This article first appeared in Forum, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on March 27, 2023 - April 2, 2023

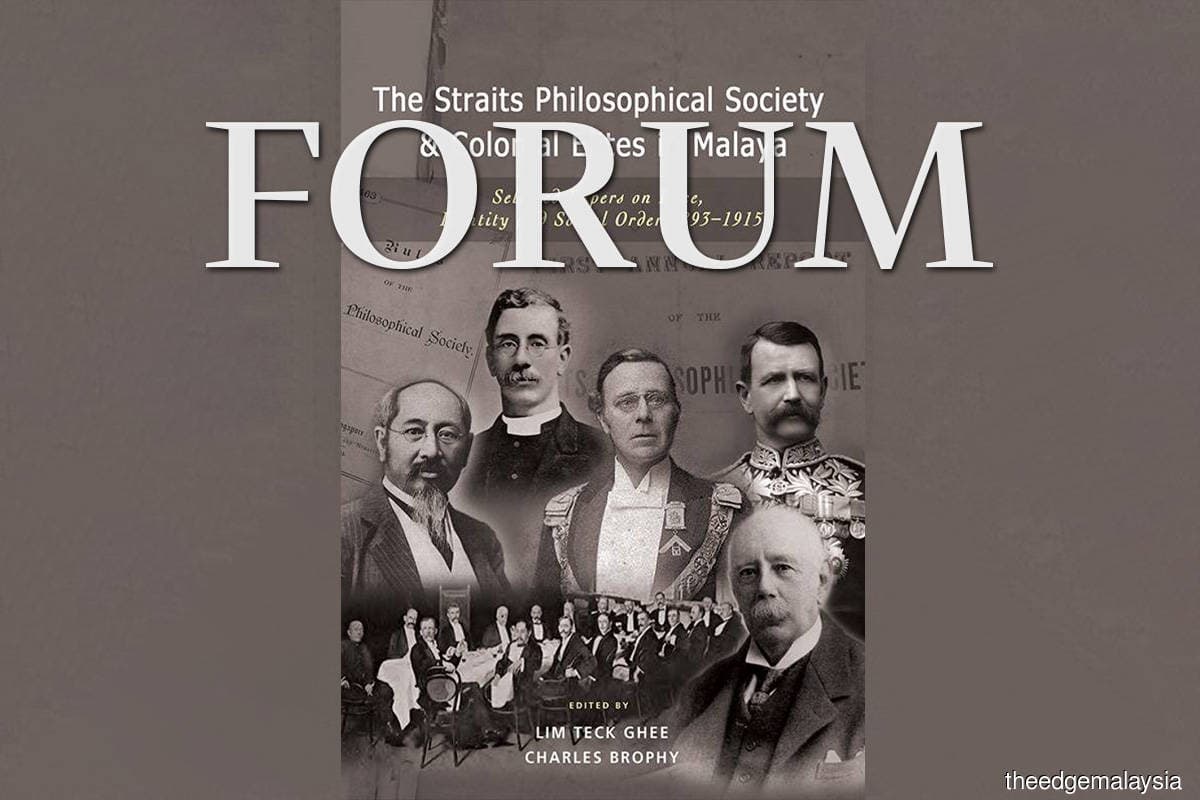

A review of Lim Teck Ghee and Charles Brophy’s The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya (ISEAS, 2023)

Introduction

Almost a decade ago, I was made aware of this work on colonial history by one of Asia’s most prolific social scientists, Lim Teck Ghee, who conceived it as a commentary of essays. Today, after almost 50 years, the much-awaited collection of the writings of the colonial elites of The Straits Philosophical Society has come to elegant fruition. The volume is admirable in that work on it began with Lim’s 1976 discovery of a set of “about to be discarded” unpublished philosophical papers in the Penang state library and how he salvaged this valuable set of 17 papers.

The result is a collaborative effort with a prolific UK-based editor and scholar of colonial history, Charles Brophy, to produce this volume of commentary on the primary sources of the work of The Straits Philosophical Society.

This publication is timely, especially for today’s academics and students of Southeast Asian history interested in understanding the philosophical debates that were happening in late 19th-century Singapore and Malaya.

This 462-page book, consisting of 30 essays, should be a delight to those interested in political philosophy as it pertains to British colonial history. It offers us a glimpse of the value of philosophical thinking in developing perspectives on the inner workings of colonialism, offering a range of critical themes — from the basis of colonial ideology, the psychology and political economy of the Straits Chinese, the impact of the Opium Wars on the Chinese in Malaya, to the extensive narratives on the colonial construction of Malayness.

This review concerns not only the educational value of the work of the Society today but also the debates on how the colonies should be governed for maximum return, taking into consideration race, religion and ethnicity of the colonised.

Core argument

This quote exemplifies the essence of the work, the transcultural flow of ideas at the time of early de-colonisation: “ ... Nevertheless, beyond the model of the philosophical society the Society represented, the ideas propounded in the Society can also be said to have had far-reaching consequences beyond its life. The mixture of ideas around liberalism, Darwinism, colonial modernity and race, constituted the basis for a dominant ideology in colonial Malaya, centred on the necessity of European modernisation, a critique of liberal ideas of empire, the protection of native races, and the racial distinction between Europeans and Asians.

