ISSUES of housing supply, affordability, and home ownership have been in focus of late.

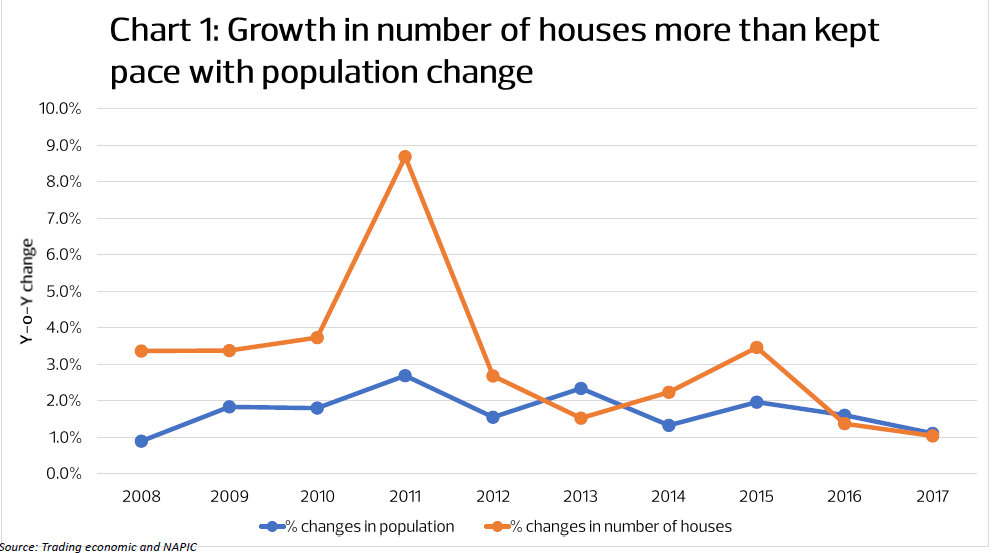

In a special report, The Edge examines the issue in detail. Statistics suggest there are enough houses built, with property developers churning them out at a rate that more than keeps pace with population growth.

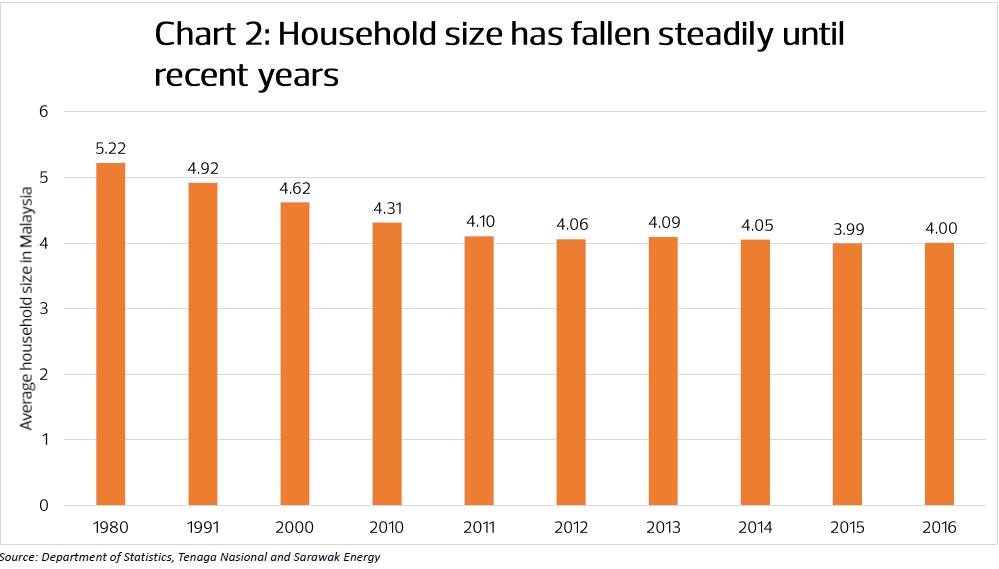

Over the last few decades, the average household size (persons per household) has declined from 5.22 in 1980 to just around 4 presently, underpinned by rising population, income levels and urbanisation.

