(Jan 7): Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is resigning after more than nine years leading Canada, bowing to sagging approval numbers and a rebellion within his political party.

Trudeau, 53, currently the longest-serving leader of any Group of Seven (G7) country, announced on Monday he plans to step down as head of the governing Liberal Party. He will remain as prime minister until a new leader is selected, and parliament has been suspended until March 24 while that process is underway.

The winner of the Liberal leadership contest is set to become Canada’s 24th prime minister and will have to quickly prepare for an election, which the Conservative Party is the clear favourite to win, according to public opinion polls.

A national vote is due by October, but it’s likely it will come sooner. The three major opposition parties in parliament have said they will back a motion of non-confidence in the government. If they follow through on that threat, they would bring down the government, and an election campaign would begin.

Trudeau’s political future has been shaky for months, as he proved unable to reverse a slide in his party’s fortunes that accelerated after an inflation shock, and the resulting jump in interest rates, took a toll on Canadian households.

His departure makes him the latest leader of an advanced economy to lose his grip on power. US President Joe Biden was forced to drop his run for reelection, Rishi Sunak’s party suffered a humbling defeat in the UK’s general election, while German Chancellor Olaf Scholz appears set to lose a forthcoming vote.

For Trudeau, the fatal blow was administered by Chrystia Freeland, his longtime deputy prime minister and finance minister. Once one of his closest allies, she stunned the nation on Dec 16 by publishing a stinging resignation letter that indirectly criticised him for “costly political gimmicks” at a time when Canada is preparing for a possible trade war with the US.

Freeland’s exit ignited already smoldering discontent across Trudeau’s party. Dozens of elected members of his own caucus publicly and privately pressed for him to go in the face of dreadful polls.

Potential candidates for the Liberal leadership include Freeland; Dominic LeBlanc, Trudeau’s childhood friend and Freeland’s replacement as finance minister; Foreign Affairs Minister Melanie Joly; and Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of Canada and Bank of England. Carney has become involved in Liberal politics since his return to Canada in 2020, though he has never run for political office before. He’s chair of Brookfield Asset Management Ltd as well as Bloomberg Inc.

The race may also draw others who currently aren’t in federal politics, such as former British Columbia Premier Christy Clark.

‘Sunny ways’

Politics was always Justin Trudeau’s destiny. His first home, in fact, was the prime minister’s official residence: He was born during the first of his father’s four terms in Canada’s highest political office.

When Trudeau took over the leadership of the Liberal Party in 2013, it was still reeling from its worst-ever electoral defeat in 2011 and had lost progressive voters to the left-wing New Democratic Party. Trudeau surrounded himself with young advisers and crafted plans to legalise recreational marijuana, implement a national carbon tax, advance reconciliation with Indigenous people and invest billions of dollars in infrastructure.

