(Photo by Sam Fong/The Edge)

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 23, 2024 - December 29, 2024

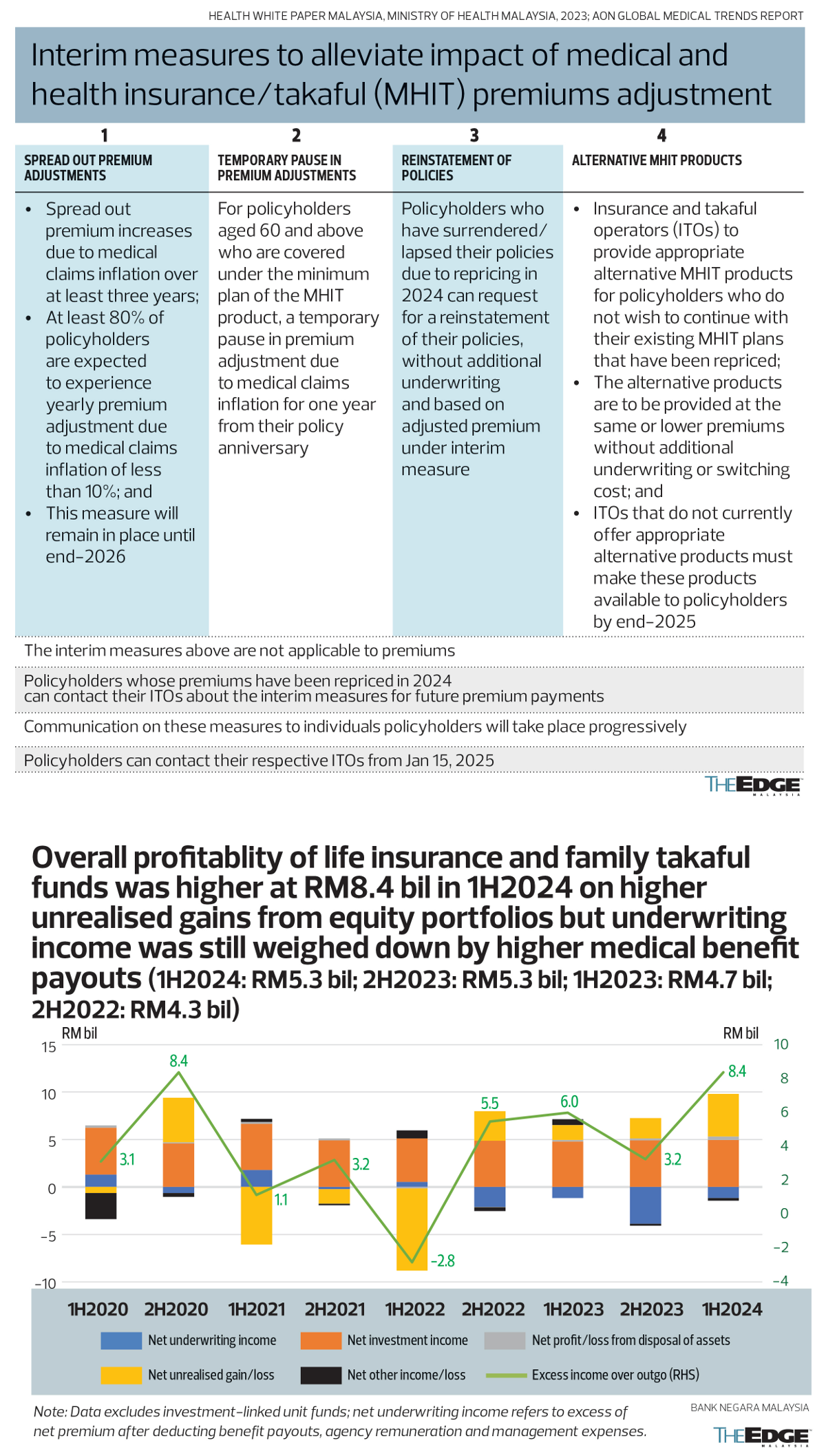

LAST Friday (Dec 20), Bank Negara Malaysia announced several temporary Band-Aid-type measures to quell concerns over current and upcoming medical insurance premium hikes through 2026, pending overdue healthcare reforms to rein in runaway medical inflation and help ensure insurance products stay within reach of most Malaysians.