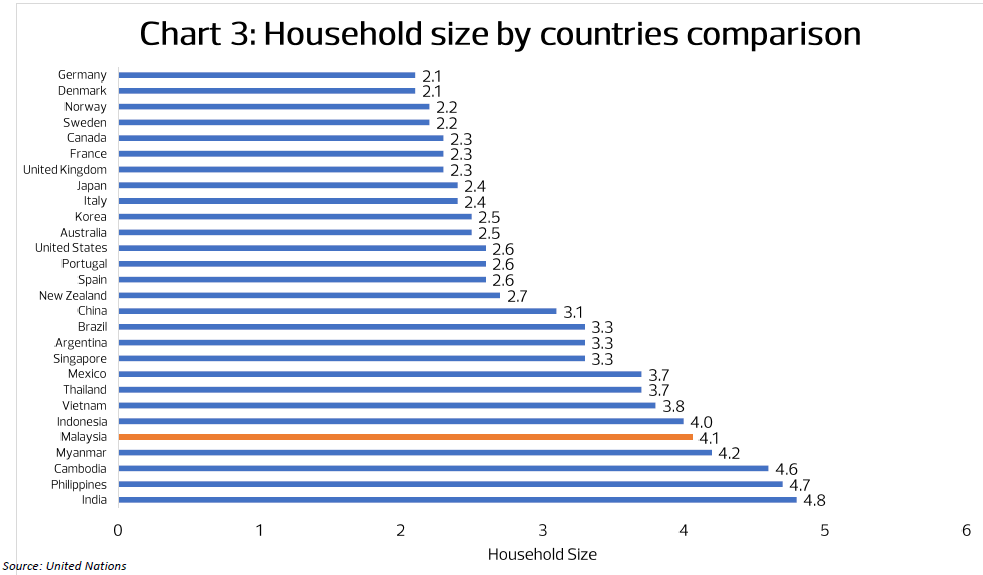

But household size has plateaued recently and is now comparable to neighbouring Asian countries in similar stage of economic development.

It is therefore unlikely that this figure will drop substantially from hereon, at least not for the foreseeable future. China’s small household size, is an outlier with it’s family planning (one child) policy, which it relaxed in recent years to include the possibility of two children if certain conditions are met.

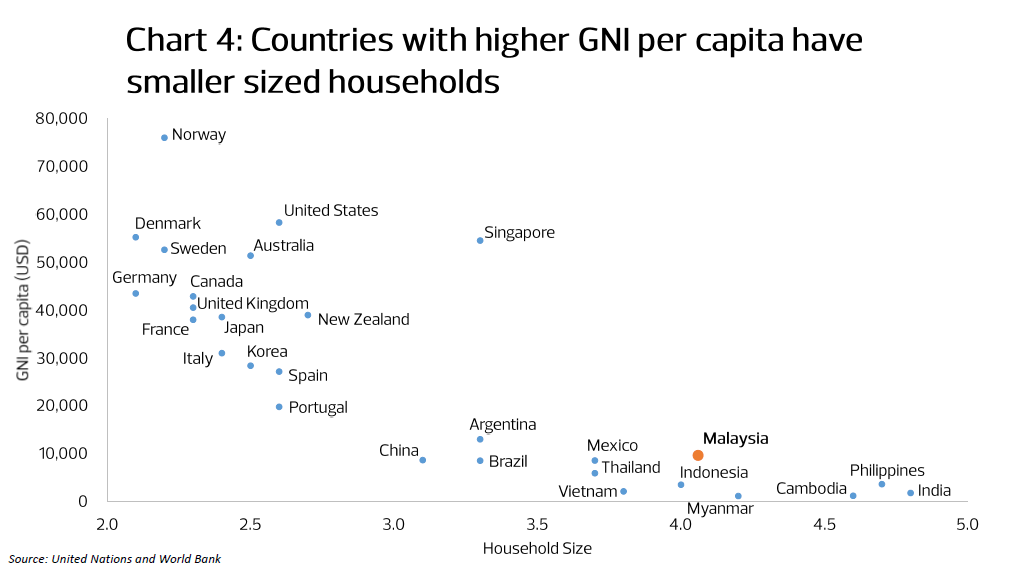

Countries with smaller household size (<3 persons per household) are mostly developed nations. Factors include demographics (aging versus young population), culture (there would be more multi-generational families under one roof in Asia) and crucially, income levels. Countries with higher GNI per capita have lower household sizes.

