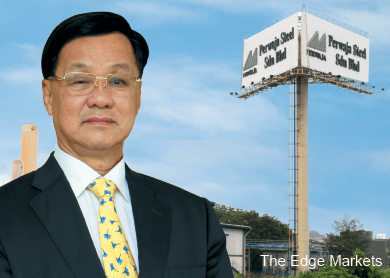

WHEN Kinsteel Bhd acquired a 51% stake in Perwaja Steel Sdn Bhd some nine years ago, Tan Sri Pheng Yin Huah was touted as an emerging steel magnate who could help the latter company scale the heights of the industry. Today, battered by depressed steel prices, high energy costs and Perwaja’s mountain of debt, it is the Pahang businessman who needs to call for help.

With zero cash, accumulated losses of RM1.89 billion and debts of RM2.22 billion, Perwaja has seen its market value shrink to only RM44.8 million from RM722.4 million in December 2009.

The market value of Kinsteel (fundamental: 0; valuation: 1.2), Pheng’s first listed company, has tumbled to RM131.2 million from RM842.6 million, thereby seeing his family’s 29.96% stake in the steel outfit now worth RM39.3 million compared with RM320.8 million in 2009.

Desperate for a rescue, Kinsteel and Perwaja (fundamental: 0; valuation: 0.3) have approached Chinese investors for fresh capital infusion of hundreds of millions of ringgit. But this means the Pheng family’s holding in Kinsteel could be substantially diluted while Kinsteel’s 31.25% stake in Perwaja will almost certainly be flushed out as the latter will end up issuing a large number of shares to the Chinese investor.

In an interview with The Edge, Pheng, now 66, is apologetic to Tan Sri Abu Sahid Mohamed — his partner in the beleaguered Perwaja — about how things have turned out at the steelmaker. But he insists that he has never regretted Kinsteel acquiring the controlling stake in Perwaja from the well-connected businessman in 2006.

“It’s not just about me making a wrong choice. It’s more of the challenging business environment and the problems in the industry. I don’t see this as a bad investment and I have no regrets at all. We learn from our mistakes, that’s part of living,” he says, adding that looking back, he would have still taken a bold bet on Perwaja.

Pheng is still the managing director of Kinsteel, although he relinquished his executive role in Perwaja in December last year after being re-designated a non-executive director.

This is the first time the Kuantan-based businessman is talking about Perwaja since its plant in Kemaman was forced to close in August 2013 after its energy supply was cut. This happened after the company repeatedly missed its bill payments to Tenaga Nasional Bhd and Petroliam Nasional Bhd.

Feeling bad about the closure of the plant, which employed 2,000 workers, Pheng is hoping that China-based alloy manufacturer Zhiyuan Investment Group Co Ltd can help revive Perwaja’s fortunes by turning it into a manufacturer of higher-margin stainless steel products.

When asked about his future role in Perwaja when the Chinese investor comes in, Pheng says he intends to stay on in the company and Kinsteel, as much as he hopes to maintain the listing status of the two companies.

“One thing is for sure, we (Kinsteel) will stay on in Perwaja. But it doesn’t really matter who will eventually control Perwaja. For us, it is more important to bring in a new investor who can revive the Kemaman plant.”

No regrets

Talking over lunch in Maju Junction Mall in Kuala Lumpur, Pheng sounds troubled when the conversation steers towards Abu Sahid, although Perwaja’s failure has wiped out the bulk of his family’s wealth too.

“To be fair to Abu Sahid, he gave us a free hand in managing Perwaja. Now that we have let him down, of course, we feel sorry for him. But the downfall was due to many other factors too, not just a management problem,” he says, adding that Kinsteel has also invested heavily in Perwaja, which makes it equally painful for him.

Maju Junction Mall is owned by Abu Sahid’s Maju Holdings and it is where his headquarters are.

Industry talk had it that the problems at Perwaja had soured relations between Abu Sahid and Pheng. Steel industry executives say Pheng was spending most of his time attending to the affairs of the Federation of Chinese Associations Malaysia (Hua Zong), leaving the day-to-day running of Perwaja to his son Datuk Henry Pheng.

It was a challenging task for Henry, who was more used to the downstream operation at Kinsteel than the complicated upstream operation at Perwaja, says industry observers.

Some say Pheng won the coveted position of president of the influential Hua Zong in 2009 largely because he became prominent after the Perwaja takeover. Overnight, the Chinese community started comparing him with long-time steel magnate Tan Sri William Cheng, who is also active in the Chinese association circles.