Instead of the rumoured 40%-to-70% spike in health insurance and takaful premiums, the central bank said at least 80% of policyholders “are expected to experience yearly premium adjustments due to medical claims inflation of less than 10%” between 2024 and 2026, as insurers and takaful operators (ITOs) spread out the changes in premiums arising from medical claims inflation over the period of three years for all policyholders affected by the repricing.

A hike of up to 10% a year over three years for 80% of policyholders keeps open the possibility of previous talk that about 4% of policyholders could end up paying more than 60% more premiums while 5% of policyholders could see a premium hike of at least 40% to 60%, even though 60% (possibly younger, still relatively lower-risk cohorts) will see an increase of only less than 20% in premiums and 30% will see 20% to 40% increases in premiums.

Bank Negara says alternative products with same or lower premiums must be made available to policyholders, who do not want to pay a higher price for existing medical insurance coverage, by end-2025 without additional underwriting or switching costs.

Still, an observer exclaimed in response: “Isn’t [the spreading out over three years] just delaying the pain? I still end up having to pay more for something that I had already been promised when I signed on. How is a lesser product at the same price fair? Why should we pay the price [higher premiums] when actuaries should have calculated the risks [when pricing the product]?”

Indeed, ahead of the announcement of these measures, another observer, who had been notified of a 35% hike in his insurance premium, had said: “There is no real incentive by private healthcare operators or insurers to control costs, is there, if cost increases can be passed on to consumers and policyholders?”

At the heart of these grouses is the pertinent question of whether it is fair to expect consumers and policyholders to bear the brunt of runaway healthcare cost inflation and mispriced insurance products.