The population growth in Malaysia is slowing, the previous compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) was 2.64% in 1980-1991, and 2.17% in 2000-2010. The annual population growth is forecasted to slow further, from 1.8% in 2010 to 0.8% in 2040.

This population plateau means the urgency for more houses will abate, and the average household size in Malaysia could fall even further in the long run, as we move towards a high-income country status.

Unsold properties, their numbers mounting, is a telling sign that there is no shortage of houses to meet existing demand.

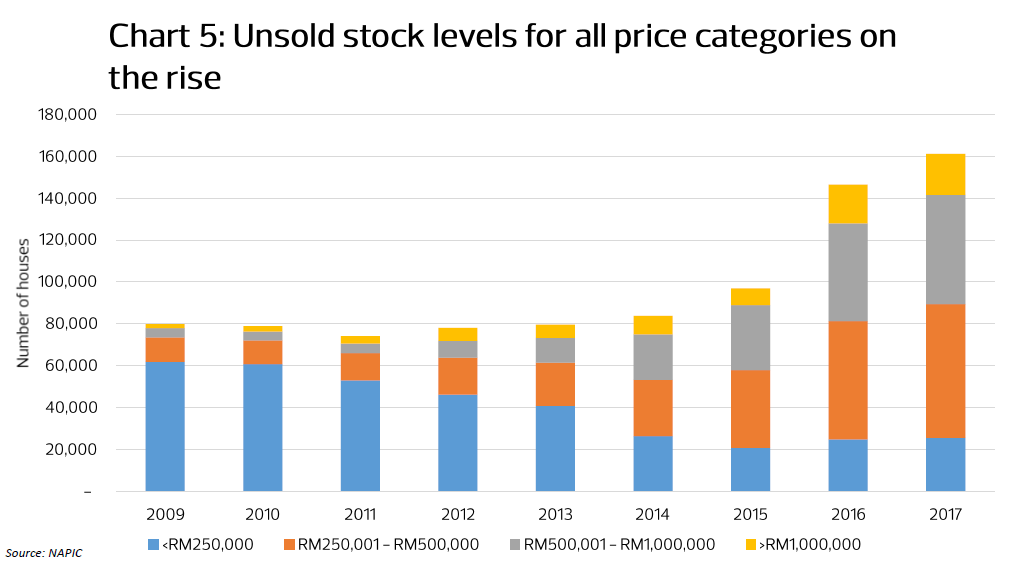

Unsold residential property numbers have been on the rise since 2011, spiking in 2016-2017 according to statistics from the National Property Information Centre (NAPIC).

This holds true across all price categories, including houses below RM250,000, which turned higher in 2016 and 2017 after having fallen for six straight years since 2009. Rising unsold stock is especially evident for houses priced between RM250,000-RM500,000 and RM500,000-RM1 million – likely exacerbated by the March 2014 restriction on foreign buyers.

Clearly, Malaysia does not need to build more houses in the near to medium term. Affordable housing or otherwise, the demand isn’t there, while the unsold supply languishes, unwanted.

Yet, talk of people wanting to buy houses, but not being able to do so abounds. Which means, demand does exist, but the issue is affordability.

Young adults, a growing segment of the market, want to buy a home but cannot afford to on their incomes.

The two common ways to solve this issue, are to build more affordable homes, and loosen lending regulations to make more loans available.

But these are not sustainable solutions.

The competitive property sector has no real barriers to entry, and is market driven. Developers compete to sell their properties, on price, location, facilities and amenities. So, if house prices could be lowered to meet demand, at the right quality and location, it would have happened.

In fact, this is already evident.

