This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on April 1, 2024 - April 7, 2024

WITH air travel rebounding to 2019 levels, airports around the world are at their busiest since the Covid-19 pandemic, but flight cancellations and delays, hours-long queues and mishandling of baggage are causing passenger frustration and drawing media attention.

In Malaysia, a recent decision by the aviation industry regulator Malaysian Aviation Commission (Mavcom) to impose a new passenger service charge (PSC) on those taking connecting flights at Malaysian airports and make revisions in the departure PSCs from June 1 has prompted renewed calls for service levels at the country’s main gateway, the Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA), to be raised.

From June 1, international travellers on connecting flights at KLIA Terminal 1 (KLIA1) will pay a transfer PSC of RM42, and RM29 at KLIA2 and other airports in the country, whereas domestic travellers on connecting flights at all airports in the country will pay a transfer PSC of RM7. Passengers flying to Asean countries will pay the same rate as their international counterparts — RM73 for those flying out of KLIA1 and RM50 from KLIA2 and other airports, from RM35 currently. The domestic PSC will remain at RM11 for all airports in the country.

Datuk Chandran Rama Muthy, CEO of Batik Air, a Malaysia-based full-service carrier with its main hub at KLIA1, says with the increase in rates for passengers at KLIA, it would like to see a higher standard of service for the use of the facilities. “[We] hope to see issues such as congestion addressed in order to offer an excellent passenger touchpoint experience,” he said in a statement following the announcement.

Transport Minister Anthony Loke also reportedly admitted to weaknesses in KLIA and said Malaysia Airports Holdings Bhd (MAHB) was improving the aerotrain system and baggage claims at the airport to ensure quality service.

According to Pushpalatha Subramaniam, director of consumer and public affairs at Mavcom, which regulates aeronautical charges and quality of service (QoS) at all commercial airports in the country, Mavcom has implemented an effective mechanism to closely monitor service standards at airports.

“There are measures in place to monitor the service quality of airports via our airports QoS framework, which was first introduced in 2018,” Pushpalatha tells The Edge in an interview.

She says airports can be fined for failing to meet the QoS standards.

Monitoring is currently being done at KLIA1 and KLIA2, Kota Kinabalu International Airport and Langkawi International Airport.

Pushpalatha adds that the implementation of the QoS scheme at Sultan Abdul Aziz Shah Airport (Subang Airport) in Subang, Selangor has been held back due to the changes in the Subang Airport Regeneration Plan (SARP), whereby the government is allowing scheduled commercial jets to operate again at the airport. “We were making preparations to implement the scheme in 2023. We had undertaken development work on Subang Airport based on the existing infrastructure. The QoS scheme will be introduced once MAHB has firmed up the SARP.”

In the meantime, the commission plans to roll out the scheme at four more airports — Kuching International Airport, Senai International Airport, Penang International Airport and Miri Airport — by the fourth quarter of this year. Its target is for the remaining airports in the country to implement the QoS scheme progressively until 2027.

“We are now in the development phase and engagement with the airport community is being done,” says Pushpalatha, who leads the development of the airports QoS framework.

A total of 81.9 million passengers passed through the 39 airports managed by MAHB in Malaysia last year. This is 78% of the 105.2 million travellers who used the airports in 2019. The number of passengers travelling through KLIA1 and KLIA2 reached 47.2 million in 2023, which is 76% of the 62.3 million travellers in 2019.

Airport Council International (ACI) World, an organisation of airport authorities, expects passenger numbers in the Asia-Pacific region to surpass 2019 levels by 3% by the end of this year — the first time it has exceeded 2019 levels since Covid-19. ACI also forecasts that the global passenger numbers for 2024 will exceed that of 2019 by 6% and increase by 12% compared with 2023.

Pushpalatha says in 2016, when Mavcom was developing the QoS framework, it had reviewed performance data provided by MAHB and conducted a benchmarking exercise of service quality at other international airports of KLIA’s size category, which is 30 million passengers per year.

“We also carried out consultation exercises with stakeholders, including all principal airlines and airport operators, in late 2016, with a follow-up in April 2017. We did not pluck the service quality elements to be included in the QoS scheme from the air,” she stresses.

Pushpalatha believes the QoS framework is effective in lifting the service levels of airports. She says a case in point is Langkawi International Airport, which received ACI’s airport service quality award for best airport of two to five million passengers in Asia-Pacific in 2023, its third straight year of winning the award.

MAHB, which manages 39 of 42 airports in Malaysia, has been handed a penalty of RM2.9 million for quality performance failures so far. These penalties were incurred for not meeting the targets on cleanliness of washrooms, availability of ramp WiFi service and baggage arrival time.