“Yet as the Society also evidenced, this schema also contained its own tensions — tensions which were played out in the presentations and critiques of the Society. More importantly, in opening a space for non-Europeans to engage with colonial thought, the Society also made possible its appropriation and modification and, as in other colonial learned societies, contributed towards the development of an independent intellectual culture in British Malaya, developing around ideas of nationalism and national modernity. This engaged not only with transnational flows of nationalist and modernist thought in the colonial world but also formed the basis for early nationalist thought and development in the Malayan Peninsula.” (Lim and Brophy, 2023)

Looking at The Straits Philosophical Society from the perspective of critique of ideology, we discern these contending ideas of society and how they evolve through political will and practices of the “strong state”, (based on a command economy and authoritarianism). Evident is a dialectic tension of the march of the history of ideas. What revolutionary leaders or political elites learnt from the former colonies is not merely how to continue to subjugate the coloniser/natives through realpolitik but more long-lasting is the process of being educated on the contradictions of colonial rule.

Exemplary, in this fine collection are the contributions of colonial elites such as HN Ridley, William J Napier, David J Galloway, Tan Teck Soon, WR Collyer, Gilbert E Brooke and WG Shellabear, among other Straits philosophical luminaries, on the colonial project, on the Malay race and the Malay identity respectively, as they pertain to how to manage and advance the Malays and the interest of the British empire.

What is fascinating about this collection is not only topics such as the debates on how to govern the colony and the Chinese Straits community, especially in Singapore, within the context of the Opium Wars, gang membership and the way they are governed, but also the tedious and numerous discussions on the nature of the Malays, their religion and how the “people of the land” (today called the orang asal or bumiputera) responded to the advent and subsequently the subjugation of the British colonials.

The debates are epistemological and anthropological in nature, focusing on how the colonisers ought to understand whom they are colonising, especially when the latter had already an established system of kerajaan for those being governed, one based on the primacy of the “mandate of heaven of the Malay rulers”.

Contrasting world views on managing the colonies

As I read the essays and the intellectual construction and representation of the colonies and the colonised, particularly of the identity of the Malays, for example, I asked: “Where were the Malay scholars while these debates were happening? Why was there no one from any of the Malay royal court households when the fate of Malaya and the construction of the identity of the Malays were discussed?”

I had a hypothesis, presented here: The Malay rulers were not equipped, or rather, failed to equip themselves, with that vast array and arsenal of intellectual heritage. The evolution of literacy, technology and ideology did not favour the Malay world. What they had, even from the time of the Melaka kingdom is the loose concept of “daulat” and “kerajaan” as tools to glue enclaves and pockets of society in some form of concentric-styled loose entity of social control.

Discarding philosophy in Malaysian academia

Earlier, I mentioned the genesis of this project by Lim, of how these philosophical papers were about to be discarded by the state library. I find this metaphoric of the state of affairs of especially Malaysian academia today: the death of philosophy and critical sensibility after being discarded by the post-Tunku Abdul Rahman decades of Malay-Muslim hegemony and the constant attack on the word “liberalism” and, consequently, any attempt to bring about the teaching of liberal philosophies in the classrooms and into the minds of the students who have been fed by the ideologies of “Mahathirism”, an admixture of half-baked understanding of free enterprise and Malay nationalism whose state is governed via Soekarno-inspired “guided democracy”. As in the metaphor of the “butterfly effect of things” in history, in which events and consequences follow the pattern of chaos, order and randomness, so is the metaphor of the discarding of these philosophical papers that today signifies this nation’s failure to develop a thinking citizenry.

How to read this book

The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya is a work on philosophical ideas on colonial rule in British Malaya, a fascinating read if one is interested in philosophy in general and political philosophy in particular. Established at the end of the 1800s, the Straits Philosophical Society was a forum to intellectualise the directions and inner workings of the empire, especially on issues of race, identity and the economy. Pedagogically though, how do we read this collection of essays and commentaries then, if we are to use it to teach colonial history?

In my decades of teaching courses in the social sciences, I use primary sources as main texts to analyse phenomena and patterns in history. I would ask students to read first-hand accounts, treatises, letters and journal entries, and analyse visual text such as photos and other forms of narratives. Although students might have difficulty reading works such as those written in “archaic English”, they will be encouraged to persevere. I would guide them through the language usage and, most importantly, the content.

I suggest the essays be read as follows: First, read the primary essays; next, read the counter-arguments; and lastly, read what the authors/compilers have to say.

Conclusion

Lim and Brophy’s must-read work, in commenting on the primary sources of political philosophical ideas pertaining to race, identity and governing the Malay colony, is both valuable as an analysis and a classroom text to teach about colonialism and the construction of colonial identity. It is an elegant work in its own class of originality given the fact that these papers were about to be discarded.

The value of the collection of excellent essays lies in its nature as a primary source, which historians and teachers, especially of colonial history, would appreciate using in class. Even more valuable is the nature of philosophical arguments crafted and debated in the style of Marxist dialectics concerning how the colonies, especially Malaya, are to be governed.

The ideologues in the essays have differing conceptions of human nature, the interpretation of world views, race and identity, Malayness, and how human labour in the colonies is to be managed.

Dr Azly Rahman is an international columnist, academic and author of 10 books and more than 450 essays on Malaysian and global politics, culture and society. He teaches world history, global issues, psychology and sociology of the future in the US. He writes at Across Genres (https://azlyrahman.substack.com).

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.