(Dec 22): Emerging markets (EM)-focused investors have had little to celebrate over the past year. Or for that matter, over the past decade. Now the prospect of Donald Trump’s tariffs and trade wars has some considering abandoning them altogether.

From stocks to currencies to bonds, 2024 was yet another year in which the asset class failed to live up to its promise, or to the hype of money managers tasked with promoting riskier assets in smaller markets. For some, like London-based hedge fund Broad Reach Investment Management, the best opportunities in emerging markets come from betting against them.

Others are starting to wonder if it’s worth getting involved at all.

“It’s no surprise investors want to throw in the towel on emerging markets, or quit trying altogether,” said Sarah Ponczek, a financial advisor at UBS Private Wealth Management’s BV Group, which manages more than US$3 billion (RM13.52 billion). “You can talk about the eventual benefits of global diversification, but increasingly, all anyone wants to talk about is AI (artificial intelligence), the S&P 500, and seven mega-cap tech stocks that have been all the rage.”

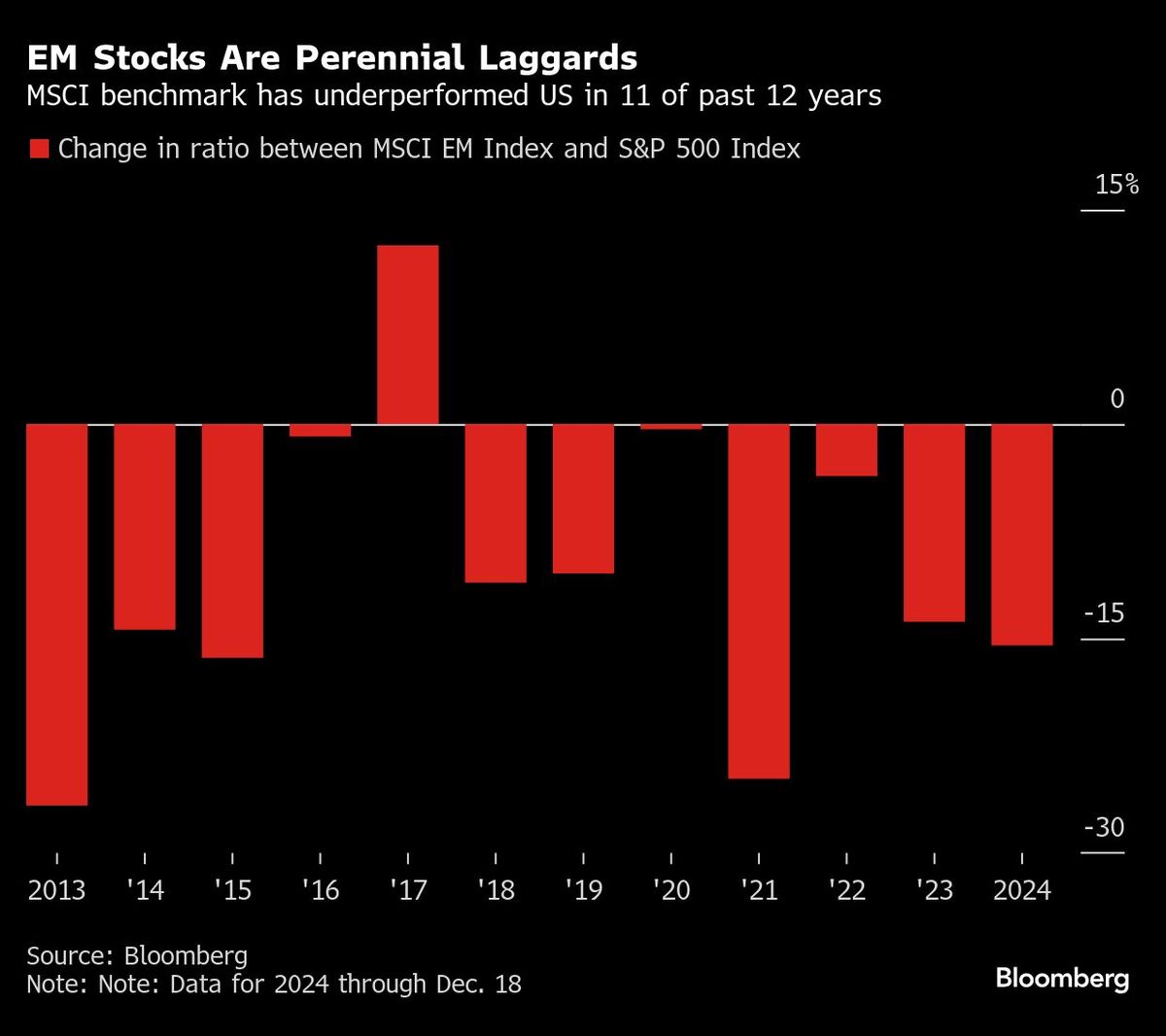

While a handful of frontier markets such as Pakistan, Kenya and Sri Lanka posted turnarounds this year, no major emerging market outperformed the US stock market in 2024. The benchmark MSCI EM index was up less than 5% on the year as of the close on Friday, trailing the S&P 500 for an 11th of the past dozen years. Over that period, US equities have handed investors about 430% in total returns, 10 times what EM stocks have delivered.