Pushpalatha maintains that the main objective of the QoS scheme is to ensure consistent performance and not to penalise airports.

“We are driving efficiency across the country’s entry points. We assess airport service levels based on specific measurement mechanisms. There is no ambiguity on how we obtain these results. The performance monitoring is objective,” she says.

She believes that KLIA1, which opened in 1998, can regain its position among the world’s top 10 airports. “We can, but there is a lot of work that needs to be done at the airport. For one thing, the major asset replacement programme has to be completed. The aerotrain system shouldn’t have failed in the first place if you have your internal processes in place, where assets need to be replaced at a certain time. To me, we could have avoided it.”

The following are excerpts from the interview:

The Edge: Ahead of the imposition of the new transfer PSC and the revised departure PSCs in June, how does Mavcom ensure that airport service levels will be maintained?

Pushpalatha Subramaniam: We have in place the airports QoS framework, which was developed in 2016 in line with a revision to the departure PSCs. Because we are responsible for announcing the PSCs, it is also our role to make sure that service standards at the airports are on a par with global standards. We had done extensive groundwork before we came up with this framework. We undertook consultation exercises with stakeholders, including the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and the airport community in 4Q2016 and throughout 2017. We also reviewed the performance data provided by airport operators. They also have their own set of data, like how long does it take to dock the aerobridge by the aircraft door after landing. But some of the data that we had obtained was done subjectively. What we wanted was objective data — everything must be automated. So we also drove technology-driven data from airport operators so that there is no ambiguity.

[When developing the QoS scheme], we also conducted a benchmarking exercise to review the QoS regimes in place at a number of regulated airports around the world. The countries that we looked at were Australia, Brazil, France, India, Ireland, Portugal and the UK. Then we issued a consultation paper, which was published on Mavcom’s website in July 2017, to seek public feedback on the proposed QoS scheme. With all these, we made sure that the QoS scheme is relevant to Malaysia.

The airports QoS scheme was first implemented at KLIA1 and KLIA2 in September 2018.

What does the airports QoS framework entail?

We are very clear in our objective that we wanted to enhance passenger comfort at the airports, ensure customer service levels are prioritised, and facilitate improved airport user experience. We didn’t do this scheme just for the consumers but for the airport community such as airlines, ground handlers, immigration and customs as well.

