs coming for electronics after reprieve

- Embattled billionaire Ong Beng Seng to step down from Hotel Properties

- Jentayu signs 40-year power purchase agreement for RM2.8b 162MW Sabah hydropower project

- Singapore eases monetary policy as expected, sees weaker growth in 2025

- China's March exports jump in temporary boost as Trump 2.0 heaps pressure

- Stocks rally in Asia as electronics get a tariff break

- Miti: 30 Malaysian firms set for 150 business matching sessions at Expo 2025 Osaka

- Frankly Speaking: After special review, what’s next for YNH?

- Share buybacks in vogue again amid market uncertainty