This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 11, 2023 - December 17, 2023

GAMUDA Bhd has been riding the government’s infrastructure spending for decades now, benefiting from investments such as the SMART tunnel and Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) projects. Lately, however, the group has been exploring and winning more contracts overseas than at home.

In fact, Gamuda may have to look for more contracts abroad as the roll-out of catalytic infrastructure projects that would benefit both the group and the construction sector faces delays, owing ostensibly to the government’s fiscal position.

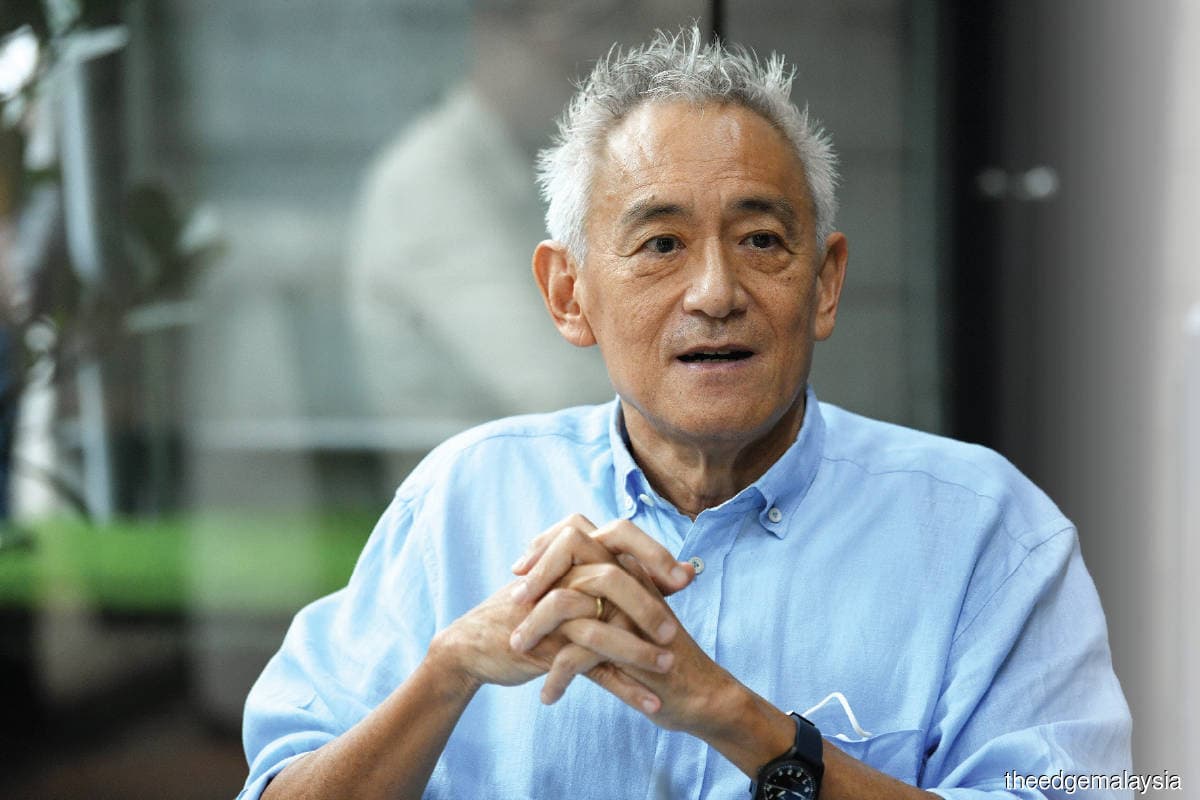

In an interview with the media at Menara Gamuda last Thursday, Gamuda group managing director Datuk Lin Yun Ling says: “[It would be good] if the current government could find a way out of this [subsidy issue that is taking up too much of the budget]. I mean, to be fair to them, I don’t think they created it. It was inherited. But if you can’t get out of this vicious cycle, we all know, every one of us here knows, how much do you have left?