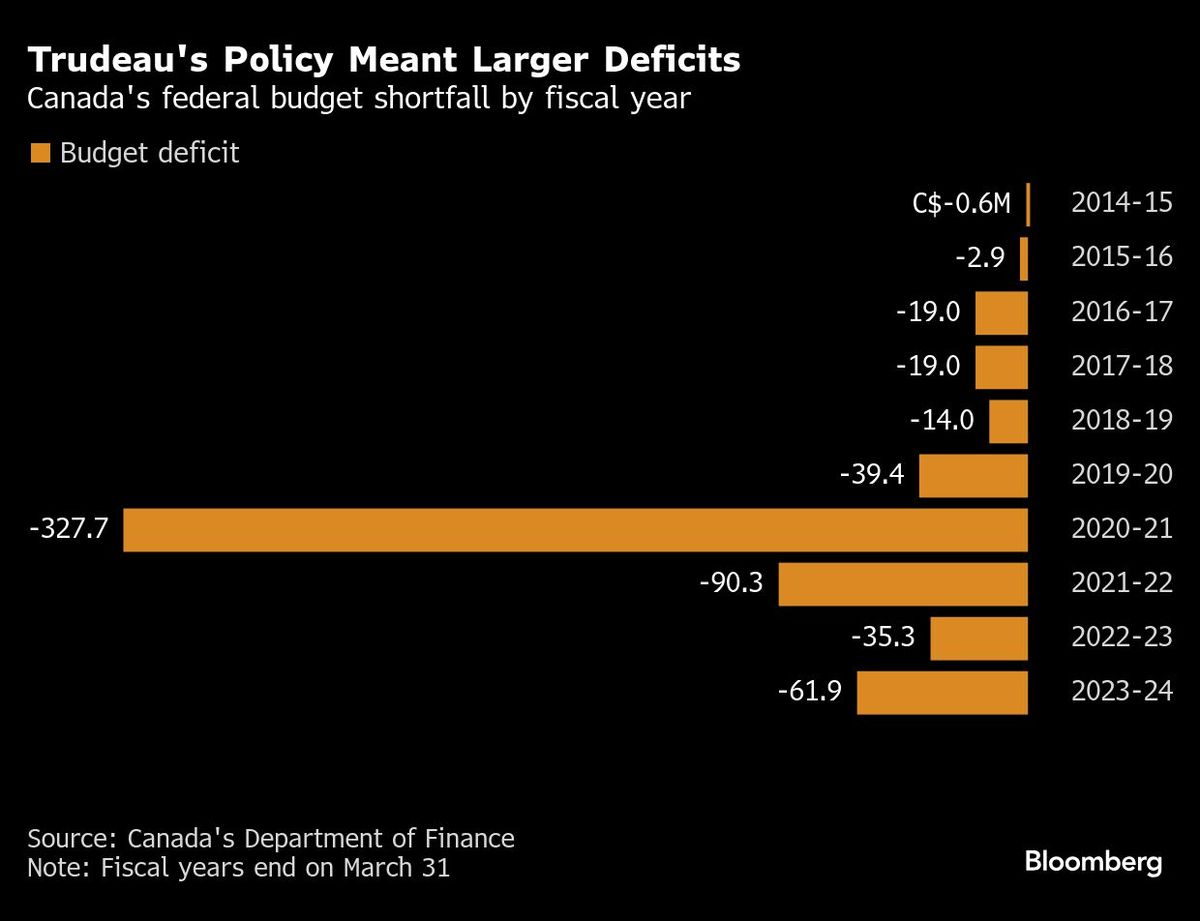

He promised looser fiscal policy — including budget deficits — and programmes to reduce inequality.

Backed by a famous name and a skill for retail politics, he packed rally halls and projected a positive outlook, which he called “sunny ways”. By election day in October 2015, he’d pulled the Liberals from third place to a historic election victory, boosted by strong support from younger voters.

He was the second-youngest person ever to be sworn in as Canada’s prime minister. When he unveiled his first cabinet, it had an equal number of men and women. Asked why, he quipped: “Because it’s 2015.”

Governing proved harder than winning. Oil prices tumbled in the year leading up to Trudeau’s victory, weakening the Canadian economy. Then Donald Trump was elected and threatened to tear up the North American Free Trade Agreement, which had become central to the Canadian market since the 1980s.

Trudeau tapped his trusted lieutenant Freeland to negotiate with the Trump administration. The deal struck in 2018, which kept much of the original trade accord intact, was one of his most important accomplishments as prime minister.

Minority years

But as Trudeau prepared to run for a second term in 2019, his government was rocked by an ethical scandal. SNC-Lavalin Group Inc, one of Canada’s largest engineering firms and a big employer in Trudeau’s home city of Montreal, was charged with fraud and corruption. Attorney General Jody Wilson-Raybould publicly accused key members of the government, including Trudeau’s staff, of wrongly pressuring her to assent to a deal that would resolve the charges.

Trudeau won the October 2019 election, but the Liberals lost their parliamentary majority and finished second to the Conservatives in the popular vote. Much of his remaining years would be defined by the Covid pandemic and its aftermath.

With the economy in freefall in 2020, the government quickly launched massive benefit programmes that ran up the largest budget deficits in Canadian history. Once vaccines became available, Trudeau pushed them hard, then called a snap election in the summer of 2021 in which vaccine mandates were a divisive issue. The Liberals won the most seats, but again lost the popular vote to the Conservatives.

Anger over the government’s Covid rules helped trigger protests in Ottawa and other sites in the winter of 2022. A convoy of truckers occupied Canada’s capital city for three weeks, while other protesters blocked a key bridge that links Ontario and Michigan. Trudeau invoked emergency powers to clear them out. A judge later ruled that move was an overreach.

Although vaccine rules melted away, the pandemic left surging inflation and interest rates, a global phenomenon caused in part by supply-chain snarls and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Canada’s central bank embarked on one of the most rapid rate-hiking cycles in its history. For many homeowners, mortgage payments soared. So did rents.

Cost-of-living concerns quickly swamped Trudeau, despite his government’s expansion of the social-safety net through a child benefit, subsidised daycare and federal dental care.

Some economists blamed the government for keeping the pandemic spending taps open too long, while failing to ensure housing construction was keeping pace with high levels of immigration. Trudeau embarked on a dramatic immigration U-turn in 2024, trying to slow population growth.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives got their house in order. Chastened by three consecutive defeats, they elected a right-wing leader with social-media savvy: Pierre Poilievre, 45. He focused on a small set of economic issues, hammering Trudeau over housing and other affordability issues and fomenting opposition to the Liberals’ carbon tax.

Voters began decisively turning against Trudeau in the middle of 2023, and since then he’s proved unable to reverse a double-digit polling deficit against Poilievre. In 2024, Liberals lost special elections in once-safe Toronto and Montreal seats, as well as a British Columbia swing seat, crystallizing the change in mood.

The New Democratic Party, which had agreed in early 2022 to support the government on key parliamentary votes, pulled out that deal in September.

Uploaded by Felyx Teoh