At the core of EM struggles is the inability of most countries to get ahead of the US dollar. JPMorgan Chase & Co’s index of EM currencies is heading for a seventh successive year of losses. In 2024, all major EM currencies have lost value against the greenback, save the South African rand and the Malaysian ringgit. At least nine have posted slides of 10% or more.

With Trump pledging to impose tariffs against EM countries from China to Mexico, Broad Reach’s chief executive officer Bradley Wickens said such losses are likely just getting started. He said earlier this week that he’s excited about opportunities in EMs for next year — mostly because he thinks there are profits to be made in shorting them.

“It is difficult because if the US is considered the safe haven, not just from the currency but also from the equity perspective, it’s really hard to turn against a tide because people disregard valuations,” said Dina Ting, the San Mateo, California-based head of global index portfolio management at Franklin Templeton.

Things are hardly any better for fixed-income investors. Since October 2023, as global money managers began positioning for an eventual pivot to interest-rate cuts by the US Federal Reserve, many have been betting on an outperformance in EM local-currency bonds on the grounds that lower US rates would support rate cuts in developing nations.

That’s gone wrong in two ways: First, many EMs have been unable to start or continue their own easing cycles due to persistent inflation fears, as well as newer threats such as Trump’s tariff plans. Second, local bonds have also lagged safer assets in developed markets.

Investment manager Grantham Mayo Van Otterloo & Co, or GMO, earlier this year touted local-currency EM debt as a “once-in-a-generation” buying opportunity. But local-currency EM sovereign bonds have returned just 2% this year, according to a Bloomberg index tracking them, underperforming alternative fixed-income assets, such as US corporate high-yield bonds, which have returned 8%.

Luis Oganes, head of global macro research at JPMorgan, said hopes for an end to three years of outflows from EM-dedicated funds were stirred when the Fed started cutting in September. But they ended with Trump’s election in November. So far this year, EM-dedicated bond funds have registered US$23 billion in outflows, according to Bank of America, citing EPFR Global data.

“We were hoping that 2025 would be the return of capital flows into emerging markets, but given this uncertainty, even if the Fed starts to cut, it is unlikely,” Oganes said. Now, “we are expecting outflows from EM-dedicated funds” and “Fed cuts won’t be enough” to bring them back.

All this is leading to some increasingly awkward conversations on Wall Street, and other centres of global finance.

“The best way to end a conversation with asset allocators and investors is to start talking about emerging markets,” said Xavier Hovasse, Paris-based head of emerging equities at Carmignac, a US$34 billion firm. “A lot of people have thrown in the towel after years of underperformance.”

Some EMexperts are finding creative ways to circumvent the perennial disappointment in EM performance, such as gaining exposure to EM growth, not via EM stocks, but via US multinationals. That’s the strategy deployed by Lewis Kaufman, whose Artisan Developing World Fund was technically the world’s best-performing EM stock fund for much of this year, after he loaded up on US stocks like Coca-Cola, Apple and Nvidia.

“If you’re a US investor, the signal you’ve been getting over really long periods of time is don’t diversify outside of the US,” said Barry Gill, New York-based head of investment at UBS Investment Management Americas. “And if you’re an international investor, the only signal you’ve been getting from the stock market perspective is if you’re going to diversify; the only thing that’s going to be really valuable to you is the diversification into the US.”

It hasn’t always been that way.

Between 2000 and 2010, a booming Chinese economy and globalisation of supply chains boosted EMs and juiced returns for investors, gaining 359% compared with 59% for developed-market stocks and 31% for US stocks.

Ting at Franklin Templeton is among those betting that those days are bound to return.

“If you look at the size of the US versus everything else, I mean, it’s not warranted to be like that,” she said. “Rational investors may not want to put all their eggs in one basket.”

Wim-Hein Pals, managing director and head of emerging markets at Robeco Institutional Asset Management, which has €204 billion (US$212 billion) under management, concurs.

Trump’s threat around new trade wars is already introducing uncertainty into developed markets as well, Pals said, as evidenced by the Fed’s indications this week that it will likely pursue a more restrictive monetary policy than previously envisioned next year.

“US equities, and some of these other asset classes, are way overvalued,” Pals said. “Don’t put all your eggs in 2025 in the US basket.”

What to watch

- China’s business surveys and inflation reports from Asia, including South Korea, are highlights in the data releases scheduled over the next two weeks; China’s official business surveys are likely to show a recovery remains mostly elusive in December despite stronger stimulus; data is set for Dec 31.

- CPI (consumer price index) reports are also due in Singapore, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Indonesia, where inflation likely moderated in December, largely due to base effects.

- South Korea will release industrial production data on Dec 30.

- Pakistan will release GDP (gross domestic product) numbers; GDP growth likely slowed to 2.4% year-on-year in the third quarter (3Q), from 3.1% in 2Q2024.

- Türkiye’s central bank is expected to cut interest rates on Dec 26; Bloomberg Economics sees the CBRT (Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye) taking the one-week repo rate to 48.5% on Dec.26, from 50%.

Uploaded by Liza Shireen Koshy