When met for lunch recently at his home, Abu Sahid denies having a strained relationship with Pheng.

Having sold 51% of Perwaja to Kinsteel in 2006, Abu Sahid today still retains a 31.91% direct stake in Perwaja and a 16.09% stake in Kinsteel. When Perwaja went for listing in 2008, both Kinsteel and Maju Holdings sold some shares.

It was Abu Sahid who had chosen Pheng to be his strategic partner in Perwaja to grow the steelmaker after it started making profit. This was 10 years after Abu Sahid had taken over the then scandal-wrecked and debt-laden Perwaja from the government in 1996, briefly after there was a vacuum in its management with the resignation of the late Tan Sri Eric Chia.

It was reported that in 2006, Cheng’s Lion Group had offered Abu Sahid three times more than the RM298 million Kinsteel paid for the 51% stake in Perwaja and another steel plant in Gurun.

Not just Cheng but also banking tycoon Tan Sri Quek Leng Chan and British Indian steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal had expressed interest in the steelmaker at the time. The price Kinsteel paid for the Perwaja stake was deemed a steal, considering that Abu Sahid’s total cost of investment in the latter was RM713 million at the time, according to a filing with Bursa Malaysia.

In the end, Kinsteel was chosen to helm Perwaja as Abu Sahid believed Pheng and his three sons could work with him to turn the company around. The stake sale left Maju Holdings with 49% in Perwaja until its listing in 2008.

Indeed, Perwaja was profitable in 2006, 2007 and 2008, when the global economy was booming with commodity prices rallying strongly due to surging demand from China.

However, towards the end of 2008, the US subprime mortgage crisis erupted and the global economy went into a tailspin. This saw the demand for steel and its prices come crashing down. In the following years, while the global economy, especially China, recovered, Perwaja was hit by the high cost of gas and electricity amid the gradual removal of subsidies. Dumping by Chinese steel mills in the domestic market only made matters worse.

The steelmaker soon ran out of cash and its Kemaman plant was shut down. This was more than 20 months ago.

Despite equity losses of hundreds of millions of ringgit, the business partners say they have no regrets about having teamed up.

“I have never regretted the decisions I have made. In fact, there is no regret in the business world. We just have to move on, that’s life. You win some, you lose some,” Abu Sahid says ruefully.

Pheng insists that he still has a good relationship with Abu Sahid as no one should be blamed for Perwaja’s failure. As an entrepreneur, he says, he was not pampered on his journey. “If you have a chance to expand, you have got to make a choice. You shouldn’t stay in your comfort zone. I see this as a learning process. It has trained us and opened our eyes.”

How it started

A shortage of steel in the country prompted the government to set up an integrated steel mill in 1982.

Back then, Perwaja was a joint venture between Heavy Industries Corp of Malaysia, the Terengganu government and Japanese firm Nippon Steel Corp.

In 1988, the government brought in Eric Chia to assume the role of Perwaja managing director. Despite various restructuring efforts, Perwaja continued to be in the red and ended up accumulating losses of about RM2.5 billion in the financial year ended March 31, 1995.

Maju Holdings came into the picture in 1996 when it submitted a proposal to privatise Perwaja. While Abu Sahid began assuming management control of Perwaja, the privatisation plan had to be put on hold due to the Asian financial crisis, before it was revived in 2000 and completed in 2003 with Maju Holdings as the ultimate holding company.

Then in 2006, Kinsteel bought from Maju Holdings a 51% stake in Perwaja and 51% of its plant in Gurun, Kedah, through Perfect Channel Sdn Bhd (its 51%-owned subsidiary) for a combined value of RM297.6 million. Subsequently, Perwaja went public at an IPO price of RM2.90 per share on Aug 20, 2008, which coincided with Abu Sahid’s birthday.

According to Bloomberg, the market capitalisation of Kinsteel and Perwaja was RM842.6 million and RM722.4 million respectively in December 2009 (see table on Page 59). Now, with their shares trading at around 12.5 sen and eight sen respectively, their market value is down to RM131.2 million and RM44.8 million.

The Pheng family’s wealth in Kinsteel has shrunk from RM320.8 million to RM39.3 million while the value of Kinsteel’s stake in Perwaja can even be described as wiped out — from RM270 million to RM14 million.

Meanwhile, the value of Abu Sahid’s stake in Perwaja has declined from RM316.9 million to RM16.5 million while his equity interest in Kinsteel is worth only RM21.1 million now compared with RM174.7 million before.

It’s uncertain what roles the two men will play in Perwaja in the future because the Chinese investor is expected to be the largest shareholder and have management control as a condition for injecting fresh capital into the company.