“If you spend RM80 billion and next year it will be RM90 billion, the year after that will be RM100 billion a year on subsidies. How much do you have left for other things? Now, not much for infrastructure; a few years down the road, even not much for education. Healthcare is already struggling.

“So, if you ask me, will it be worse in the coming years? Can the government reduce this RM80 billion a year? So, everything is blocked.”

In 2022, the government spent RM80 billion in total on subsidies.

As at October 2023, Gamuda had an outstanding order book of RM24 billion, with work in Malaysia constituting 24%, or RM5.7 billion, of the total. Australia has become the largest market for Gamuda’s engineering and construction segment, with an order book of RM12.1 billion.

Successive Malaysian governments have had to raise debt levels to pay for development expenditure every year, as almost all of its revenue went towards operating expenditure. Opex as a percentage of government revenue has averaged 99% over the last 10 years and has not fallen below 90% since 2007. Subsidies and social assistance made up as high as 22.9% of revenue in 2022 and are expected to remain high at 17.2% of revenue in 2024.

The Madani government under Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, which came into power in November 2022, had pledged not to breach the statutory debt limit of 65% of gross domestic product (GDP). Without meaningful fiscal reforms, however, major infrastructure projects might continue to be put on hold.

To be fair to the government, it is working towards rationalising subsidies, with the Ministry of Economy developing the PADU central database to ensure that only the needy receive subsidies, especially fuel subsidies. Lin questions, however, the government’s political will to push through with the subsidy rationalisation.

“You can talk about the plans, but will [the government] do it? How much of it will they really do? I’m sure you see at the end of the day, once subsidies become more targeted or reduced, you will have higher inflation,” he says.

“The reality is the objective of politicians is to win the next election and to survive. Is there anyone we know who would say, ‘I don’t care whether I win the next election; I will do what is right for my country’? Let’s see.”

The practice of subsidising essential items from fuel to toll roads has an unintended consequence of suppressing wages, as companies observe the Consumer Price Index every year before they decide on wage increments, says Lin.

Although the CPI is not the only determinant of wage increases, it is one of the factors that they consider, Lin observes. And as Malaysia’s CPI has remained artificially low for decades, as prices were suppressed by subsidies, wages too have been stagnant.

Gamuda has been venturing abroad for years and now has a presence in Taiwan, Singapore, Vietnam and Australia. Over the years, Lin has had a front-row seat to watch the economic development of these countries compared with Malaysia’s.

He says that over the last 20 years, the average salary of engineers in Vietnam has surpassed that of their Malaysian counterparts, although the latter was higher in the first place. This is because salaries in Malaysia have not grown as much as in Vietnam over the past two decades.

“For me, that is the effect of subsidies. I’m not saying subsidies equal price control, [but] subsidies have a lot of effect on prices. And if you look at the CPI basket, most of the items are all price-controlled,” says Lin.

He adds that if the government re-targets subsidies, the private sector will have to pay its workforce more to make up for the higher cost of living that comes with it. This will then result in higher purchasing power in the market, which could attract the private sector to invest.

Lin laments that the low income levels of Malaysians have made the country less attractive to private investments, even if the government wants the private sector to drive the economy and invest in infrastructure.

“Even if the private sector wants to invest in new toll highway projects, they find the government’s approved revenue or toll rate so low. How do I get a decent return? So, you can see how it affects the investments.

“A lot of foreign investors are not looking at infrastructure. I have seen over the recent months that many economists have spoken about this. When you have price controls, it affects your investment prospects. Without investments, it affects your growth.

“It is just one aspect of this vicious cycle, but can the government remove the price controls or the subsidies? Can they force wages [up through the removal of subsidies]? There’s a disconnect between the political will and what we call common sense and reality,” remarks Lin.

Overseas move not driven by thin margins but by opportunities

Gamuda is among the handful of Malaysian construction groups that have been making headway overseas. On Dec 6, the group announced that the Land Transport Authority of Singapore had awarded its Singaporean branch a S$509.57 million (RM1.78 billion) design and construction contract for the West Coast station and tunnel.

This latest project marks its first independent venture in Singapore without joint-venture (JV) partners, showcasing the group’s strong delivery track record in the region and solidifying its role as a key player in the city state’s transport infrastructure development.

