This article first appeared in Wealth, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 27, 2021 - January 2, 2022

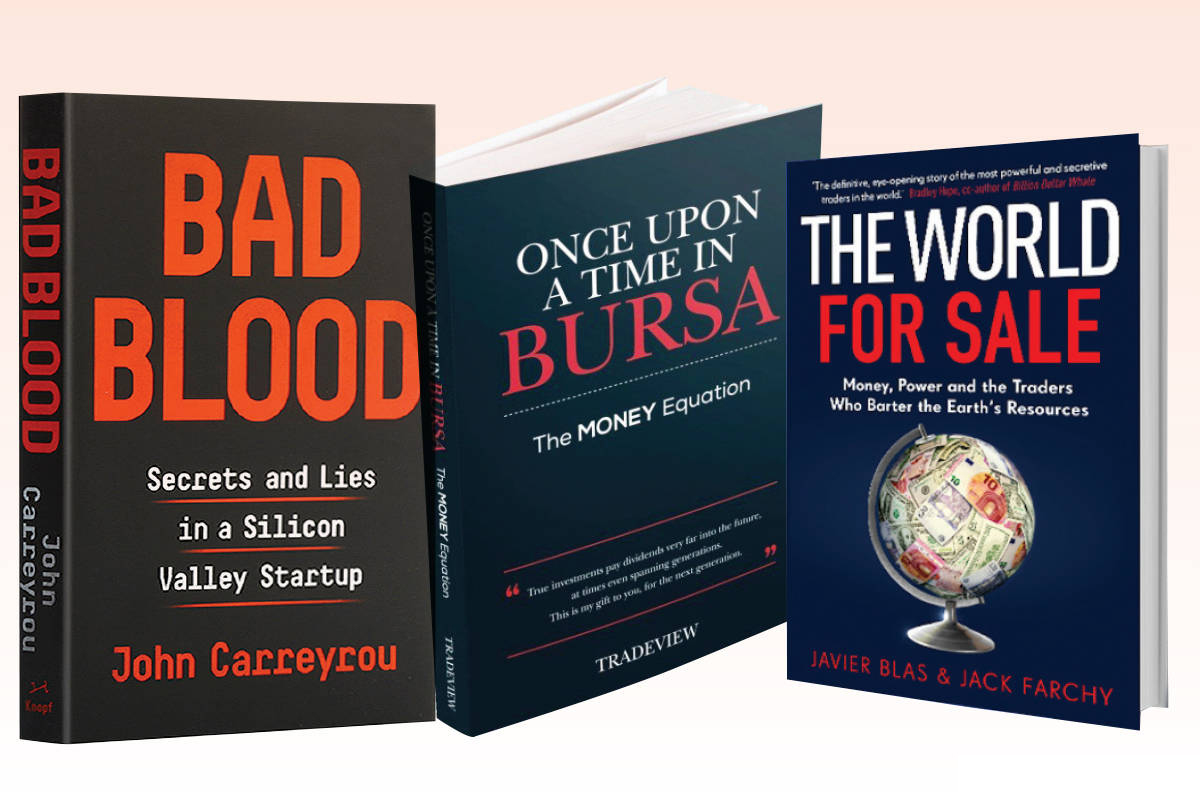

The year ahead may be seen as one of recovery, but many risks and uncertainties still abound. Here, Wealth writers select three books they think will be useful and relevant for readers as 2022 rolls in, together with the challenges it will bring.

Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup

By John Carreyrou

Review by Vanessa Gomes

With the advent of 5G and the promise of more frontier technological innovations, it is easy to get carried away by obscure tech jargon and promises of a better (and easier) future.

This book is a timely and interesting read to help prepare businesses, venture capitalists and local and foreign investors for the innovation that is to come in the next decade or so, as it serves as a good case study of how Silicon Valley start-ups may not be what they seem.

It showcases how the secrets and lies at one such infamous set-up, Theranos, were covered up by empty promises and documentation that may have sounded legit and credible, but in actuality it was using prototypes that were not only unsafe but completely fabricated. Red flags within Theranos and related to its founder Elizabeth Holmes can be seen from the first page of the book, increasing in severity as a complex web of lies was woven within the span of a decade.

The book takes readers back to the early 2000s, when Holmes dropped out of Stanford University to set up Theranos. The company (or rather, Holmes herself) heavily focused on developing a breakthrough health technology device capable of performing rapid blood tests with very small amounts of blood. The device was the brainchild of the Holmes as a response to her fear of needles.

It seemed like a good idea, as there are many people around the world who share Holmes’ fear, but the challenges and shoddy business started when Holmes became obsessed with the size of the device, rather than focusing on its functionality and accuracy. The aim was to have this machine in everyone’s home.

Obsessed may seem like a strong word to describe Holmes’ relationship with Theranos, but a few chapters into the book, one can’t help but wonder what her objective was when she ignored (and subsequently fired) expert personnel who questioned her goals as they were working on developing the prototype. From engineers to lawyers and even a member of the board, Holmes brushed off questions and concerns by removing the people from the company and getting them to sign non-disclosure agreements upon departure.