Reining in costs

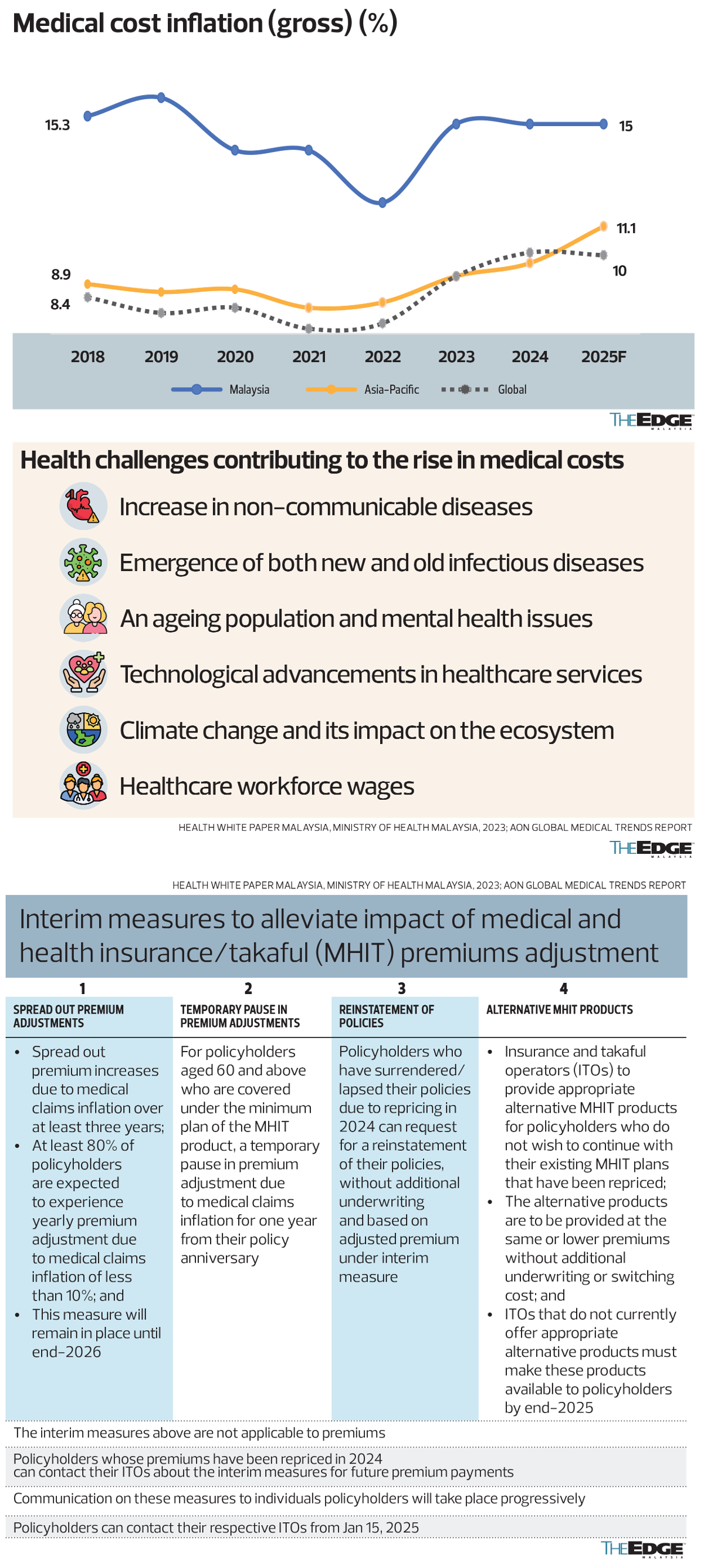

Describing healthcare cost inflation as “runaway” is not an exaggeration. While healthcare-related challenges such as an ageing population, an increase in non-communicable diseases (NCDs), new and old infectious diseases, climate change, as well as technological advancements in healthcare plus higher wages for the healthcare workforce have all contributed to driving up medical costs and the frequency of treatments (and healthcare insurance claims) globally, Malaysia’s medical cost inflation of 15% is noticeably above the Asia-Pacific average of 11.1% and the global average of 10% in 2025.

In its statement dated Dec 20, Bank Negara says: “This rise is driven by factors such as advancements in medical technology and the increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases, which have led to greater demand for healthcare services. As a result, the claims paid out by insurers and takaful operators have grown faster than the premiums collected. While ITOs maintain reserves to cover unexpected increases in medical claims paid, this cannot be sustained if the cost of claims continues to increase beyond reasonable estimates. Hence, periodic adjustments to medical and health insurance/takaful (MHIT) premiums are necessary to ensure that policyholders’ claims can continue to be met.”

Malaysia’s medical inflation rate of 12.6% in 2023 was also more than twice the global average of 5.6%. A source familiar with the numbers says the ringgit’s depreciation has had less of an impact on rising healthcare inflation relative to the pricing of healthcare services, owing to more expensive advanced equipment and medication as well as higher medical personnel costs.