Since last November, Pheng has pared down his stake in Kinsteel from 32.26% to 29.96%. Last December, for the first time since Perwaja was listed, Kinsteel trimmed its holding in the company from 37.34% to 31.25%.

“We had to reduce the burden on Kinsteel because Perwaja’s debt is huge,” Pheng says, adding that Kinsteel is unlikely and unable to inject more capital into Perwaja. But it will not divest any more shares in the steelmaker for the time being.

Nevertheless, Pheng says the consensus is to maintain the listing status of Perwaja and Kinsteel.

Commenting on the significant loss in his wealth, Pheng says, “It is okay.” But he adds that if he is given another chance, he will do things very differently.

“I need to allocate more time to my companies in the future. In this industry, you have to get your hands dirty. You need to actually participate and look after the business,” he says when asked if he will cut back on the time he spends on attending to the affairs of Hua Zong and the Chinese community.

Revival of Kemaman and Gurun plants

Perwaja posted a net loss of RM114 million in the first half ended Dec 31, 2014 (1HFY2015), bringing its accumulated losses to RM1.89 billion. Kinsteel made a net profit of RM83 million in 1HFY2015 due to accounting gains and still has accumulated losses of RM216 million.

However, all is not lost for Pheng and Abu Sahid as the assets under Perwaja and Kinsteel are said to be still valuable.

Before Perwaja’s Kemaman plant was shut down last year, the steel facilities were capable of producing up to 1.5 million tonnes of direct reduced iron (DRI) and 1.3 million tonnes of semi-finished long steel products, such as steel billets, beam blanks and blooms.

The Gurun plant allows Kinsteel to position itself as an integrated steel miller that manufactures upstream, midstream and downstream products. The plant is currently 51%-controlled by Kinsteel while the remaining 49% belongs to Maju Holdings.

The Kemaman plant has to be revived and the Gurun plant revamped, according to Pheng, who knows the restructuring will be painful. “I visited China recently and found that our facilities are not competitive in many aspects. The Chinese firms started to improve their plants many years ago, but we were too worried about profit and loss, which made us neglect the importance of upgrading the facilities.”

Pheng says the plan is to bring in Zhiyuan — a Chinese conglomerate that wants to expand its business in Malaysia — to invest in high technology and produce stainless steel at the Kemaman plant. “Negotiations with Zhiyuan are progressing well. We are hopeful and confident that Perwaja will become a brand new company. This time, with the Chinese firm, I think we are on the right path.”

He points out that stainless steel is a new industry in this country and will be very different from Perwaja’s old business, which incurred high costs and produced low margins. Competition in the stainless steel market is not stiff while demand is high, he adds.

Zhiyuan is expected to upgrade the steel facilities at the Kemaman plant, says Pheng. “We need a professional partner who can bring operational changes to Perwaja. We are still in discussion on the share placement. If Zhiyuan emerges as the largest shareholder, it is actually good for Kinsteel.”

In February this year, Kinsteel approached the Beijing Industrial Designing and Researching Institute of China to undertake a RM200 million revival plan to make its Gurun plant a more profitable steel manufacturer.

Pheng says the Gurun plant might need two new blast furnaces, but he will not elaborate. He adds that the plan is to let the Chinese professional manage the Kemaman plant while Kinsteel focuses on developing the Gurun plant.

“All these years, our biggest problem was that we couldn’t focus on developing either the Kemaman plant or the Gurun plant. We could not manage the plants because of their different locations. This was a mistake,” he admits.

He also urges the government to look into the local steel industry’s problems, notably dumping by the Chinese steel mills. “The steel industry is a core economic area of any country, it is the heart of a nation. We cannot just open our door widely to foreigners. We need to be protected from unfair competition, such as dumping. If the US and China are still protecting their steel industry, so should we.”

Pheng insists that the local steel players are not asking for a bailout, but for tighter enforcement on dumping. Then, the local steel industry can prosper again, he says.

He is also worried that a recent government policy seems to invite Chinese steel millers to this country. Instead of bringing in better technologies to produce higher-grade goods, his concern is that the Chinese players will still make construction-grade steel, leading to competition with the local players.

Note: The Edge Research’s fundamental score reflects a company’s profitability and balance sheet strength, calculated based on historical numbers. The valuation score determines if a stock is attractively valued or not, also based on historical numbers. A score of 3 suggests strong fundamentals and attractive valuations. Visit www.theedgemarkets.com for more details on a company’s financial dashboard.

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly, on April 6 - 12, 2015.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.