Holmes kept a lot of elements hidden, especially the research and development process of the prototype (called Edison and later renamed miniLab), and the level of secrecy was a major problem among those who were involved in the project.

The world had no clue that Holmes’ words were empty promises and they looked at her through rose-tinted glasses as she continued to push the miniLab and forge partnerships with more companies. She was celebrated as a biomedical version of Steve Jobs or Bill Gates, a college dropout who could make blood testing as convenient as the iPhone.

The book takes the reader through significant events at Theranos via a specific character’s point of view, seamlessly telling the tales that raised eyebrows at the company. These characters ranged from Richard Fuisz, an American physician, inventor and entrepreneur who knew Holmes in her infancy, to her sorority sisters who were brought on board to work on her prototype.

Holmes undoubtedly had a charismatic personality and was able to charm anyone and convince big companies such as Pfizer and Walmart to come on board, along with a slate of high-profile investors — including Rupert Murdoch, Henry Kissinger and the Walton family (owners of Walmart in the US).

An enigmatic character in this story is Holmes’ ex-boyfriend and former Theranos president Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, who seemed to be the “real” person behind the unfolding scam. For the first half of the book, no one really knows what Balwani’s role was at Theranos and how he had so much power over Holmes.

Balwani, described as “an erratic man-child of limited intellect and even more limited attention span”, adds an element of mystery that makes this book a page-turner.

Bad Blood’s author and acclaimed investigative journalist John Carreyrou, who broke the story of Theranos in 2015, takes readers on a wild ride, presenting evidence of the fraud perpetrated by Holmes and unveiling many dark secrets of Theranos that were not previously known.

At the time of writing, Holmes and Balwani had been charged with two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and nine counts of wire fraud, according to the US Department of Justice’s official website. The court case is ongoing.

Once Upon a Time in Bursa: The MONEY Equation

By Hann Ng

Review by Kuek Ser Kwang Zhe

Value versus growth stocks, which is better? This debate has been swirling around for years. Growth stock investors who put their money in companies with high valuations and earnings potential, though they are not necessarily making profits over the short term, seem to be winning the race in the past two years.

A typical example of a growth stock would be Tesla. Traded at about US$88 per share at the start of 2020, it was priced at US$966 as at Dec 14, representing a whopping increase of 997%!

Yet, it is worth asking the question: Would winners always stay winners? Should investors continue to place more money in growth stocks given a rather different economic environment in 2022, where interest rates are expected to rise on the back of higher inflation? After all, when the market crashes, it is often value stocks, represented by companies with ample cash and little debt, that are most likely to survive better.

For investors, the challenge in 2022 is navigating a volatile and uncertain environment. Perhaps, reading Hann Ng’s Once Upon a Time in Bursa: The MONEY Equation will give them some guidance on fruitful investing.

The main thrust of the book is about the money equation, which represents management, operating cash flow, net cash, earnings and yield. The emphasis on these qualities is similar to investment approaches propagated by other value investors, but it still serves as a good reminder to always have a stake in companies with solid fundamentals and healthy cash flow.

Another good thing about the book is that it does not bog down its readers with mathematical formulas. It uses only one chapter (with 11 pages) to explain the financial ratios most commonly used by investors to value companies, while the rest deals with Ng’s investment philosophy and approaches.

I particularly like the personal and corporate stories. Broken down into three parts, the first comprises corporate stories. In The Tale of Surimi & Family Mart, Ng tells the story of how he, while working as a lawyer in Singapore, read the stories about QL Resources Bhd and its founder Dr Chia Song Kun during his commute to work on the MRT. Born into a middle-class family and eager for success, Chia’s story resonated with Ng. He would end up investing in QL Resources and made a handsome profit a few years down the road.

Other companies featured in the book include TIME Engineering Bhd, Oriental Holdings Bhd, Allianz Malaysia Bhd, Ajinomoto Malaysia Bhd, AEON Credit Service (M) Bhd and more, all of which he invested in later on.

Telling the story of TIME Engineering, Ng mentions Afzal Abdul Rahim’s appointment as CEO and how this key figure successfully turned the company around from five consecutive years of losses by growing its data connectivity business.

Talking about Oriental Holdings, Ng brings up little stories of founder Tan Sri Loh Boon Siew, his character and the family culture that contributed to the company’s success over the decades. The author wanted to highlight that investing is not just about numbers and Excel sheets, but also knowing about the key personalities behind each company.

All too often, many investors and analysts focus on making earnings predictions with mathematical formulas, especially in this technological era of artificial intelligence, big data and machine learning. The importance of good stories is often overlooked.