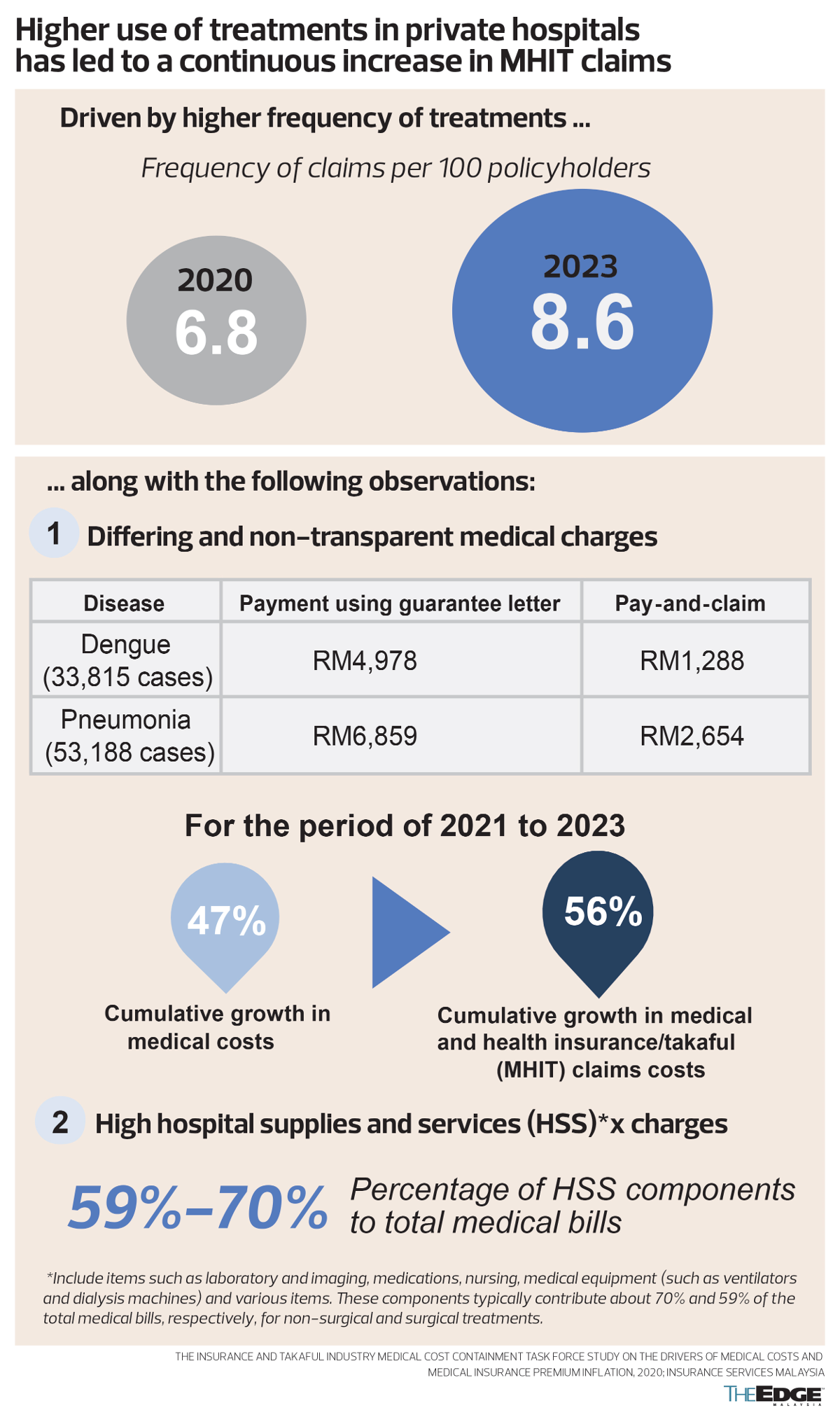

According to Bank Negara, the frequency of claims rose from 6.8 per 100 policyholders in 2020 to 8.6 claims per 100 policyholders in 2023. It is understood that the cost of each private hospital visit rose more than one-fifth between 2020 and 2023, owing to higher prices as well as frequency of treatments.

“High hospital supplies and service charges”, which include items such as laboratory imaging, medication, nursing and medical equipment, “typically contribute 70% and 59% of total medical bills, respectively, for non-surgical and surgical treatments”, according to slides provided by the central bank, which also highlighted “differing and non-transparent medical charges” between patients with and without medical insurance coverage.

Its comparison of a sample of 33,815 patients found insured private hospital patients using guarantee letters charged RM4,978 for dengue treatments, four times more than the RM1,288 billed to “pay-and-claim” patients without medical insurance coverage. Similarly, its sample of 53,188 patients treated for pneumonia saw those with medical insurance coverage being charged RM6,859, or three times the RM2,654 paid by those who foot the bill themselves.

Although implied in the data provided, Bank Negara, in its official releases, stopped short of saying that the pricing of healthcare services should be regulated. As it is, only doctors’ fees are regulated and there are no regulations for other charges by private hospitals, clinics and other healthcare services.

Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim had said in parliament that the Private Healthcare Facilities and Services Act 1998 [Act 586] would be amended next year by the Ministry of Health (MoH) to regulate private hospital charges and implement the diagnostic-related group (DRG) mechanism that recommends a fixed amount or range based on the complexity of a medical procedure, including what a reasonable charge for a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scan should be.

Mispricing or under-pricing

Regulated pricing could well bring down the cost of private healthcare services and, in turn, help reduce the need for higher insurance premiums.

Yet, there is still a need for Bank Negara to ensure that premium increases are not being used to compensate ITOs that mispriced or underpriced products to sell more policies.

It is understood that Bank Negara regulations do not allow premium increases to boost the profits of ITOs. It is not immediately certain, however, whether Bank Negara verifies and ensures that premium increases do not disproportionately target certain groups to avoid paying future claims that ITOs had previously promised to cover when selling the product at attractive (low) pricing to gain market share in the first place.

Also, it is not immediately known what type of policyholders fall under the 4% who could well end up paying premiums that are more than 60% higher and the 5% who could see a premium hike of at least 40% to 60% unless they move to an alternative plan.

Even if premium increases are being allowed due to genuine increases in medical costs and claim trends that could not have been reasonably anticipated when the policy was sold, should the price be borne fully by the policyholder?

The introduction of co-payment products that come with lower insurance premiums, for example, also shifts a significant burden of checking for moral hazard to the consumer who is already stressed by a medical condition.