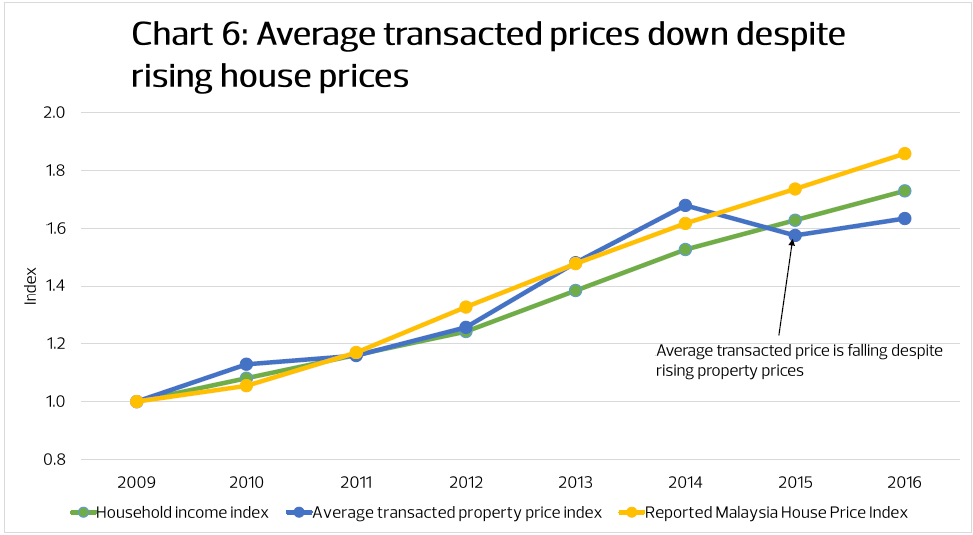

The average transacted house price has fallen in recent years.

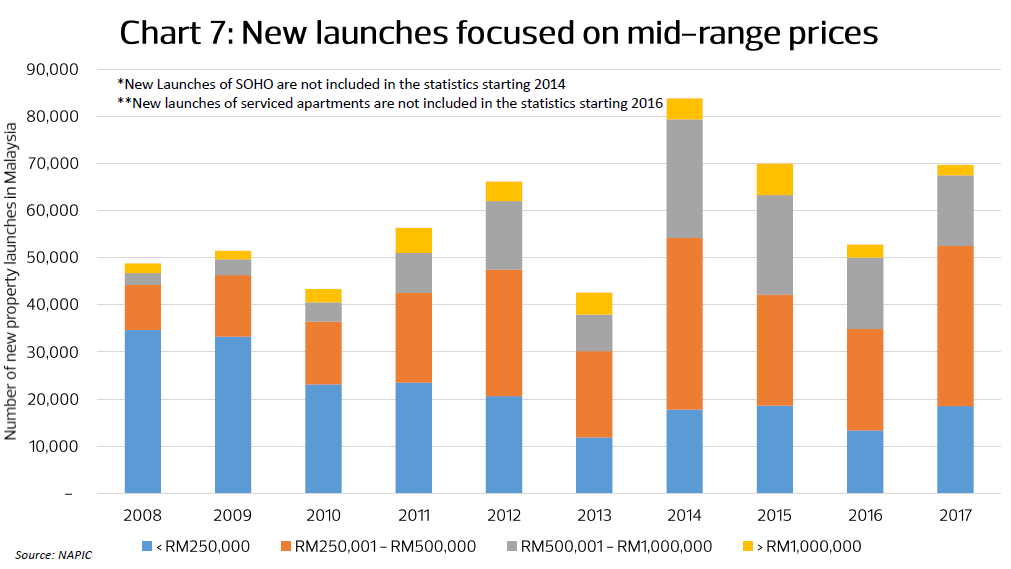

Developers have already responded to prevailing market situation by building cheaper houses.

The majority of new launches feature houses under the RM1 million price tag, particularly those between RM250,000 and RM500,000. For the lower price range, new launches are mostly between RM150,000 and RM250,000.

However houses priced under RM150,000 are few and far in between, due to financial feasibility.