Commenting on this achievement and whether Gamuda will continue to bid and secure more construction contracts overseas without local partners or a consortium, Lin says the challenges and acceptance of the players and authorities vary from market to market.

“You take a long-term approach [when it comes to going overseas] but, of course, not to our surprise, Singapore will probably be the first one where the government of the clients knows you well enough. After two or three jobs, they ask, why do you need a local partner?

“Are we there yet in Australia? For many projects there — maybe not for a few very big ones, because even the locals are required to partner each other — the clients are very risk-averse,” says Lin.

He adds that highly risk-averse clients are the reason contracts in Australia generally come with lower margins compared with contracts in other markets. In Australia, while the top-level margins could be between 8% and 10%, the overheads are high.

In Malaysia, he says, consultancy costs on average take up 2% of project costs. In Australia, it could be up to 7%, but in Taiwan these days, contracts have good margins.

“In Australia, it is a very compliant and risk-averse culture. For everything, the client will want you to have consultants to [check, audit and certify].”

In the first quarter ended Oct 31, 2023, Gamuda made RM2.14 billion in revenue from its overseas businesses (both construction and property), but only RM136 million in net profit for a net profit margin of 6.4%.

Meanwhile, its Malaysian businesses brought home RM709.9 million in revenue in the quarter, and RM59 million in net profit for a net profit margin of 8.3%.

Despite the thin margins, Lin stresses that the move overseas will continue for Gamuda, as it is about the future of the group, rather than chasing margins.

“If you look for the right margins, probably it does [re-allocate capital to higher-margin markets]. [You can’t just say,] ‘Oh, I just want to be in Taiwan’ or ‘I just want to be in Malaysia’. You have to look at what the future is like; how many infra projects can the government afford to do?

“We think there are many opportunities for growth in Australia, for example. We know the risk is that your overheads are going to kill you. You have to find a way to make it work and be more cost-efficient,” says Lin.

Gamuda has certainly grown in its overseas markets. In Taiwan, for example, the group clinched the tunnelling contract for the Kaohsiung MRT Orange Line in 2002 with its 50:50 JV partner New Asia Construction & Development Corp.

Then, in 2022, in a 60:40 JV with Asia World Engineering & Construction (AWEC), Gamuda was awarded a US$451 million contract to build a new underground alignment and commuter station in Pingzhen District, in Taoyuan City.

In October, the latest, unincorporated JV between Gamuda and AWEC was again awarded a 4.4km railway track contract in Niao Song District in Kaohsiung. This time, the Malaysian outfit will take 88% of the job and be the lead contractor.

Meanwhile, in Malaysia, Gamuda is diversifying into renewable energy projects. Apart from its 30% investment in solar energy service provider ERS Energy Sdn Bhd, Gamuda has also secured the development of a hydroelectric power plant in Upper Padas, Tenom, Sabah.

The RM4 billion project saw Gamuda taking a 45% stake in a partnership — called UPP Holdings Sdn Bhd — with Sabah Energy Corp Sdn Bhd (SEC) and Kerjaya Kagum Hitech JV Sdn Bhd (KKHJV). According to Gamuda, the project will anchor a new recurring income division for the group.

Given that the Upper Padas hydroelectric power plant project is a public-private partnership, questions arise as to whether companies such as Gamuda can undertake more private funding projects for other types of infrastructure projects, in view of the government’s tight fiscal position.

“It doesn’t work for every project because for some of these infra projects, even in other countries, the revenue will not be able to fund your capital expenditure. You are lucky if you can pay the interest on your borrowings [for the project],” says Lin.

All this goes back to his argument that once wages become low, many of the infrastructure projects are no longer financially viable for the private sector to invest in.

“It is not just train fares. Your water tariffs are low, and Selangor hasn’t increased tariffs for the last 18 to 20 years,” Lin says. “That means it has become cheaper. If the government doesn’t get to increase electricity tariffs … then all this will spill over once you have that subsidy culture and nothing is priced to market.”

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.