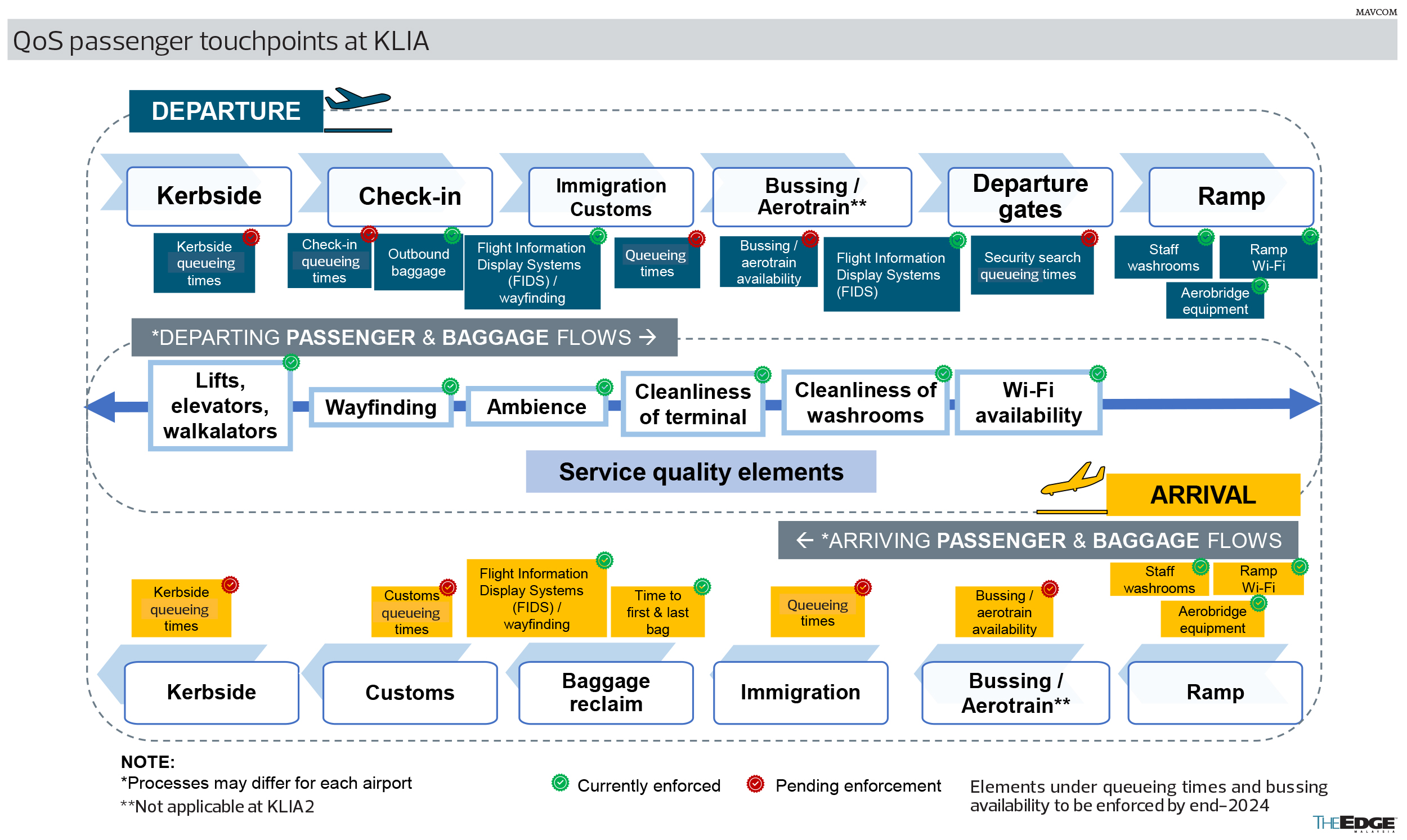

There are four main service quality categories in the scheme: passenger comfort and facilities, passenger and baggage flows, operator equipment and staff facilities, and queueing times. These four main categories will cut across all airports in Malaysia, but what service quality elements go into the QoS scheme would differ from airport to airport. Why? For instance, KLIA1 has an aerotrain system, but in Kuching Airport there isn’t. So this scheme is not one size fits all.

How does Mavcom monitor airports’ performance?

There are sensors installed by MAHB throughout KLIA, where the data is shared with Mavcom on a monthly basis. The only subjective measure that we have in the whole scheme is the passenger survey. The rest are all automated in the system. We employ an independent surveyor to carry out passenger surveys at airports. We also appoint independent inspectors to monitor the cleanliness of the toilets in KLIA1 and KLIA2.

The list of what needs to be checked is transparent to the airport operators so that there is no dispute with Mavcom. In fact, we give the airport operators a ‘shadow’ period of three months to six months to make sure that they get their systems in order before we enforce the service quality elements. We tell them these are the areas you should watch out for and that need improvements. The objective of this whole scheme is not to impose a penalty for non-compliance, but we want to drive efficiency. There is a directive that we sign between Mavcom and the airport operators where we can impose a non-compliance penalty based on these legal instruments.

But for smaller airports, we don’t need them to install sensors to monitor because not many people pass through these airports. So we need to balance the investment costs for MAHB as well.

There’s also the matter of resources. There are two sides of the coin as well. We hear airport operators saying they give, for example, 10 counters for airlines to check in their passengers, but the airlines only have six people manning the counters. So we want to go back [to the airlines] with data to say this is why your queues are long. This is where we have to be very careful. The revenue at risk here is everything that is under the umbrella of MAHB, but there are certain components within the ecosystem of the airport that do not belong to MAHB. For instance, the check-in, immigration, customs and quarantine. So we are going to publish these results on our website starting July this year. It is going to be a name and shame.

As for ground handlers, when they come for renewal of licences, we will look at all your failures of your performance. It will impact their renewal eventually.

Our objective is to drive efficiency. We don’t want to impose a fine on them. We give you a grace period for you to buck up. We worked this scheme with you in agreement.

What happens when the airport operators do not meet the set service levels?

Failure to achieve targets will result in a financial penalty of up to 5% of the airport operator’s aeronautical revenues (which include PSC, aircraft landing and parking charges, and net user fee payable to the government). How we spread the 5% will be across the four main service quality categories in the scheme. We have imposed a penalty of RM2.9 million for quality performance failures on MAHB to date. The financial penalty was for missed targets associated with cleanliness of washrooms, availability of ramp WiFi service, baggage not loaded onto the aircraft, and the delivery of baggage — time to first bag and time to last bag. For instance, an airport operator is only allowed to have four bags ‘short-shipped’ out of 10,000 bags. If short shipment occurs more than four times, then it is recognised as non-compliance.

The biggest challenge for us was [implementing the QoS scheme] in KLIA1 and KLIA2 because they are the biggest airports in Malaysia. We have a total of 28 service quality elements for both terminals, but we have enforced 20 so far. We expect to implement the remaining eight elements by the end of 2024, which will include bussing availability, and queueing times at kerbside, check-in counters, immigration, customs and security search.