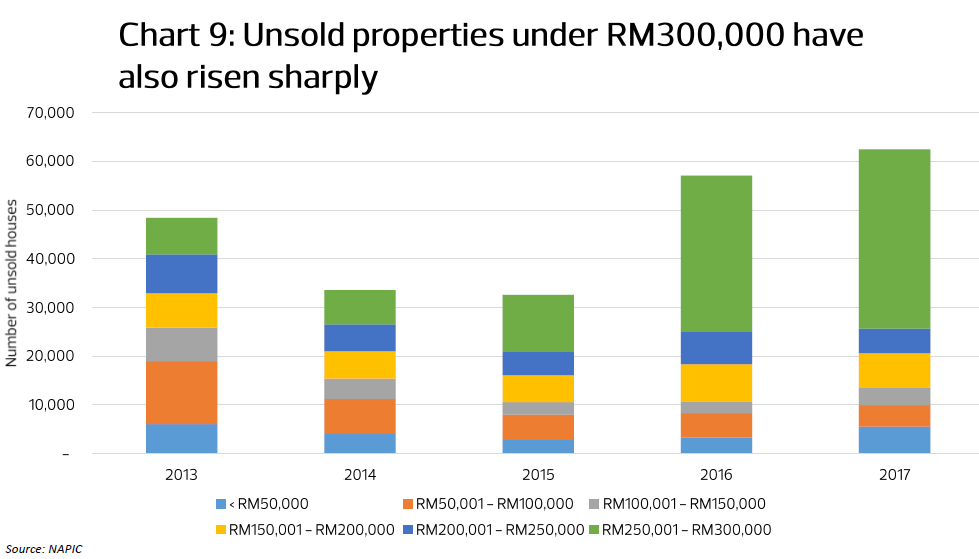

Houses that are priced under RM300,000 also remain unsold, and the numbers of unsold properties in this price range have risen.

For quality housing that includes good facilities, at a minimum of 850 square feet in reasonable locations with connectivity, parks and shops, it is unlikely to see prices below RM280,000 in the Klang Valley.

Construction costs can account for just under half of the price, land cost is roughly 15%, finance, legal, utilities and architecture costs and the like comprise another 13%, then 24% goes to sales and marketing, and finally, gross profits.

In an effort to lower prices, smaller and smaller sized houses and apartments are being built, but there is a limit.

To lower the price further, it must come with some caveats. Far-off locations, lack of quality, compromising on connectivity, infrastructure, amenities and facilities. Affordable, but undesirable.

Thus, if efforts in lowering the cost of houses isn’t working, then the next solution is to loosen financing and allow people to borrow more or lengthen their mortgages.

Banks are commercial entities who will lend to anyone deemed to be creditworthy. Lowering credit requirements would be irresponsible and risky, with the chance of systemic risks down the road.

Defaults and foreclosures may result, and in turn, impact the banking system and the country’s economy negatively.

Lengthening the repayment period of mortgage would help — but a 45-year mortgage basically means one has to bear the debt burden beyond retirement age of 60, assuming you start working at age of 21.

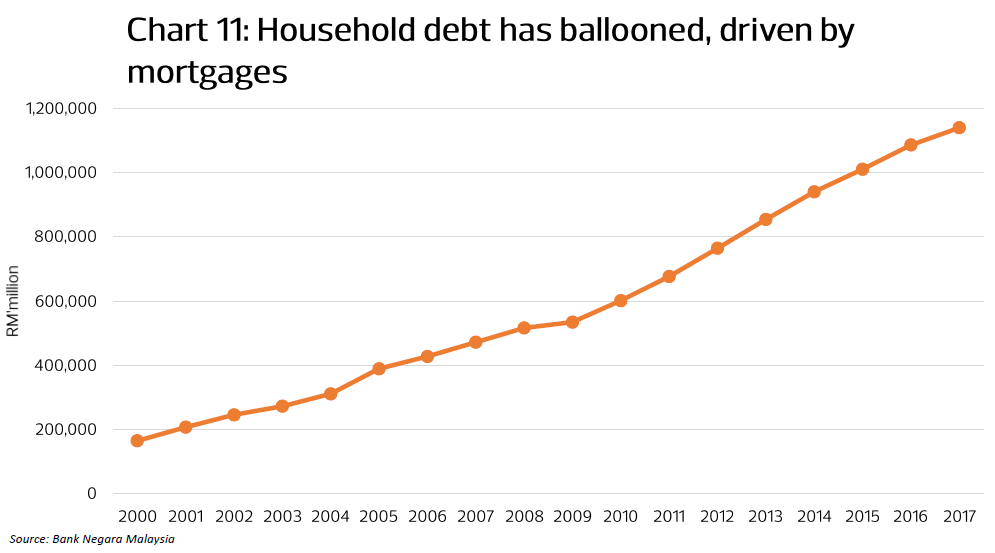

The average Malaysian household is currently amongst the most indebted in this region — and has limited room for additional leverage.

So how now? Rent instead of buying a home? But renting does not build equity. Neither does it help improve the prospect of homeownership in the long run.

What we need is an innovative solution that hasn’t been proposed just yet.