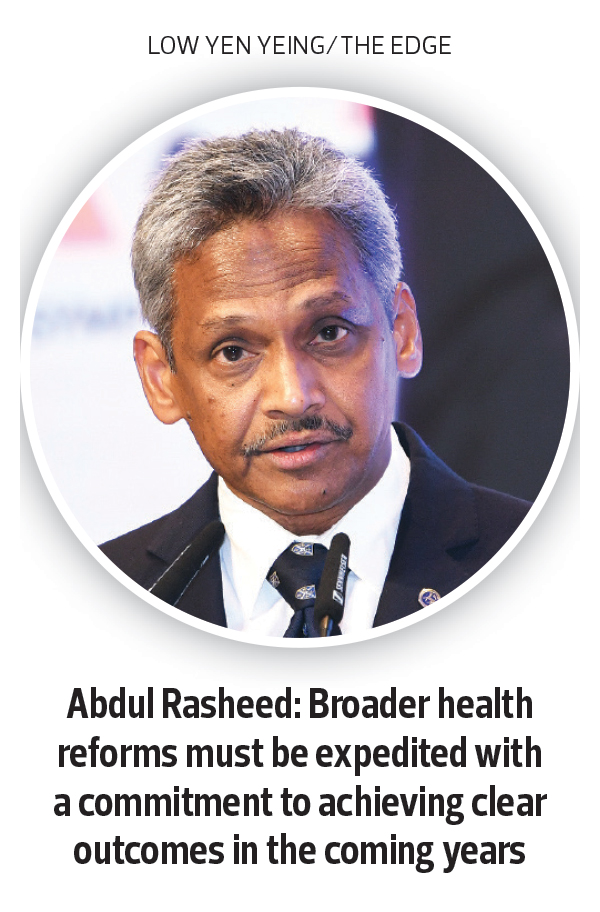

Bank Negara has previously released data showing that higher medical benefit payouts of close to RM20 billion over the two years from July 2022 to June 2024 (RM5.3 billion in 1H2024, RM5.3 billion in 2H2023, RM4.7 billion in 1H2023 and RM4.3 billion in 2H2022) weighed down underwriting income for life insurance and family takaful funds.

Data shows higher overall profitability of RM8.4 billion for life insurance and family takaful funds in 1H2024, which casts a spotlight on the RM60 million jointly committed by the government, ITOs and private hospitals to bolstering healthcare reforms. It is not immediately known how the committed sum compares to the total approved hike in insurance premiums and capacity to cover future medical claims.

It is understood that Bank Negara does not take into account investment income from premiums collected when calculating medical claim losses used to justify the need for a premium hike.

Rather than push through reforms that set the bar higher, most policymakers globally are likely to fall back on the safety of the phrase “international standards” originating from the West, where healthcare, insurance and pharmaceutical lobbies are highly influential forces.

While Bank Negara’s measures did give a one-year moratorium of sorts on premium hikes for policyholders aged 60 and above who are likely to be retired, as it is, the hike might still come unless he or she accepts an alternative (lesser) policy.

Priced out

There is genuine cause for concern, given that policyholders who are priced out of insurance products, especially at an older age, may end up having significantly lower medical benefits and coverage than he or she thought when being sold medical healthcare products that were supposed to have afforded them “peace of mind” on medical charges in their old age.

At press time, Bank Negara, the Association of Private Hospitals of Malaysia, the Life Insurance Association of Malaysia and the General Insurance Association of Malaysia had yet to revert on questions sent by The Edge.

In its statement, Bank Negara rightly surmised that broader measures to address the rising medical costs in Malaysia were urgently needed to manage future premium adjustments and ensure that MHIT products continued to be affordable for the Malaysian public.