An example that illustrates the power of storytelling is the book, Poor Economics: The Surprising Truth about Life on Less than $1 a Day. The University of Pennsylvania conducted an experiment recently by showing students two different flyers asking for donations. The first one wrote:

“Food shortage in Malawi is affecting more than three million children; In Zambia, severe rainfall deficits have resulted in a drop of 42% in maize production. As a result, an estimated three million Zambians face hunger, four million Angolans — one third of the population, have been forced to flee their homes...”

Meanwhile, the other flyer said: “Rokia, a seven-year-old from Mali, Africa, is desperately poor and faces the threat of severe hunger or even starvation. Her life will change for the better as a result of your financial gift...”

Unsurprisingly, with just a small personal touch, the second flyer raised more funds from the students than the first.

In his classic investment book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street, Burton Malkiel stresses two things when identifying good companies to invest in: Valuation and stories. The former means buying good companies at an attractive price, while the latter means having a good story to tell and the lessons behind it.

Ng also is not hesitant about naming some companies involved in questionable corporate activities. Some have been widely reported by the media, while others have made dubious announcements to jack up share prices to benefit some shareholders.

The World for Sale – Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources

By Javier Blas and Jack Farchy

Review by Tan Zhai Yun

Oil prices fell below zero for the first time in April 2020 when the Covid-19 pandemic began spreading through the world, and then rose to a three-year high in October 2021 as economies began to open up. Energy prices soared and the impact rippled through global economies.

Who is benefitting from this crisis? Commodity traders, who bought up barrels of oil at low prices when the pandemic first broke out, bought futures to lock in their profits, stored the oil in tankers that they then sold for profit when economies reopened.

This certainly is not the first time that commodity traders have profited from a crisis and likely won’t be the last. In fact, the history of commodity trading since the 1950s has been an exciting tale of adventure, involving charismatic and ambitious characters, the fall and rise of regimes and deals that teeter on the edge of ethical and legal considerations.

Javier Blas and Jack Farchy, who have been covering commodities for Bloomberg News and Financial Times for years, detail this colourful history in this book.

Released in March, The World for Sale – Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources is a riveting read for anyone who is curious about who sets the prices for important commodities such as oil, metals and grains, and how they are moved around the world.

This is an especially relevant read in the current environment, given that high energy prices and inflation are issues that the world is grappling with now, and as the new Covid-19 Omicron variant creates uncertainty in the market, commodity prices are likely to be affected.

More changes are bound to come as concerns about climate change have posed existential questions about commodities such as oil and coal, and as governments have become more serious in cracking down on companies that operate in countries accused of infringing human rights. This book will provide an interesting backdrop to understanding these trends.

The book starts with the story of Ian Taylor, a well-known oil trader, flying into Libya in the midst of its civil war in 2011, to sell fuel to the rebel army. The situation on the ground was lawless and unstable. He flew in on a plane that was at risk of being shot down, accompanied by a Nato drone and bodyguards.

The rebel army desperately needed fuel to continue their assault, but did not have the cash to pay. Taylor took a gamble and sold them fuel in exchange for crude oil from the oilfields that the rebels controlled. This intervention effectively shifted the balance of the war, contributing to the eventual victory of the rebels.

This is just one story of how traders put themselves in extreme situations to buy or sell commodities and in the process, shape the history of countries. These traders hold tremendous power as they influence the flow of important raw materials that fuel vehicles, heat homes and put food on the table.

For instance, in 1972, commodity traders in the US sold almost 20 million tonnes of grain and oilseeds to the Soviet Union. That was equal to almost 30% of the US wheat harvest. As a result, wheat, corn and soybean prices shot up in the US, triggering a severe bout of food inflation. This event became known as the “Great Grain Robbery” and made the US public aware of the power of commodity traders.

The traders rely on their vast personal connections to buy and sell commodities around the world, earning a profit along the way. These connections, however, are oftentimes not acceptable to the public’s standards. But the most profit can be made from dealing with governments that others shun and have no way of exporting or importing commodities by themselves.

For example, when South Africa was sanctioned for its apartheid policies, Iran came to its rescue by supplying it with petroleum. But this ended with the Islamic revolution in 1979. South Africa then turned to commodity traders, who helped it secure oil from Iran, the Soviet Union, Saudi Arabia and Brunei, for a price.

Without these traders, the country’s economy would likely have collapsed earlier than it did, according to the authors.

Meanwhile, things came to a head when a mob kidnapped American diplomats in the US embassy in Tehran in 1979. The US government froze

Iranian assets and imposed a general trade embargo in response. But prominent traders such as Marc Rich continued to help Iran sell its oil. The American public, who were suffering with high gasoline prices then, were furious when they found out that traders were making excessive profits at a time of crisis for the country.

The book is littered with more stories of commodity traders who have played a role in major historical events all over the world, whether it’s the fall of the Soviet Union, the fight for survival of Communist regimes or the rise of China. It also tracked how the industry changed with the introduction of futures and options, which further enabled traders to bet on the direction of the commodity market.

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's App Store and Android's Google Play.