In the absence of the aerotrain services at KLIA1, we are going to start monitoring their bussing services from May this year. We will measure two things — availability and punctuality. We are also compelling MAHB to make sure that they install sensors at the departure and arrival kerbside — to monitor how long cars stay there. We also plan to implement the service quality element for queueing times at the check-in counters this year. However, the engagement with the airlines hasn’t taken place yet.

Can you share some examples of how Mavcom measures the service quality elements introduced at the airports?

For toilet cleanliness, 90% of the time, your toilets must be clean. Then overall cleanliness, we look at the dissatisfaction score. We want to know how many per cent of users are dissatisfied.

As for baggage retrieval, the first bag at the main terminal building should arrive at the baggage belt [within] 20 minutes of the aircraft shutting down the engine whereas the last bag is within 40 minutes. For flights at the satellite terminal, the first bag should arrive at the baggage belt [within] 20 minutes of the aircraft shutting down the engine whereas the last bag is within 50 minutes. This is due to the distance between terminals and baggage belt, and flights from the satellite terminal have larger aircraft.

These service quality elements are not plucked from the air, but are based on a motion study that we did at the main terminal building and satellite terminal. Together with the airport operators, Mavcom, airlines and ground handlers were involved in the motion study. We also benchmark our timing against other international airports of similar size as KLIA as well.

Most of the service quality elements have a target of 85% to 99%. But you cannot compare apples to apples because you need to also include the infrastructure of KLIA.

But we recognise that airports also need to be competitive to get new airlines to come on board. In fact, these [service quality elements] are all their winning points.

And if I am an airport operator, I should be measuring these myself. I should be coming up with my own targets and service quality framework. Why do you need a regulator to do this? If you have strong airport operators running the airports, this should be part and parcel of their key performance indicators.

Transport Minister Anthony Loke recently commented on a survey that ranked KLIA as the eighth-worst airport in Asia, noting that rankings by surveys should not be considered as being conclusive as the methodology of the survey was unknown. Do you agree?

Yes. For instance, the body that is responsible for airports is ACI. So I would go for ACI’s survey results because they focus purely on airport experiences and they do airport service quality surveys. We have to be very careful with all these surveys that are coming in — what is their source, their data and who they are — that is very important. To me, what we should look out for are the results from ACI and IATA. [Airports and airlines should] go to a credible organisation that will provide an independent survey done by passengers, get an accurate sample size, and the measurements must be the same.

Does Mavcom monitor airlines’ service levels?

We have the Malaysian Aviation Consumer Protection Code (MACPC), which came into operation in July 2016 and was amended in 2019. This is another legal instrument which binds the airlines to comply with [it]. Airlines have been fined RM4.76 million by the aviation regulator for non-compliance of the code so far.

For the MACPC, do you know how many rounds of engagements with airlines we did? Obviously you won’t get to have everything agreed to by them, but sometimes we have to make an executive decision, but we are very careful of the executive decision that we make — whether it will benefit or are the airlines going to lose out financially. They don’t. And out of the 18 or 19 new regulations that are going in, the airlines come back and provide some justification for some of them and we pull out. For some, we said, ‘No, we are going to go ahead.’ And some we said, ‘Okay, we need more research to be done, we parked it to the next revision.’ To say that we are just fining them for a reason is not fair. We also have to present this to the transport minister. So we have to make sure that we have this right balancing act for the consumers as well as the industry.

The systemic issues that are happening in the industry will continue to happen, such as flight delays and cancellations. So we come up with regulations that meet 80% of that, and the remaining 20% we will manage.

All the international carriers will have their own set of value propositions when things fail. Our biggest issue is domestic. Singapore doesn’t have a domestic market. It is not an apple to apple comparison. We have a huge domestic market. But I know that other Asean countries that have the same problems with domestic markets like Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines are looking at Malaysia as a benchmark. They want to introduce a similar QoS scheme in their countries.

What happens after the merger between Mavcom and the Civil Aviation Authority of Malaysia into a single aviation regulatory agency?

With the merged entity, the work [to monitor airport and airline services] will continue. These are the same standards that will be expected. We have no control of what’s happening beyond what is going to happen but right now, we have control on what we can do at this stage as long as we have Mavcom. Not easy when an organisation goes through this transition, a lot of emotions also happen within. We are also human. But we want to remain focused and committed to make sure what we can do for the consumers. I always tell my team if we cannot control something, be honest, let’s not think about it. Let’s do what we can under the Malaysian Aviation Commission Act 2015 and we make sure that we execute what we can.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.