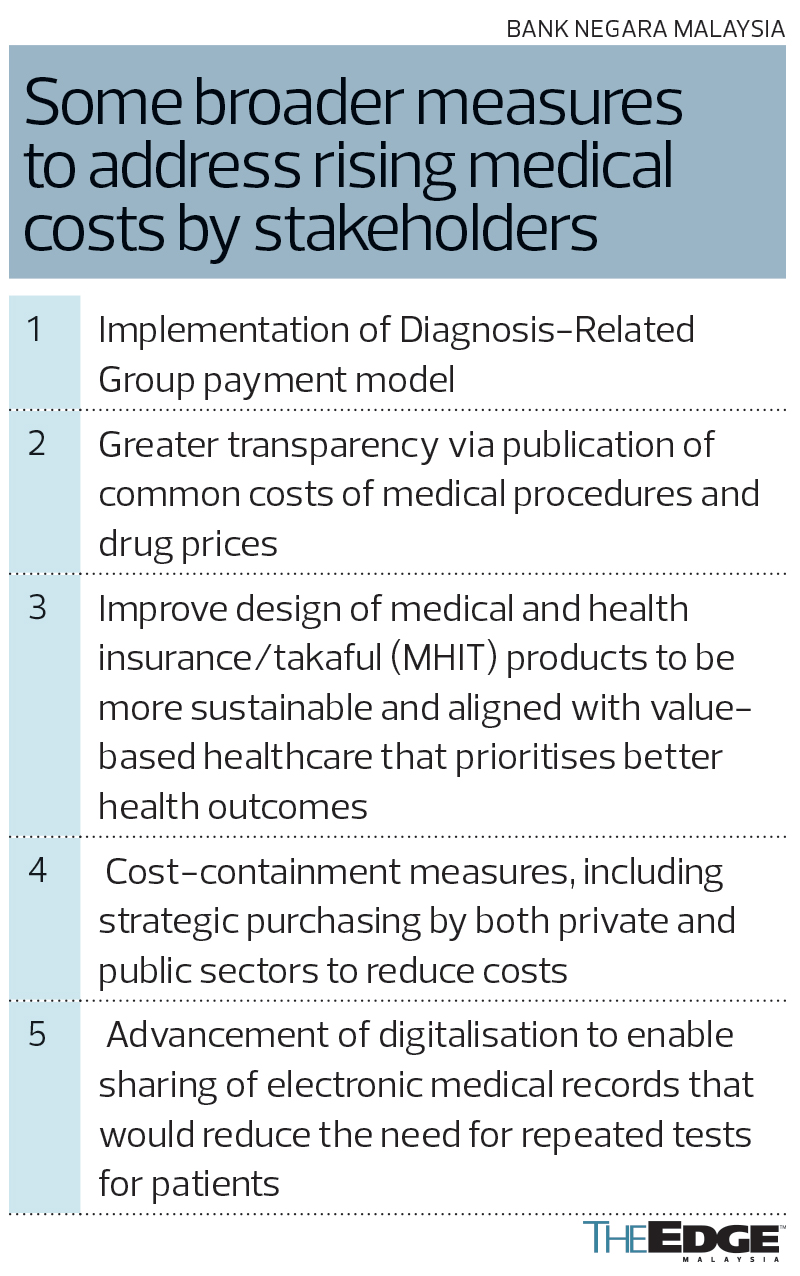

“We need to address the root causes of rising medical and health insurance and takaful premiums, which are driven by higher medical costs and utilisation of medical services. The design of MHIT products must also be improved to make them more sustainable and aligned with value-based healthcare that prioritises better health outcomes. This is a complex challenge that requires the concerted action of all stakeholders across the healthcare ecosystem. These interim measures that we are announcing today will provide some temporary support to policyholders, but broader health reforms must be expedited with a commitment to achieving clear outcomes in the coming years. We are working closely with relevant stakeholders including the Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Health, private hospitals and ITOs,” Bank Negara governor Datuk Seri Abdul Rasheed Ghaffour said in the statement, adding that “all parties have been supportive and committed to working out a long-term sustainable solution to this complex issue”.

It is understood that some seven million Malaysians have some sort of medical insurance coverage, but it is unclear how many have meaningful and sustainable healthcare coverage through old age. A financial literacy survey endorsed by the Financial Education Network in 2021 had found that 42% of Malaysians did not have a medical insurance policy and 13% relied solely on medical cards issued by their employers.

If regulation and execution do not catch up fast enough to rein in healthcare costs, insurance premiums might just need to be revised higher again after 2026. That could drive more Malaysians towards the public healthcare system that is already overburdened and underfunded by a small pool of taxpayers.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.

- Mr DIY founder Tan Yu Yeh relinquishes vice chairman post, to serve as adviser

- China hits back at Trump with tariffs, limits on key exports

- Malaysia refutes 47% US import tariff claim, takes measures to prioritise well-being of businesses and people

- 50,000 Malaysian jobs at risk, business chamber warns as it calls for urgent US tariff mitigation council

- Trump hits China tariff retaliation, says policy will remain

- ‘Worst-case scenario’ for tech wipes $1.4 trillion from Nasdaq

- Anwar says impact of latest US tariff on nation's economy still being assessed

- Tok Mat, Rubio discuss bilateral relations, Asean-US Special Summit date

- US solar’s hoarding habit will help blunt sting from Trump tariffs

- Wall Street rout drags Nasdaq near bear market